According to the Movement Advancement Project, almost 40% of LGBTQ+ adults are disabled, and the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System puts that figure above 50% for trans adults. Research clearly points in a distinct direction: LGBTQ+ people are more likely than the general population to experience disability.

Unfortunately, they’re not any more protected from ableism — and access to the LGBTQ+ community is littered with roadblocks for disabled people. That is especially true for those exploring nightlife, including entertainers who want this to change.

“Philly is an old city, and it’s got lots of old infrastructure,” said burlesque artist Essa Terick, who goes by Tahnee Simone when they’re not on stage.

Most venues in Philly weren’t designed with performing in mind. Steep, narrow stairwells lead to second or third stories where flexible-use parlor rooms are converted for small crowds. First-floor options require performers to navigate around seating for diners. There aren’t designated stages, dressing rooms or other typical amenities.

These are massive physical hurdles for disabled performers — who cram into public bathrooms among able-bodied castmates to get ready, lug their suitcases and other costumes or gear up flights of steps, and constantly adapt to environments that don’t accommodate their needs.

While information about steps and ADA-compliant bathrooms tend to be more available, artists noted that producers tend to be less informed about the broader ways they can advocate for and work with disabled people to find solutions to constraints. For instance, many believe they should be more upfront about the atmosphere and sensory experience of a specific venue — as lighting, volume and other aspects aren’t consistent. This is helpful information for neurodivergent people, those with neurological or mobility concerns, people with vision or hearing differences, and more.

“It shouldn’t be on disabled performers to self-disclose their disabilities and what their needs are because not all of us will know what our needs are in that specific space,” Essa Terick said, explaining that producers — who know the layout and challenges of their venues — should be able to explain what the space is like, discuss limitations, and consider how to accommodate each performer before a show launches.

Many disabled performers, Essa Terick noted, have difficulty describing their disability to able-bodied people — especially when they lack a diagnosis and language for their experiences or live with various symptoms and conditions.

This makes it harder to self-advocate.

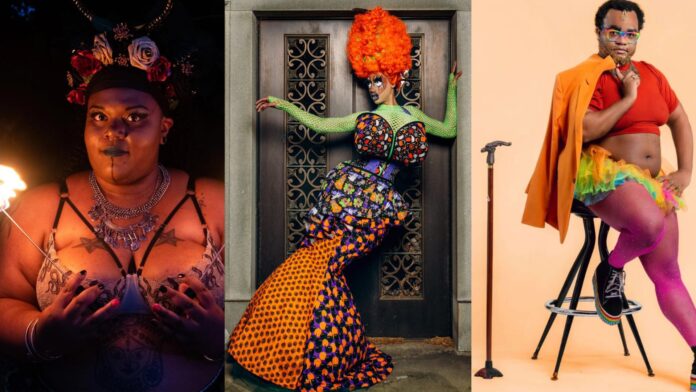

Avery Goodname, a Philly drag clown, doesn’t always feel comfortable speaking up for herself and others. She’s been present when performers joke about disabled people behind their backs, harshly critique their work, and bully or reject them — which taught her that people aren’t as disability-positive as they want to appear.

She sometimes needs the support of her partner to get ready, which often goes misunderstood.

“They think they see a drag artist who is unprepared and unprofessional rather than someone who is disabled asking for accommodation from their fellow castmates,” she said.

Goodname struggles with stamina and endurance due to her disability and needs to manage more serious symptoms which flare up at night. This creates what she feels is distance between her and the nightlife community because she often can’t hang out after shows and requires more downtime to recover.

Fans and community members aren’t always respectful of her need for space, which makes her feel pressured to be a “perfectly curated person” whenever she’s in public — which she said she doesn’t always have the spoons to do.

Producers aren’t understanding either. The performer was coerced into dropping out of a musical after her symptoms caused her to miss two rehearsals. She said it felt like producers were punishing her for having a disability, as they didn’t try to collaborate or problem-solve to find ways to continue.

Some gigs — especially higher paying opportunities — can be physically and emotionally demanding, she said, but she and other disabled performers know their limitations.

“I can handle myself. I’ve been able to handle myself,” she underlined. “I wouldn’t be here if I wasn’t able to handle myself.”

Goodname — who appeared on season 5 of reality series “Camp Wannakiki” — felt forced to leave that show too, after she was met with resistance when requesting accommodations. She recently spoke with producers about returning for a future season. She said producers are willing to listen to feedback regarding accommodations this time, but she’s still uncertain about the show’s desire to implement any solutions.

“I wish that disabled people have a little more agency in deciding what is within their capabilities,” she emphasized.

She noted that people don’t often know how to be allies to disabled people and their attempts to show care are often full of unconscious biases, which show whenever they’re inconvenienced or challenged to be more proactive. She said allies should do more listening, less leading, and learn to cope with their own discomfort.

“People are only OK with someone being disabled as not as long as the symptoms of the disability are not happening in front of them,” she said, underlining that people are especially impatient and unsupportive to neurodivergent people and those with neurological or mental health concerns — requiring them to mask their symptoms and identities to fit in.

“Find the people who are not only willing to be accommodating but who are willing to learn and understand and take care of you as a disabled person in nightlife,” she said. “Because we deserve equal access to nightlife as every single able-bodied person. We just need to come at it a bit differently, and the adjustments are really not that hard for other people to make.”

Deej McCoy, who performs under the name Deej Nutz, is autistic and has ADHD. They underlined that people should not be made to keep any aspects of themselves — including neurodivergence, disability and mental-health conditions — in a metaphorical closet.

“I also have multiple sclerosis — and before I was diagnosed, I started getting some visual disturbances in my left eye,” they explained. “And so I ended up needing to start wearing an eyepatch because I was getting double vision.”

Rather than try to hide signs of their disability, McCoy built it into their act, developing a drag character around the eyepatch. Although some performers are anxious to try using mobility aids on stage, McCoy enjoys using their cane because it supports their balance. They’re also working on incorporating a mobile stool into their act because the wheels allow them to move more swiftly in tight spaces.

They noted that disabled artists are sometimes disregarded as though they’re less entertaining or less talented but highlighted that creative accommodations can enhance a performance and make the experience more fun for an audience.

Essa Terick relied on painkillers and alcohol to make it through shows in the past before realizing they also needed to adapt their performance style for the sake of their health. They now take an improvisational approach — guided by a narrative storyline rather than strict choreography — and make each show a little different than the others. Their movements might change based on how their body is feeling each night and include seated options, laying on the floor, and crawling when needed.

“It’s a constant relationship to the musicality, to the audience, and to my body,” they explained. “I try to have it be a free-flowing dialogue because I’m not just showing my body. I’m in relationship to it.”

The commercialization of drag has promoted a mostly able-bodied image of what the art is — leaning on flashy tricks and athletic movements to wow audiences. But those versions of that art offer a limited view.

Producers have engaged in ableist microaggressions — reminding artists that they seek “elevated” performances. Essa Terick said this and other language can feel passive-aggressive and vague while excluding and minimizing the impact of art that is less polished, costumed or athletic.

“As I perform with folks who have more radical views of who the community is and who the art is for, I have found way more freedom and wiggle room and ability to show up as I am,” they said, noting that producers who double as performers and those who are also disabled or marginalized in other ways are quicker to recognize their value.

“One of the scariest things that you experience as a human being is to realize that you have been — that you are — living with an incredibly flawed mindset,” said Avery Goodname about ableist mentalities. “But that doesn’t mean [change] doesn’t need to happen.”