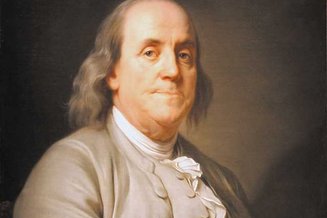

There is no more fascinating character among the Founding Fathers than Benjamin Franklin. An intellectual powerhouse credited with an extraordinary number of inventions and writings, he also was one of the three most pivotal players in the solidifying of the new colonial government, along with George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Historian Walter Isaacson, author of the definitive biography of Franklin, described him as “the most accomplished American of his age and the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become.” It was Franklin who edited the Declaration of Independence as Jefferson wrote it, making significant changes that altered the course of history. (For example, Jefferson had originally written “we hold these truths to be Sacred,” but Franklin altered that to read “self-evident” because, he argued with Jefferson, the new democracy could not be predicated on the old divine right of kings, like the monarchy they had just won freedom from. Thus “self-evident” — coming from the people, not “Sacred,” coming via a kingly conduit to God.)

Franklin was also a statesman, having been Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly and President of Pennsylvania — a position equivalent to governor today.

Franklin was also known as the great communicator among the major players in the colonial era. His joie de vivre and sense of humor ingratiated him with everyone, which is why he became the primary diplomat from the colonies, an ambassador to the French and Prussian courts and U.S. minister to both France and Sweden. In each capacity, he negotiated treaties and opened communication between supporters in Europe and the colonies.

It was in his role as ambassador to France that Franklin also became the nation’s first gay-friendly ambassador, helping a known homosexual escape prosecution and become a pivotal figure in the American Revolution.

Identifying Franklin’s most pivotal role in colonial America is impossible, as there was no arena in which he was not essential, as Isaacson’s biography makes clear. But certainly Franklin’s most significant role in relationship to the American Revolution and the propitious outcome of the Revolutionary War was his delivery of Baron Friedrich von Steuben from the French court at Paris to George Washington at Valley Forge.

Washington himself felt that von Steuben’s military strategies were vital to his success in the war; von Steuben’s expertise was so stellar that his military manual, “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States,” became the fundamental guide for the Continental Army and remained in active use through the War of 1812, being published in over 70 editions.

Had it not been for Franklin, however, Washington would never have gotten his military strategist and von Steuben may have spent the remainder of his life in prison somewhere in Europe.

At the lead-in of the Revolution, Franklin was a mediator between the French and the colonists in negotiating the support of France against the British. It was during this period of intense political complexity and foment that von Steuben was first approached.

Franklin knew of von Steuben’s homosexual encounters, but didn’t consider them relevant to a position in Washington’s Continental Army. In June 1777, rumors of homosexual activity had forced von Steuben to resign his role as chamberlain to Prince Joseph Friedrich Wilhelm of Hohenzollern-Hechige, in southern Germany. Von Steuben traveled to Paris — some say fled — seeking a position in the French army or the Continental Army, through American military representatives like Franklin.

Washington had sought a military strategist, but had insisted on someone who spoke fluent English. Von Steuben spoke German and French and very little English, so Franklin was initially leary of recommending him to Washington.

But — and this is where Franklin’s gay-friendly attitude is most obvious — Franklin had empathy for von Steuben’s increasingly problematic circumstances and decided to write letters of recommendation to Washington and bring von Steuben to America. These letters of recommendation came immediately following a crisis for von Steuben.

Having first rejected a non-paid position offered by Franklin, von Steuben found himself in danger of being prosecuted. A letter dated Aug. 13, 1777 to the Prince, for whom von Steuben had been chamberlain, threatened von Steuben:

“It has come to me from different sources that M. de Steuben is accused of having taken familiarities with young boys which the laws forbid and punish severely. I have even been informed that that is the reason why M. de Steuben was obliged to leave Hechingen and that the clergy of your country intend to prosecute him by law as soon as he may establish himself anywhere.”

Franklin and von Steuben met again and Franklin expanded and revised von Steuben’s résumé to make it more attractive to Washington, wrote letters of recommendation for von Steuben and arranged for his passage to Pennsylvania.

Von Steuben arrived at Valley Forge in February 1778 with his 17-year-old French lover, Pierre Etienne Duponceau.

The rest — thanks to Franklin — is history.

It wasn’t solely as ambassador that Franklin made gay-friendly history in early America. In his role as America’s printer extraordinaire, Franklin had been responsible for facilitating the printing of the first male same-sex love story in North America through his friendship with and mentoring of French printer Fleury Mesplet.

Franklin had befriended Mesplet after meeting him in London during one of his many sorties abroad. There are different versions of how Mesplet arrived in Philadelphia, but he was both a revolutionary and a printer, and his friendship with Franklin deepened during his time in Philadelphia. He then moved to Montréal with the American Army in 1775 as a printer for the colonial Confederation. But when he failed to convince Quebec to engage in the American Revolution, he was imprisoned as the British Crown retaliated, charging him with sedition.

Mesplet would become one of the most historically significant printers in Canada. In 1785, he founded the Montréal Gazette, now the oldest continuing newspaper in Canada. For LGBT historians, however, Mesplet is famous for printing the first book in Montréal, which was also the first homoerotic publication in North America.

In 1776, Mesplet, whose friendship with Franklin bolstered his revolutionary fervor as a printer, bookseller and writer, published the play “Jonathas et David,” or “Le Triomphe de l’Amitie.” The play details the homoerotic relationship between Jonathan and David in the Old Testament — a depiction still considered controversial today, 235 years after Mesplet’s publication.

Franklin was known as a sexual profligate — he spent little time with his common-law wife, Deborah Read, once he began to travel abroad, and was known for his many dalliances with women and writings on the topic of womanizing. He had one illegitimate son whom he recognized and may have had others. One presumes Franklin’s own expansive sexual appetite allowed him not just tolerance but empathy with regard to von Steuben — and also kept him from suggesting to Mesplet that homoerotic plays might not be the very first thing to publish in his new Canadian home, when he was already under suspicion for his political views.

Franklin’s life was mesmerizingly rich and the breadth of his contributions to America incalculable. Added to that, now, can be his own significant contributions to LGBT history in North America.

Victoria Brownworth is an award-winning journalist and syndicated columnist. She is the author and editor of nearly 30 books, including the award-winning “Too Queer: Essays from a Radical Life” and “Coming Out of Cancer: Writings from the Lesbian Cancer Epidemic.” In 2010, she founded Tiny Satchel Press, an independent publisher of books for LGBT youth and youth of color.