The final host of “Gaydreams” — the first weekly, hour-long radio program on the East Coast to focus on issues and topics relevant to LGBTQ+ listeners — never intended to land that role.

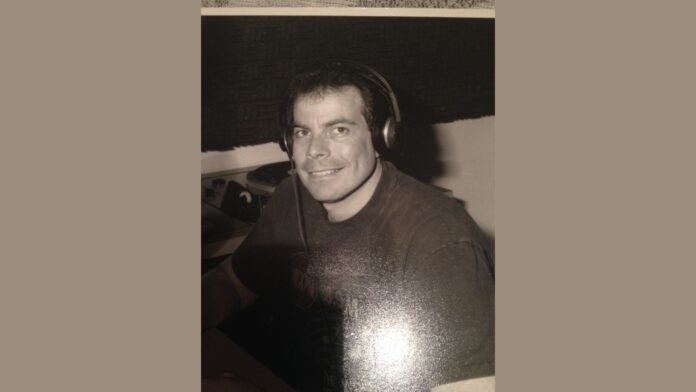

Bert Wylen had been regularly reading the news on air during the program — but neither he nor the station’s management had anticipated that the previous hosts would abruptly move to Los Angeles, leaving Wylen in charge of the Philadelphia-based show.

“I knew very little about public radio, but the engineer at XPN at that time, Tom Terry, told me he would help me in any way he could,” Wylen said. “I started listening to NPR just to get a sample of what good radio would sound like.”

Wylen, who was in his mid-30s at the time, formatted the talk show to be similar to NPR’s “All Things Considered” or “Fresh Air” — offering a “gay version” of those programs throughout the last years that Gaydreams was on the air — from 1990 to 1996.

Although the show had been on the air for almost 20 years when Wylen became host, his new approach led to various awards and wide recognition. (When he left, the air time was taken over by WXPN’s Robert Drake and was rebranded to focus more on music and the arts.)

Some of Wylen’s episodes — 312 recordings — will now be digitized thanks to a $24,450 Recordings at Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources, which was recently awarded to the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives at William Way LGBT Community Center.

“There are huge amounts of media that just can’t be played,” said archivist John Anderies, who explained that the condition of some materials and of the playback equipment is deteriorating — which means it could be accidentally destroyed or damaged should someone try to press play.

These tapes — and other collections like this one — aren’t even listened to by historians until they’re preserved. Anderies has been able to use some clues — like archived issues of PGN and notes that accompany some of the recordings — to determine some of the content.

“You don’t really know what’s on them until you listen to them,” he underlined, noting that he won’t know for sure until the process to digitize them is complete, which he believes will happen in January.

“Once I get the digital files back, that’s when our work starts — listening to everything and cataloging it,” Anderies said.

He expects to hear about some of the most important topics of the 1990s — such as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” marriage equality, and HIV/AIDS as well as interviews with authors, playwrights and musicians of the time.

“We sort of simultaneously find that a lot has changed and a lot has not changed,” he said about what modern people — especially youth — might uncover through listening to the recordings. “Why are we still having these issues in society, or why are we having them again when we thought we may have moved past them?”

“But also, times are different. It is a different time now than it was in the ’90s,” he added. “And I think that that’s instructive for people and interesting to think about — like how either you in your earlier days or people who came before you sort of navigated the world.”

Before taking over Gaydreams, Wylen was part of a different kind of talk show. He and PGN’s Mark Segal hosted a panel of callers via two-way radios on an open signal that covered an approximately 10-block radius in Philadelphia on Saturday afternoons.

The program received attention from angry, homophobic regulars but also served as a respite for people who otherwise didn’t have space to be themselves or listen to people with shared experiences. It prepared him for his later work with “Gaydreams.”

“My primary focus was helping the gay person who was suffering either in the closet or out of the closet with very low self esteem,” Wylen said. “So it was therapeutic for them.”

“It was therapeutic for me,” he added, noting that the show gave him a sense of purpose during a time in his life when he felt like a “total wreck of a human being.”

He was newly sober and had become homeless and was couch-surfing while hosting the show, working odd jobs to earn any money — as the station didn’t pay him or cover costs associated with producing content for the first four years he was on the air.

Wylen said it took launching a public campaign against the radio station for WXPN to start giving him a paycheck. One month, he survived solely on leftover pretzels given to him by a kind vendor in Rittenhouse Square. Still, the work was part of what Wylen, an atheist, called his ministry — a “ministry to help gay people — especially gay kids.”

One of his fondest memories occurred while he was Christmas shopping in a department store with a friend. A woman — who had been looking around to see if anyone was watching — approached Wylen to whisper “Thank you” before running away. Similar moments and countless letters from supporters throughout his tenure as host made him realize his impact.

“Most of the letters I got were from gay kids who listened to gay dreams with headphones on so that nobody would know what they were listening to,” he said.

“I had many, many occasions where I had the satisfaction of knowing that I had touched people’s hearts and helped change their lives,” he added. “What I know now, I could have done a much better job of that.”