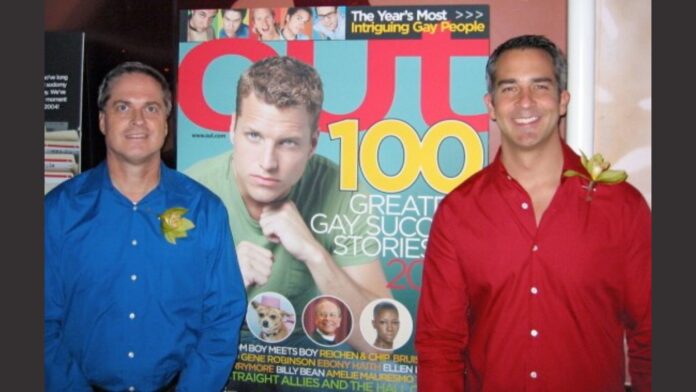

“The evolution of a company’s policies and branding and reputation is a lifelong work-in-progress,” said Bob Witeck, a pioneering LGBTQ+ business leader and communications strategist.

Concepts like DEI are mainstream today, and advertising to LGBTQ+ customers is commonplace — but neither were the norm thirty years ago. Witeck is one of the trailblazers who supported some of the first major companies in the early ’90s to openly welcome and affirm LGBTQ+ people — both as customers and as integral members of the workforce.

“We want the companies to want to do it because they know it’s aligned with who they are — it’s aligned with what they try to do in the world,” he said. “Because they want to make people feel good, but also because they want to make people empowered.”

Witeck noted that “vice-driven” businesses — like tobacco and alcohol — and some apparel companies marketed in LGBTQ+ bars and publications long before business leaders in other industries were ready to take that risk.

Witeck said they kept a distance due to the “usual anxieties” — fearing backlash. They worried that advertising to LGBTQ+ customers or supporting LGBTQ+ causes might alienate existing cis-het customer bases.

But in 1993, a PR disaster forced one company — American Airlines — to reckon with their values, and the way Witeck helped the airline handle those blunders shaped modern history well beyond the marketplace.

First, an employee cited a group of onboard gay men as a reason to change all linens for the next flight. The memo describing the request was leaked to the news, prompting a swift apology. Witeck said company leaders recognized that they might have LGBTQ+ employees and customers to protect and amended the airline’s nondiscrimination policy to include sexual orientation as a protected class as a result. They also became the first Fortune 100 company to develop an LGBTQ+ specific marketing team.

But just a few months later, a visibly frail passenger living with a late-stage illness related to HIV was forcibly removed from an American Airlines flight after he attempted to self-administer IV medication. Threats of protests and boycotts loomed.

Witeck and his team worked with the airline to transform the company’s culture from the inside out and encouraged leaders to respond to the public with authenticity. He and his team of LGBTQ+ colleagues developed a plan to help American Airlines embrace DEI tenants not just as a marketing gimmick but as a core value.

The company took a multi-pronged approach to next steps — communicating with transparency, implementing new policies, training and educating employees, and supporting HIV/AIDS advocacy efforts and broader LGBTQ+ activism.

“They got it,” Witeck said about the airline’s commitment to “heavier lifting and the more substantive work” of cultivating new cultural norms — in contrast with simply “checking boxes,” which might save face but fail to address the true needs and expectations of LGBTQ+ people.

That same year, Witeck worked with the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) to develop a prototype that would evolve into the modern Corporate Equality Index (CEI) — a benchmarking tool that rates businesses based on social responsibility, internal policies and employee benefits with a specific focus on LGBTQ+ inclusion.

“Our purpose here is not to sell more cars to gay people or more toothpaste or more diapers,” he said. “But to make sure gay people are fully engaged and leading in every sense.”

The CEI incentivizes companies to think beyond marketing and token gestures to implement more meaningful changes to corporate structures. It’s also a tangible way for LGBTQ+ people to measure how committed specific companies are to queer rights.

“It’s not just Pride Month or Gay History Month, doing sponsorships — but having real relationships with nonprofits, taking on some of the causes that matter to us, making moves on trans healthcare and marriage and job discrimination,” Witeck explained.

American Airlines became one of the first major corporations to sponsor the Human Rights Campaign — helping to set a new standard in corporate America for the role businesses could play in advancing LGBTQ+ rights.

Although he helped American Airlines and other companies develop benefits packages that supported LGBTQ+ employees more equitably, Witeck also encouraged leaders to launch employee resource groups. These groups helped to shape and continue to influence company policies as participants identify needs and advocate for resources.

He said this not only helped people with similar values and lived experiences build camaraderie but also connected people from differing backgrounds in a way that taught them to communicate better. This helped normalize LGBTQ+ identity during a time when the queer community was far less visible.

Another early client of his firm was National Coming Out Day, which he explained “wasn’t just a feel-good campaign” in 1993 — the year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was implemented.

“It was intended to mobilize people to be out and visible,” he said.

Witeck and other early LGBTQ+ communications strategists have worked on other ways to make the community more visible too — by communicating data about LGBTQ+ buying power and economic trends to major companies. He specifically underlined that LGBTQ+ people, while cynical and cautious, were loyal to genuine allies — including brands.

Although that was more of an intuitive hunch at the time, today’s research proves that LGBTQ+ people and allies are more loyal to brands that support LGBTQ+ causes, include LGBTQ+ workplace protections, and include depictions of LGBTQ+ stories and people in their advertising.

Early adopters of LGBTQ+ inclusive approaches sometimes faced backlash — but as data emerged about the benefits of openly supporting the queer community, Witeck said companies grew more confident in their ability to survive those transitional times.

“They’d see firsthand the visible contributions and economic opportunities that LGBT people bring, then they’d want to harness that,” he said. “They’d want to hire, retain and address them.”

As more brands became willing to woo LGBTQ+ customers, inclusive ads — like IKEA’s, which was the first to include an openly gay couple in a TV spot — influenced public perception and acceptance. This aided the community’s efforts to shift social and political landscapes over the following decades.

“Companies can play a great storytelling role in normalizing [LGBTQ+ experiences],” said Witeck. “In no small part, they’ve changed the way Americans think.”

A 2020 study conducted by GLAAD and Procter & Gamble showed that cis-het Americans who saw LGBTQ+ representation in advertising and media were significantly more likely to interact with LGBTQ+ people, feel more comfortable around them and support LGBTQ+ rights.

As public acceptance grew, some companies took their commitments to LGBTQ+ people more seriously, prioritizing DEI efforts. Analyzing metrics like the information provided by the CEI is now essential for companies hoping to maintain a positive reputation with LGBTQ+ consumers and prospective employees. As policies or practices fall short, business leaders are challenged to keep up with their competitors who might be outperforming them in this way.

But not every company has been trustworthy. Some have engaged LGBTQ+ people with a more transactional approach in an attempt to earn interest without ever truly becoming allies.

“Companies may create more LGBTQ+ affirming policies because they need to keep up with competition — but I want them to do it authentically,” Witeck underlined.

And the companies that view LGBTQ+ people transactionally aren’t necessarily reaping the benefits of engaging LGBTQ+ people anymore. Spikes in transphobia, for example, have caused some brands to walk back their visible support. But this kind of wishy-washy behavior signals to consumers that some brands don’t know who they are, don’t know who they want to reach, and don’t know what they want to stand for.

Bud Light, for example, was punished by conservatives with a boycott after partnering with Dylan Mulvaney, a trans influencer, in 2023. Before sales even began to tank, two Bud Light marketing executives took a leave of absence and the company announced it would shift its advertising approach to focus on sports and music instead.

“For a company to hire a trans person and then not publicly stand by them is worse, in my opinion, than not hiring a trans person at all,” Mulvaney later told the New York Times.

This kind of pandering resulted in the company losing money from both conservatives and progressives. Major deficits followed.

More people are coming out than ever before, but the American political and social landscape is moving backwards in some ways — as conservatives gain ground with their own messaging about LGBTQ+ people, especially trans youth. This is making it less safe to be visible again.

The HRC reports 84% of people are out to at least one person at work, but many people still choose to be closeted or careful in their workplaces. This includes a quarter of LGBTQ+ young adults who aren’t out at work despite being out in other aspects of their lives. Data collected by LinkedIn shows that only 35% of LGBTQ+ professionals feel they can be authentic at work and 75% have engaged in code-switching at work.

Trans people are more likely to be unemployed and underemployed, and LGBTQ+ people often earn less than their peers. Openly LGBTQ+ business leaders, especially trans people, are still notably absent from the boards of most major companies.

The HRC’s Kelley Robinson called out companies who are scaling down DEI efforts amidst conservative backlash in a recent LinkedIn post where she also celebrated that a record-breaking 1400+ companies are participating in the 2025 Corporate Equality Index.

It shows a palpable divide at a time when LGBTQ+ people are developing stronger expectations about what it means for brands to become allies. In the future, engaging with LGBTQ+ people as customers and employees will only more strongly echo what Witeck has attempted to instill from the start — that leaders who want LGBTQ+ business and talent need to pursue those relationships with integrity.

“Gay people should not be the victims of economics. We should be the drivers,” underlined Witeck. “That’s our whole purpose [as a firm] — to influence positive outcomes, not to settle for second-class status.”