It’s not news that book censorship has become a major point of contention for libraries across the U.S., both for public libraries and especially for school libraries. It’s an unfortunate fact that, according to reports by PEN America, which keeps statistics on this issue, the top three states where the effort to ban books from school libraries are most prevalent are, in descending order, Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania.

It should also come as no surprise that the books most targeted for banning by conservatives are those featuring LGBTQ+ characters or themes, racial and social justice and other political topics, BIPOC characters or themes, and diverse or representative materials.

However, many major public libraries have been devising programs geared to fighting the rising tide of censorship, particularly for students, whose school libraries are especially vulnerable to conservative political pressure.

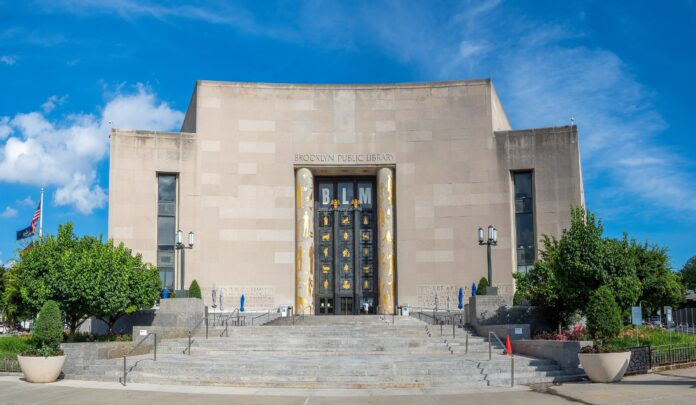

New York’s Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) has been among the most active library systems in addressing the book censorship crisis. In 2022, BPL launched its Books Unbanned program. Among the many pieces of the program is its extension of digital library cards (eCards) to anyone between the ages of 13 and 21 in the U.S. This grants young people access to its vast digital collection, including the kinds of books that are being banned nationwide.

Since its inception, BPL’s program has extended to include several other libraries. According to Fritzi Bodenheimer, BPL’s Press Officer, “Boston, Seattle, LA County and San Diego have joined Books Unbanned with similar programs of their own.”

The program does not currently include the Free Library of Philadelphia. However, according to Mark Graham, communications director for the Free Library, the Books Unbanned program is being looked at. In an email to PGN, Graham wrote, “The Free Library staff will consider programs such as the Brooklyn Public Library’s Books Unbanned. Several branches have events that are aligned — and we all join in promoting the freedom to read.”

Graham went on to explain the Free Library’s commitment to accessibility for marginalized communities.

“The [Mayor] Parker Administration and the City of Philadelphia’s Free Library take the freedom to read very seriously,” Graham wrote. “It’s a motivating principle behind all we do. For instance, many of our neighborhood branches have been celebrating challenged and banned books during the recent national Banned Book Week. We put our principles into practice every day through our commitment to inclusiveness, diversity, equity and accessibility; by hosting quality programs by and for LGBTQIA+ and communities of color (who face the most book challenges in the US); and by implementing our material selection policy that guides the collection in our libraries.”

As part of the Books Unbanned program, BPL asked applicants to share why they wished to get a card. In the first year of the program, teens who wanted a card would email and receive an auto response which allowed them to respond with their stories and experiences. The request for response was voluntary, and teens indicated whether or not those stories could be shared publicly, with identifying information removed in order to protect their privacy.

The response forms also gathered data on a number of subjects, including where these responses were coming from, why the teen wanted an eCard, the barriers to access faced by the teen, and other data points.

Thousands of teens have responded with their stories since the program’s inception. Perhaps the most interesting data point is why the teens wanted or needed an eCard. In descending order, teens cited the following reasons for requesting an eCard:

• Rural/“small town”

• Religious/conservative community

• Homeschooled/online school

• Low income

• Living abroad/traveling

• Not out/“closeted”

• Harassment/bullying/discrimination

• Military family

• Reservation/US territory resident

• Single parent

• Hospitalized or under other institutional confinement or care

• Unhoused/unstable housing

This data shows that, while censorship and homophobia are major factors, they’re not the only barriers to access teens face, particularly those in small or rural communities, or who are in unstable living situations. This only goes to show the magnitude of the problem of making sure that students get access to books and materials they need to properly prepare them for life.

A careful examination of the data can also provide information where things are going well—for instance, Philadelphia, which came in second on the list of cities in the proportion of applicants offering stories. A closer analysis of the data showed this was likely not because of any problem with access in Philadelphia’s extensive public library system.

According to Bodenheimer, “Our team looked at our full collection of stories and then filtered by Philadelphia. The vast majority were submitted in a short time span — over a few days in September 2022 — and a lot of the stories are very similar, almost verbatim. So we think it was likely a class assignment where everyone had copied and pasted the same thing. This makes sense to us because Philadelphia is not a city where we would expect significant challenges to books.”

Further details were not forthcoming in order to protect the privacy of the students involved.

However, Pennsylvania as a whole came in fourth on the list of teen applicants who responded with stories, after Florida, Texas and California. This suggests that teens throughout PA face many of the listed obstacles to accessibility.

Teens nationwide are taking advantage of the program. According to Bodenheimer, “Our Books Unbanned program [began] April 2022. Since that time, we have distributed eCards to over 9,000 teens in all fifty states. The card gives them access to our entire digital collection of approximately half a million items. Since the program launched, teens with the card have checked out nearly 300,000 items.”