In this day and age, it’s hard to picture anyone surviving in New York City on $400 a month. Even the homeless can’t pull off that feat. But thanks to Edmund White, we don’t have to imagine.

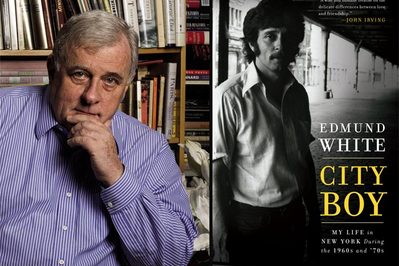

The acclaimed 69-year-old author and critic transports readers to Manhattan during a tumultuous and vibrant time in its history in his latest memoir, “City Boy: My Life in New York During the 1960s and ’70s.”

Fans of his other memoirs, like 2005’s “My Lives” and 2001’s “The Flâneur,” or his autobiographical fictions “A Boy’s Own Story” and “The Farewell Symphony,” should delight in his equally candid and descriptive new book.

White said he doesn’t have a preference between fiction and nonfiction when it comes to writing.

“I write all these different categories of things that kind of overlap,” he said. “I think in writing a real autobiography like ‘City Boy’ or ‘My Lives,’ the pleasure is in imitation. In other words, you’re trying to imitate something that really happened and you’re trying to get it right. You try to check your memories with other people’s and with the public record and history. But it’s not just external facts that you’re trying to capture. You’re trying to capture the real feelings you had at the time and not rewrite them in the light of what you feel now. All that is very different from writing fiction, where the primary purpose is to create a beautiful object that will have nice proportions and have a satisfying sense of form, and that will imitate life as we know it. They are very different enterprises.”

White’s latest literary enterprise starts off with him ditching graduate school to follow his then-boyfriend to the Big Apple. After landing a job as a journalist, White, who had grown up in Chicago and gone to college in Michigan, soon discovered New York had a far more visible gay culture than any place he had seen before.

“It was delightfully different,” he said. “The very first night I got to New York was July 19, 1962. The next night a friend of mine took me to a gay restaurant. I had never heard of such a thing. I had been to a gay bar, but the idea that gays would want to sit around and eat with each other and not just cruise and have sex with others seemed like a totally novel idea. I loved that idea of gay culture as opposed to gay sex. That was a brand-new idea to me.”

Readers quickly discover the New York City of that era, while teeming with culture, wasn’t the outrageously expensive and sanitized tourist metropolis most know it to be today.

“It’s a lot safer now than it used to be and it’s a lot less dowdy than it used to be,” White said. “But it is also less exciting and less creative. I suppose you win some and you lose some. It really was dangerous in the late 1960s and throughout the ’70s. My apartment was burgled three times and I was held up on the street in broad daylight in front of other people by a robber with a gun. Things like that would happen. Gays would be beat up all the time by kids who lived in the projects.”

And those were the good ol’ days?

White said that despite all of the recent changes New York City has undergone, there are still some extant pieces of the New York he wrote about in “City Boy” — even if their property values have skyrocketed.

“There are places that survived. Julius, the gay bar, has survived this whole time. It’s in the West Village. I suppose a lot of the streets in the West Village, like Charles Street or Bank Street, haven’t changed that much. They have been tarted up a bit. That used to be a fairly average area in terms of real-estate value. Now it’s the most expensive area of New York.”

“City Boy” is just as much an emotional picture of the times as it is physical. In the book, White recalls not feeling very moved in the early 1960s when a friend brought up the subject of patriotism; he didn’t feel that, as a gay man, he had a voice in the country’s political structure.

“There’s a lot more power now,” he said. “For one thing, so many more people are out than they used to be. Even though we were a very small portion of the population, we’re a fairly well-organized minority group. I think that in the disputes over Proposition 8 in California, you can see that even though we didn’t win the first time around, we might well win this time. There have been quite a few elected gay officials on a local and national level. There are gay spokespeople in every domain. We were entirely invisible when I was coming out in the ’50s and ’60s. You could watch TV for a year and never hear anything about homosexuality mentioned. Now it’s a real aspect of American life.”

White said he was present at the Stonewall riots, the event in 1969 that sparked the gay-rights movement. He admits that, at the time, he didn’t know or understand how big and far reaching that moment would be.

“On some dim level, I did recognize that something significant had happened because something had happened to me, inside me, in my own feelings,” he said. “I, at that time, was in my hundredth year in therapy trying to go straight. And yet there was something in me that was very exhilarated by this sign of gay defiance and gay resistance to authority. We had never had anything like that before. My first instinct was to try to get everybody to be quiet and go home. I was this awful middle-class prig. But in spite of myself, I found myself really getting into it and really enjoying the rebellion of it all. It wasn’t one night. It went on for a whole weekend and I came back for the next installment.”

The 1970s are also vividly recounted by White, who spent the “Me Decade” surrounded by the city’s growing gay scene of artists and writers, with all the requisite famous names and cultural icons.

But it all wasn’t meant to last. White move to France in 1983 and, by the time he returned in 1990, AIDS had devastated the city’s gay arts scene. White, who is HIV-positive, said France handled the crisis differently.

“In America, I was a member of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis,” he recalled. “I was one of the six founders of it, which started in 1981. We were so ghettoized that we really thought small. When we realized it was this terrible disease, the most we could think to do was to have a fundraiser at a disco. It was really quite contemptible how small we thought, and it was a sign of how alienated we were from the nation and the community that we didn’t turn to the government and ask for help on a large scale. In France in 1985, I sat in on the first meetings of the gay organization that was just beginning, AIDES, and there that group turned immediately to the Minister of Health and got a national budget and a national policy.”

White added that, though it moved on a larger scale, France’s tactic was not necessarily more effective than New York’s.

“The French were very reluctant to name the at-risk groups because they were worried about backlash against gays,” he said. “It meant that a lot of gays were under-worried or under-alarmed and that they didn’t pay attention to safe-sex practices. Nor was there very good information about it. In America, we were very scared and made a lot of fuss. We had fairly good results in certain communities but not all. For instance, bisexual men weren’t really reached. A lot of working-class people were not really reached. I certainly got a different perspective in France: I can certainly see good points and bad points on each side.”

Given the administration at the time, White doubts help would have been forthcoming from the government.

“It’s true that Reagan almost never mentioned the word AIDS while he was in power. But the Secretary of Health was a liberal guy with some very good medical notions about how to handle the disease. Reagan was so much opposed to even acknowledging the disease existed that probably reaching out to the government wouldn’t have helped.”

Meanwhile, White knows many who read “City Boy” are bound to be children of the Reagan era or later and have no first-hand knowledge of the 1960s or ’70s. But he hopes their interest in the era will make the book an enjoyable read.

“It’s always fun to read about a glamorous earlier period that was really creative, where people were living on the cheap and by their wits,” he said. “All that is fun. When I was growing up, the model was the 1920s and we were all enthralled. Now I think young people are very interested in the 1970s as a kind of model for what it would be like to live free and live on the cheap. Of course, it’s almost impossible to live in a big city in America inexpensively. Then it was possible, and a lot of it does come down to economics. But still, it’s kind of amusing to read about an artistic world that was very vital but very small at that time.”

Edmund White hosts a reading at 5:30 p.m. Oct. 8 at Giovanni’s Room, 345 S. 12th St. For more information, visit www.edmundwhite.com or call (215) 923-2960.

Larry Nicholscan be reached at [email protected].