“Peace is not something you wish for, it is something you make, something you are, something you do and something you give away.” ― Robert Fulghum

It can be challenging to embrace the peace on earth and goodwill of the season when it feels like disdain and disrespect are becoming normalized across the country.

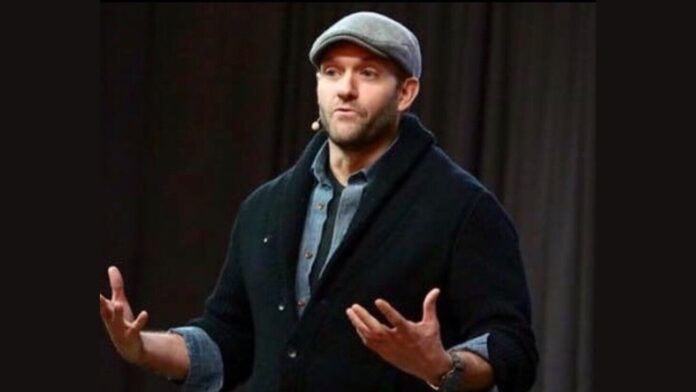

One person working to combat the divisiveness and anger is this week’s Portrait, Sean Harvey. Harvey is the senior strategic advisor and founder of the Warrior Compassion Institute, an organization whose mission is to work with men to dismantle hate, bridge polarization, and humanize hypermasculine systems, organizations and communities.

A noted author and sought-after speaker, Harvey was voted one of the top 15 coaches in Philadelphia by Influence Digest and received the Saul A. Silverman 2021 Award for Conflict Resolution and Healing from the International Organization Development Association. His book, “Warrior Compassion: Unleashing the Healing Power of Men,” offers a roadmap for men’s soul healing as a catalyst for change.

Some responses from this conversation have been edited for length or clarity.

Tell me where you’re from.

I’m from a small farm town of about 1,500 that’s basically west of Toledo, Ohio. And then when I was seven, I moved to the suburbs of Dayton, Ohio. So I went from rural to suburban.

What are some favorite memories from life in the country?

We had an acre in the backyard, and I remember riding in a wagon with my grandfather down this huge hill, a lot of pussy-willow trees, and living across the street from the cemetery. We had three cats and my godparents were farmers in the town over. And my father was a long-distance truck driver, and he would take me on the road with him. He hauled sailboats for most of my life.

That’s pretty cool. Did your grandfather live with you or near you?

No, he lived in Detroit but he would come up and visit. He was very playful.

Do you have any siblings?

No, I’m an only child.

What did mom do?

My mom didn’t work back then. My dad wouldn’t let her. He left us when I was young. Actually he divorced her and before he died, I asked him, “Why’d you leave us?” And he was like, “Because your mama, you know, she started going to college, started having ideas. She started thinking for herself, and I couldn’t deal, so I left.” At least it was honest. That was in the 1970s, so that was typical at the time.

Yeah, things were changing, and I’m sure that probably upset a lot of people. How would your mom describe you as a kid?

Curious, playful, stubborn. She would always say that I always found and followed my own path.

A favorite family memory or tradition?

My mom would take me on a backpack and take me hiking in the woods in Toledo, and also being on the road with my dad. He would be smoking a cigar and talking on the CB, while I was riding in the passenger seat, and he would have these really deep, profound conversations. Another is with my grandfather. I write about this in my book. Every night before bed when I was in Detroit, my grandfather would pull up a cot next to his side of the bed for me to sleep on and he would tell me the stories of Little Red Chief. He was a Cherokee warrior, and I’m part Cherokee. Red Chief was a young boy being developed by the chief and the warriors who were teaching him how to be a compassionate warrior.

What were some of the extracurricular things that you participated in at school?

Well, I was a high-school cheerleader. I also started the first gay and lesbian youth group for the city of Dayton, Ohio when I was 16. I was a teen crisis counselor. I was in the Honor Society. I was also in an arts and culture group, but actually, I was pretty much a loner. I mostly just kept to myself.

Why was that?

I mean, being a queer kid in the 1980s, in suburban, redneck Ohio is not the easiest thing. It wasn’t like I really fit in. So I just created my own thing. I created YouthQuest, which still exists today and now serves 80 youth across the entire Southwest Ohio.

That’s excellent. Tell me a little bit about your coming-out journey.

I had a friend of mine who kind of pulled me out. When I told my mom, she said [with an accent], “Ah, you have kids. Sometimes they’re gay, sometimes they’re straight. So, you gay. Get out my face.” And that was it. But then I told her that I didn’t like chocolate. And she was like, “How can you be my son! My child? How could this happen? Who are you?”

I hear your mother. My nephew came out to me, and I was his biggest cheerleader. But then he told me that he didn’t like cheese. I was like, “What kind of monster doesn’t like cheese?” But back to you, tell me a little bit about what started you on your path to the work that you do now.

I left Wall Street. I was a management consultant, and I’d gotten to the point where I was just done. I was the vice president, and head of the talent consulting division of a firm in New York and our clients were media Wall Street firms, but I’d had enough of that environment and I resigned on my 40th birthday. It was my birthday present to me.

I left Wall Street and went to work for Eileen Fisher, the women’s fashion company. I went on an eight-month interview process. I really wanted to work with them because they were innovative and I always thought it’d be cool to work in fashion. I was very type A, had a great resume, and I went on a five-year journey at Eileen Fisher. On my first day on the job, my two bosses sat me down and said, “We just want to let you know that you have proven yourself in the interview process. Now we want you to stop proving yourself and learn how to be who you actually are. You’ve shown us your polish but we hired you for your heart. We don’t care about your accomplishments. We want to know who you are.” I experienced so many things there, including when they sent me to an artist commune in Canada for five months to learn how to incorporate the arts in a creative facilitation.

Wow, that’s pretty incredible.

Yes, I left Wall Street to never work with men again. But going to Eileen Fisher and the commune I got the spiritual calling to do the work I do now. I was given the message that I was meant to work with men, to address the issues that don’t get talked about. So that led me to seminary. I went to seminary in New York and became an interfaith minister for the sole reason of doing soul healing work with men.

I knew, as a systems thinker, as an organization development practitioner, if we were going to create true societal systems change — and not just replace crumbling, oppressive systems with outdated models — we had to reimagine them from deeper consciousness and collective wisdom. And the Achilles heel to all of this work would be white men in power, holding on to power from wounding, and not healing. We need to heal those men to start creating a movement of societal change.

So I finished seminary, and two days after saying my vows, through a buddy of mine, I was contacted by the chief of police of the Asheville Police Department. He said, “If you’re a member of the community and you want to be part of our police-reform efforts, email me directly.” I responded, “My best friend in London, who’s mixed race, will visit me in New York, but won’t visit me in Asheville because he’s afraid of being murdered by your police.” This was June 2020, after George Floyd. So all my friend saw was that in America, our officers killed Black men, right? So that led to a one-on-one with the chief of police. He had two asks. One — can you help deepen the level of compassion among my officers? And two — can you create conversations that humanize officers and community members for new relationships going forward. I said yes.

That led to me meeting FBI agents and military officers and police officers, and we formed what we called Project Compassion, which was a national initiative to deepen compassion in police departments, federal law enforcement and military security forces. I started meeting white nationalists and hate-group extremists, and I started realizing that I have a way with conservatives. And then I met my ex-boyfriend, an ultra-conservative MAGA conspiracy theorist, and that relationship really taught me how to love the person, even if I hate the views.

Since then, I have started working more and more with hate-group extremists and talking to my spiritual guides to bring love to hate. Just last week, I met with a founder of the neo-Nazi movement in America. He left the movement and is now pulling guys out. We compared notes on our de-radicalization practices. He’s been doing this work for 20 years, and it was kind of a passing of the baton. Working with leaders to support men, and also to identify men that might be vulnerable to radicalized ideology.

I would imagine sometimes it can be scary going into some of these spaces or speaking to some of these people.

No, for a couple of reasons. I was just talking about this earlier today. I’ve made peace with the fact that I could get killed doing this work, and I made peace with the fact that this work is worth dying for, because it will save lives by doing it. So I made peace with death in this work a long time ago, and I don’t really walk in fear. I also know that most of these guys find me non-threatening and feel safe opening up with me, I think partly because I have a certain privilege as a white, gay, cis man with a particular look or demeanor and masculine energy. I’m able to walk into spaces a lot of other people can’t.

What’s one of the most surprising responses you’ve received and what’s one of the most fulfilling ones?

I think one of the most interesting was working with a gay dude who wanted to be the face of the white power movement, and I think what surprises me is that I can do this work so effortlessly, and somehow know what to say and how to say it, and understand the complexity of it. It’s always interesting to me to be able to hold their hate and push back love, and then to see their reactions when they can start to see things from a different perspective. As a minister, I’m able to speak with evangelical Christians.

What’s coming up on the agenda?

I’m starting my Bridging Divides incubator. With a small group of folks and change-makers from across the globe, we want to determine the models needed that haven’t been thought of. What are the practices that haven’t been created for the level of hate and polarization we are currently experiencing in society? How do we amplify the power of compassion as a tool for building bridges across cultural, political and ideological divides?

You’ve been doing this for a little bit now. It feels like the level of hate in this country, in the world, but especially in the U.S. right now is heightening to crazy levels. What’s your perspective on that?

We are deeply polarized and not able to really see each other. And I think there’s a political aspect. But when I look at it globally, probably our most polarized divide is gender. And I think we’re at a point where we’re just not willing to engage with people that hold different ideas or different perspectives from our own. We’re just not able to get past if we don’t believe our values are in sync, and so the more we stick with our like-minded groups, and the more we “other” those who don’t hold our beliefs, we discount or diminish or close them out. We do it on the left and the right and I think the power players like it that way. Because the more divided we are, the easier it is to manipulate people.

For sure.

When I do this work, the reality is that people want to connect. I often say that the key to what I call the bridging mindset is the four C’s — curiosity, compassion, courage and community. Where I’m most successful with the people that I reach is by having open-hearted, non-judgmental curiosity.

Right on. So let’s move on to some random questions. What historical event do you wish you had witnessed?

My grandfather was in World War II under General Patton. I’m fascinated by that era, I’m fascinated by that war. I’m fascinated by a combination of what happened in Europe, what happened in the Holocaust, how it could have happened.

What stuff do you do for fun?

I’m learning how to white water kayak. I am a big animal person. I love to dance, I was just in New York this weekend for a dance party. I’m a foodie, and I like to just go. I love both the beach and the mountains. When I lived in North Carolina, I loved going on the Blue Ridge Parkway and getting lost in the mountains. I think if I were to do it over again, I either would have been a dancer or a race car driver.

You’re a foodie. Who are three people you’d like to invite for dinner?

I would want my father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather on my father’s side. I would really love to have dinner and talk about things to do the generational healing of our ancestors. My grandfather’s half Cherokee, half Irish and what I’ve inherited from him and my father is the art of storytelling. I’d probably want to go whitewater rafting with them. And then sit around the fire at a campground telling stories.

Oddest job?

I was a valet at a fondue restaurant. That’s where I learned how to drive an automatic stick shift. It was on someone’s BMW. And I used to be a rabbit educator. I would prep people for their first bunny rabbits.

Favorite type of clothing?

Hoodies and shorts. That’s my favorite outfit.

You’re going the Fetterman way.

Yeah, I actually want to reach out to him. I’m on the regular briefing calls with Homeland Security, so we get the updates on domestic terrorism, hate activity and extremist activity across the Commonwealth of PA. It’s interesting to think about connecting with both local and state officials on how to address hate across the state.

A lot of people don’t realize that Pennsylvania has one of the largest numbers of hate groups in the country, right?

Yes, number-one is California, number-two is Florida, and then number-three is Pennsylvania.

What’s a pet peeve?

When people have such a need to be right that the need supersedes the desire to be curious.

An interesting fact…

In Asheville, I was renting a room from a shaman, who had a chapel in the backyard. This is on Cherokee land and the chapel was built for families of gay men who died of AIDS in the ’80s and ’90s, who didn’t have a house of worship because down in the South, they wouldn’t allow funerals for gay men. So this was built for the families of gay men who died of AIDS. And that’s where I gave my TED Talk on Compassion Makes the Warrior.

Beautiful.