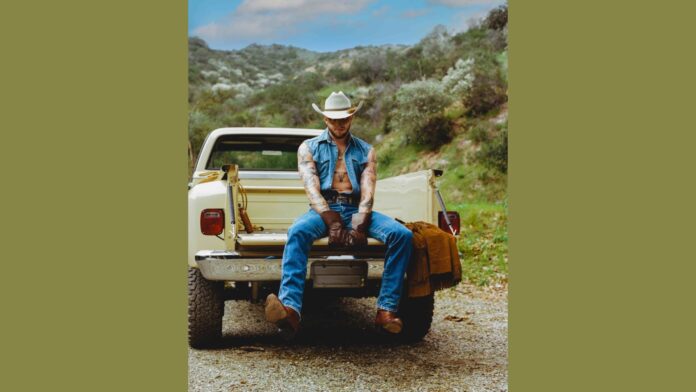

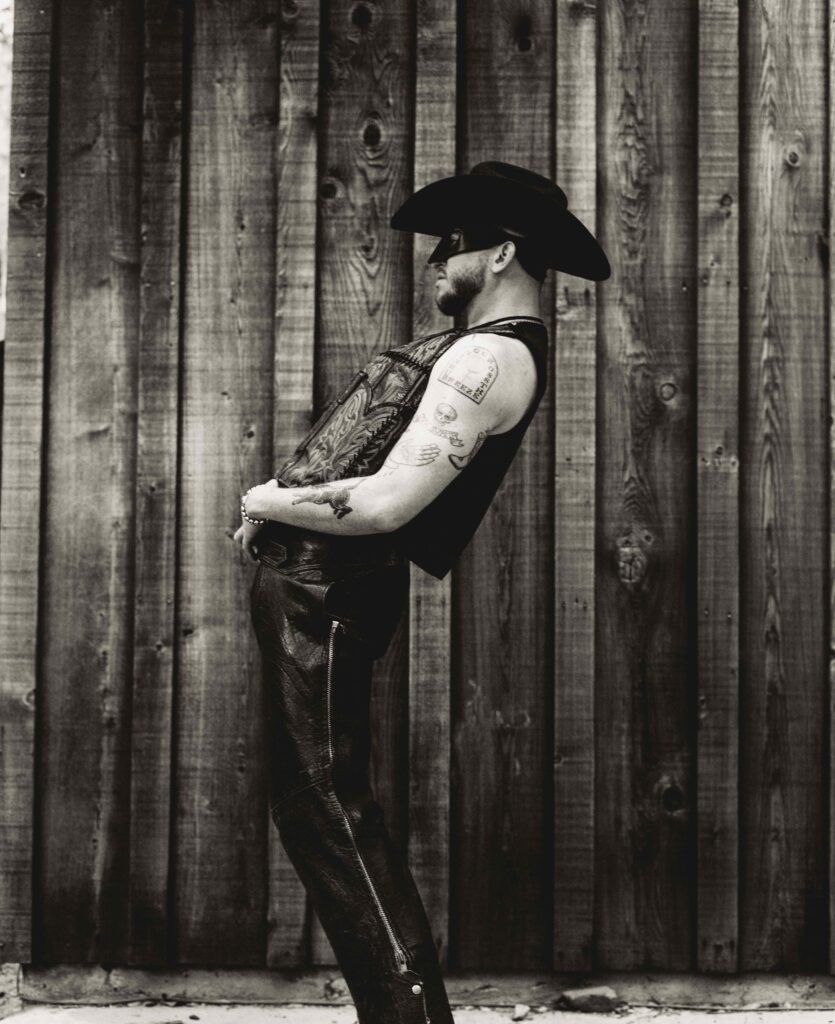

Orville Peck’s sexy video for “Cowboys Are Frequently Secretly Fond of Each Other” is unabashedly queer in ways the country music genre hasn’t historically seen. In it, Peck sings his cover of Latin country musician Ned Sublette’s 1981 song as a collaboration with Willie Nelson — who, inspired by “Brokeback Mountain,” performed a solo version of the song in 2006 — but now, especially, Peck’s modern take feels like a very welcome subversion of what we’ve come to know as country music. Man hands graze man butts. Women slow dance intimately with other women. Twinks in tight blue jeans bale hay. In other words, this saloon is serving more than beer.

Ever the ally, it was actually Nelson’s idea to revisit the song with Peck, who recently released the tune as part of “Stampede Vol. 1,” his first duets album. The seven-song collection also features a collaboration with Elton John on “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” and “Chemical Sunset” with fellow queer Americana singer-songwriter Allison Russell. “I wouldn’t say it’s as traditionally in line with the rest of my albums,” he tells me. “I would say it’s more conceptual just based on the collaborative nature of it.”

Openly and unapologetically gay, Peck released his first album in 2019, the self-produced “Pony.” Since then, he has steadily risen to prominence as one of the few modern trailblazing artists redefining country music — challenging the old notion that only straight, white people can strum a guitar and sing with a backwoods twang.

Before setting off on his “Stampede” headlining summer tour, I spoke with Peck about why he’s letting more of his face peak out of his signature face mask, what other allies can learn from Willie Nelson and the “beautiful gift” of inspiring kids in rural communities to be themselves.

As a longtime country fan, I feel like I’ve been manifesting you in various ways since I was a kid who grew up on this music. During interviews with country superstars like Dolly and Reba who I’ve interviewed over the years, I’ve even asked them, as if they had the answer: “Why can’t we have an out gay male country artist?” And here you are. What does it feel like to know that you are what so many LGBTQ+ country fans have been manifesting and hoping for for decades?

Wow, that’s so lovely. Thank you. That means a lot to me. It doesn’t escape me because I was also one of those fans. I, like a ton of queer people, grew up loving country music and relating to all sorts of country, both male and female, usually especially females, to be honest. So it feels amazing because I am also one of those fans that grew up loving country and longed to see someone like me or someone sort of like me, even close to like me, making the music that I love.

So getting to do this song with Willie: I can’t understate how important and full circle it is for just me as a person to know that Willie Nelson is on this track doing this song with me. It’s really affirming and really validating for me and I imagine a lot of people, which is cool. But it’s funny because I always say country music appeals to gay and queer people because it’s about storytelling, yearning, loss and unrequited love. All the classic country songs I can think of, I always say they feel like the queer experience to me. It doesn’t surprise me whatsoever that queer people are drawn to country music.

And then, of course, you mix in the campy flamboyance of someone like Dolly.

Exactly. Put rhinestones on it and it’s like, fuck, it’s over.

And speaking of your collaboration with Willie — it’s also such a powerful nod to straight male allyship.

Totally. This term “ally” gets used a lot these days. In the climate of the world right now, where queer people, trans people and drag queens are so villainized and under actual serious threats of violence to their lives, it’s not good enough just to be accepting or friends with a gay person. I don’t think that’s enough. Real allyship in times like these [is] standing next to us with absolutely no ambiguity and essentially saying, “We are here right next to you and we support you.” And that’s exactly what Willie did by doing this video and song.

What is the impact that you hope this collaboration has?

I’ve always grown up with a lot of straight guys as my friends, because I used to skateboard and play in punk bands and all that stuff. All I had around me were straight boys. They were always just my buddies. And so I’ve seen that kind of allyship in my personal life since I was quite young, which is fantastic. But I’ve also seen this sort of performative allyship where it’s like, “Well, yes, of course, being accepting of queer people, that’s the bare minimum. That should just be. People should be accepting of everyone.” That isn’t allyship. Allyship is being vocally in support and standing next to us, especially in a time like now, when we need it so much.

Given that we’ve only recently seen more openly LGBTQ+ artists in country music, who gave you the courage to step up and decide to make a place for yourself within the genre?

I really attribute that to my parents and my family. I never really had to come out because I think my parents always sort of knew. I have two older brothers who are both straight, and I think my parents always knew that I had a little sugar in my tank. They always made a really adamant effort to let me know that I was no different than anybody and that I could do whatever I wanted to do and I can be whoever I wanted to be. Because I think that they knew and could see that that was something that was not encouraged in a lot of queer kids. I was really incredibly fortunate to just have parents that wanted to encourage that side of me. I also grew up with this ambition to just not let anybody tell me I can’t do something for any reason. And so when someone excludes me, it makes me want to include myself even more and kick the door down and then sit at the table and put my feet up on the table. That was instilled in me so strongly as a kid by my parents. We grew up in South Africa during apartheid. I’m from a mixed-race family. I saw firsthand the treatment of people for being different. And I think my parents just really wanted to instill in us that nothing makes anybody less than someone else.

It seems every decade or so, we go through a redefining of country music. Where do you think we’re at now with the genre?

I think we are at a place in the genre that’s so exciting because there’s sort of a reclaiming happening. Because the truth is anybody should feel welcome to be a part of country as a culture and as a genre because the fact is it’s literally just built off of so many different inspirations and cultures to begin with. Country music, just in the instrumentation alone, is African, Hawaiian and European. It was built when America was in its early days of being this huge melting pot.

So I think what we’re learning and realizing as a society now is, “Oh, wait, I don’t have to be a white straight person that lives in the South in order to be a part of this culture. This can also be my culture, and I can make it my culture, and I can be a part of it.” I think it’s really cool that so many artists are claiming their place in it because it is truly the most diverse American genre, and it is for everybody. It should represent how diverse its roots are. It should be representative in how the genre looks today. And I think it’s finally catching up.

You’ve said the masks you wear as shields allow you to feel more comfortable to be vulnerable as an artist. Since we’re seeing more of your face now, does that mean you’re feeling a little safer to be more musically vulnerable these days?

I do. I made the mask at a time for several reasons. I think it was partly something kind of artistic and bold that I wanted to do and wanted to see within country that I hadn’t seen before. I wanted there to be like a David Bowie of country kind of vibe and make something artistic. And then I think it also inadvertently protected me and my anonymity and started to ease my transition into success because I’m not someone naturally built for that transition. I think I would’ve gone crazy if I didn’t have that buffer. It was really helpful for me on a personal level. Also, yeah, I started to realize that it allowed me to be more vulnerable as an artist and share my stories. It just gave me a little bit of confidence.

But it’s funny, with each album I’ve been building so much more confidence of my own, and the mask has felt less and less important to me, even though I will always be grateful to it and love it and love all the iterations of it. But I think in my personal and artistic journey to authenticity and the most vulnerability and the most openness, the mask has to represent that. As I evolve, I think that has to evolve as well.

When you first decided that you were going to wear the mask, did you foresee a day in which the mask might become a topic of conversation on social media among very thirsty queer and gay men?

[Laughs.] No. All I ever wanted to do was just make one album, which I did practically completely alone and with $300 in my pocket. So every single thing that’s ever happened since I put out “Pony” has been sort of a surprise and a lovely cherry on top for me. So no, I’ve never envisioned most of the things that have happened in my career.

For the tour, have you already started the process of deciding which masks you’ll pack? Is that a torturous process?

Yep. It’s always a very specific discussion with my stylist. There’s a new design, obviously, so it’s an exciting time because we get to see what we come up with color-wise and to match all my different outfits. Just on styling in general, unfortunately, I’ve kind of screwed myself because we killed all my styling so early on because my stylist is so amazing, and so every single time I have to do something, we’re like, “Fuck, how are we going to top what we’ve already done?” So there’s a whole archival museum of all the outfits I’ve ever worn and we have to look at those and make sure we’re not repeating anything. It’s a whole process.

How did you arrive at the name “Stampede” for the tour and the album?

Well, I always want to keep it horse-y with my album titles. There’s a little bit of a theme in my album titles, obviously. Even since the last album, I was thinking, “Well, what could I call it that’s still in keeping with my tradition with what I name my albums?” And then as I started to look at just all the different artists that are on this album, I was like, “I know exactly what this is. It’s a stampede.”

My vote for “Stampede Vol. 2” is for a Dolly duet, and also one with k.d. lang.

Oh, I love k.d. Some of the original queer country that a lot of people don’t even really realize. She was a real trailblazer. “Trail of Broken Hearts” is an amazing song.

Seeing you as part of the country music genre sends a positive message to queer kids who are living through a precarious time for LGBTQ+ people. What do you hope the message is for a young boy in rural America who dreams of being like you one day?

That you already are loved and there are people out there that are not members of our community that will love you for exactly who you are. The coolest thing about it being Willie Nelson, not only is he one of my idols, but there isn’t a single country music fan that doesn’t like Willie Nelson. He’s such an icon and such a legend, and so for him, more than all of these other people, to stand up and do this, I think it can give people a lot of comfort and reassurance that there are people out there that stand with us and are with us.

Something I never anticipated is, I guess, being an inspiration to, well, anyone, really. And so now that that has become the case, I take it really seriously, actually. It’s been a really beautiful gift to me to be able to hear the stories from people of just their experiences and how my music maybe has affected them or encouraged them. It’s kind of become the most beautiful and important part of my career — just feeling the impact that it has on people. So if that gets to be broadened and helps someone maybe in a situation where they feel they’re excluded, that’s everything to me. I think that’s really important.

Chris Azzopardi is the Editorial Director of Pride Source Media Group and Q Syndicate, the national LGBTQ+ wire service. He has interviewed a multitude of superstars, including Cher, Meryl Streep, Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.