The first gay disco, Studio One in Los Angeles, was a safe space for the gay community from 1974-1993. The West Hollywood club is now the subject of the affectionate documentary, “Studio One Forever,” available on digital Jan. 6.

Director Marc Saltarelli assembles a handful of employees and patrons, as well as celebrities who performed there or at The Backlot, a venue that connected to the disco. The building was slated to be demolished in 2018, and this film provides an oral and visual history of the club as the local board determines its fate. A handful of “survivors” of Studio One, including comedy legend, Bruce Vilanch, return to the club to recall its glory days.

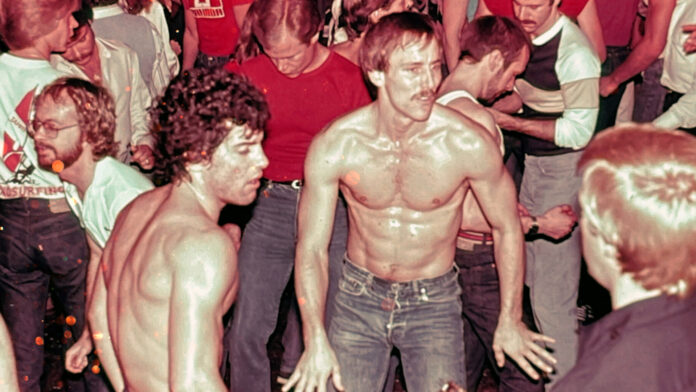

The anecdotes and images shine as Saltarelli interviews a variety of individuals, including Michael Koth, a former bartender at Studio One, who shares captivating stories about its patrons and co-founder, Scott Forbes. He dispels the rumors that Forbes used to bury the money he made from the club. Other interviewees, such as John Duran, a West Hollywood City Councilman, talk about finding himself and his tribe in the disco. Studio One allowed gay men to be their true selves only a few years after the era where two men touching in public was considered a crime. Several patrons who frequented the club lived double lives — being open and happy within the confines of the disco, and closeted about their personal life outside the club as there were concerns about being outed or openly gay back in Studio One’s heyday.

The club was a model for New York’s Studio 54, as it promoted “sex, drugs, and rock and roll,” as well as celebrities. Studio One hosted the “Tommy” premiere afterparty, and footage of Ann-Margaret, Elton John and Diana Ross all playing pinball is fabulous. Chita Rivera, who is interviewed in the film, discusses performing her act at the Backlot, as do singers Roslyn Kind (Barbra Streisand’s sister) and Julie Budd.

Celebrities such as Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Rock Hudson, Lucille Ball and others all went to The Backlot; they were curious to attend events and also appreciated a kind of anonymity the club gave them. The legendary Bette Davis introduced Geraldine Fitzgerald’s act at the Backlot, and Joan Rivers hosted an AIDS benefit at the club, which generated threats. Her daughter Melissa, who appears in the film, describes having to go to school with bodyguards.

Studio One was also used in a music video by Sam Harris, who won “Star Search” back in 1983, and the venue has the dubious distinction of being featured in the camp classic “Can’t Stop the Music,” starring the Village People. Felipe Rose (Indian in the band) frequented the club and reminisces about his experiences in the film which is fun.

All the love is genuine and heartfelt, but Saltarelli tries to cram too much into 95 minutes. One segment of the film emphasizes Scott Forbes coordinating a Studio One, or “gay day” at nearby Disneyland — even though the organizers were concerned about identifying it as such. Photographs of men holding hands or kissing on the rides are gratifying to see.

However, the film only briefly touches on the charges of racial and sexual discrimination that Studio One faced. Although two of its co-owners, Ernie Caruthers and Dino Lopez, were people of color, Forbes had policies that restricted Black people and women, who often had to show multiple forms of ID to enter. Several interviewees acknowledge the issue, but it feels glossed over.

Also, as disco fell out of favor, and the AIDS epidemic began, the club experienced troubled times. The emotional stories of grief and loss recounted in the film are, as expected, heartbreaking. But there are other emotional accounts by interviewees that illustrate gay men’s experiences during the era. Two potential clubgoers were victims of homophobia outside Studio One. The episode resulted in the tragic and senseless death of one man. And Studio One bartender Michael Koth discusses how he slept on the stairs of the club while homeless and battling addiction. A sidebar on club patrons Lance and Leo Ford, who co-starred in a popular adult film, mentions Leo Ford’s brief relationship with Divine, as well as Lance’s death from AIDS. These stories are related to Studio One but feel tangential. Likewise, a credit sequence featuring Lance Bass talking about his contemporary club in Los Angeles, seems both unnecessary and crudely tacked on.

The film is best when it focuses on the history of the club. A sequence where Vilanch and others visit One Archives at the USC Libraries, is interesting as flyers and other club artifacts are unpacked and discussed. Likewise, when a young queer woman, Natalie Garcia, discovers a cache of slides of images from Studio One, she creates narratives of the men in the photos and asks Michael Koth about the clubgoers. Even a bit about patron Paulo Murillo gushing about Jimmy, one of the go-go boys who performed at Studio One, is amusing. And when Saltarelli reveals the fate of the space at the end of the film, it seems like a fitting ending for a celebrated venue.

“Studio One Forever” may be best appreciated by those who knew or have been to the club — as the interviewees’ trips down memory lane attest. But this documentary also provides an engaging history for viewers curious about gay history.