The United Methodist Church recently voted to eliminate problematic language and stances regarding LGBTQ+ people that exist in the Book of Discipline — which outlines the denomination’s beliefs, laws, standards and doctrines. During a quadrennial conference (known as General Conference) which meets to discuss the denomination’s policies and procedures, those present also voted to end the longstanding ban on openly LGBTQ+ pastors.

A provision which streamlines the path to reinstate defrocked pastors was also approved. This offers people like Stroud – who was defrocked due to her queer identity in 2004 following a very public church trial — an expedited route back to ministry.

“I’ve been the reverend and I’ve been the doctor — but I’ve never been the reverend doctor,” Stroud laughed as she told PGN about her own decision to pursue reinstatement.

Stroud initially came out as a lesbian in college. She said she already knew who she was and understood the denomination’s discriminatory policies when she decided to go to seminary in the early ’90s.

She attended Union Theological Seminary in New York City. While she studied, she worked as a freelance journalist — helping to start an LGBTQ+ newspaper — and got involved in ACT UP.

“I came to seminary wanting to deal with big questions and learn about changing the world and about life and death and the meaning of things — and I actually learned as much about that from ACT UP that I did from seminary,” she said.

Stroud came home to eastern Pennsylvania where she pursued ordination with the support of a church she attended as a young adult with the encouragement of her role models.

“I grew up United Methodist. My parents grew up Methodist,” said Stroud. “So I’m sort of this rare bird in the sense that I have this longstanding — not just lifelong but generational — identity as a United Methodist.”

At the time of her ordination, she was shielded by a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” approach to the process, but when she found a partner, Stroud grew frustrated by the secrecy. Her experience with ACT UP taught her that successful direct actions are often planned in a way that’s open and transparent. This was a guiding principle in the intentional steps she took to come out publicly — including meeting with her bishop and members of her congregation as she developed her plans.

“The church was packed,” Stroud said with a joyous energy in her voice about the morning she came out during a sermon. “There was just this wonderful energy.”

But then she was brought up on charges. The disciplinary process was designed to help someone who had done something wrong reconcile with repentance — which Stroud knew wasn’t relevant to her situation. She was offered opportunities to surrender her credentials but decided if the church wanted to stand behind discriminatory values, she wasn’t going to let them do it behind closed doors.

“Being the face of this whole thing — being the object of so much attention was really uncomfortable and exhausting,” she said. “For me, I never wanted to be identified with just one thing.”

“I don’t think I ever dealt with the cost to me until much later — and maybe I still haven’t fully dealt with it,” she added.

It’s been 20 years since the trial — and Stroud’s life has changed dramatically. She’s raised a child from infancy to early stages of adulthood. She’s been through a divorce, cancer and various other challenges.

When she and her family moved to New Jersey, they started attending another LGBTQ+ affirming United Methodist church in Trenton. She said the pair was open to finding a new denomination but the small church they found just felt right for their child and their family at the time and have continued to feel that way.

She said she doesn’t know how much the other attendees know about her past and is glad it’s a space where she isn’t known primarily for the defrocking.

Stroud earned a second master’s degree at Lutheran Seminary and a PhD at Princeton — where she said colleagues who have known her for years might not be aware of her history or, if they do, don’t think of it often.

“Personally, it’s been important for me to have places where I’m under the radar just because my soul just needs that rest,” she said.

Stroud might have found some rest — but her quiet life hasn’t been easy. Mentors of hers at the time of the trial had warned her that she might lose a lot of security and financial stability should she come out. Although that didn’t deter her, she has struggled at times since.

“I don’t have the college fund for my daughter or the retirement savings that I think I ought to have at this stage of life,” said Stroud, who is now in her 50s. “So yeah, there have been a lot of practical costs along the way.”

“I’ve had periods of unemployment and periods of financial desperation on the academic job market,” she said. “I got my [PhD] in 2018, so for the past six years, I’ve been in contingent positions — sometimes not knowing one semester to the next if I would be working, if I would have income.”

“There have been times when I thought, ‘Damn, my first career didn’t work out and my second one isn’t working out either,’” she said.

When friends who’d supported her during the trial asked if she’d consider coming back to the church should the policy change, she said she wasn’t initially convinced. When the updates were passed, she was initially angry — disappointed that the denomination clung to the problematic language and policies for so long.

“I don’t think I really knew what I was going to do until I did it,” she said about requesting for her credentials to be restored. “It felt like something I had to do to finish what I started.”

“I felt so strongly that I was called to be a minister,” Stroud said. “That’s why I went through this [trial] in the first place — because it was that important.”

“I think I had been letting it feel less important to me as a way of coping,” she underlined, adding that getting reinstated was also for the congregants and allies or other LGBTQ+ people who have been waiting for this day to come.

Stroud was officially welcomed back on May 21, during a local conference for eastern Pennsylvania pastors and church leaders held at the Wildwoods Convention Center. About 200 ordained clergy voted by an overwhelming majority to readmit Stroud as an ordained elder.

Old friends and new supporters greeted Stroud with emotional cheering and singing after she was presented with a red stole, symbolizing her connection to the church as a clergy member. She then walked with the group of pastors in a formal procession into the larger conference.

“It didn’t feel like it was just me or just for me,” she said.

Bishop John Schol — who worked with Stroud at her first church appointment in West Chester, Pennsylvania — ordained new ministers during a service. After the ordinands were presented to the congregation, those gathered sang hymns written by openly gay United Methodist worship leader and songwriter Mark Miller.

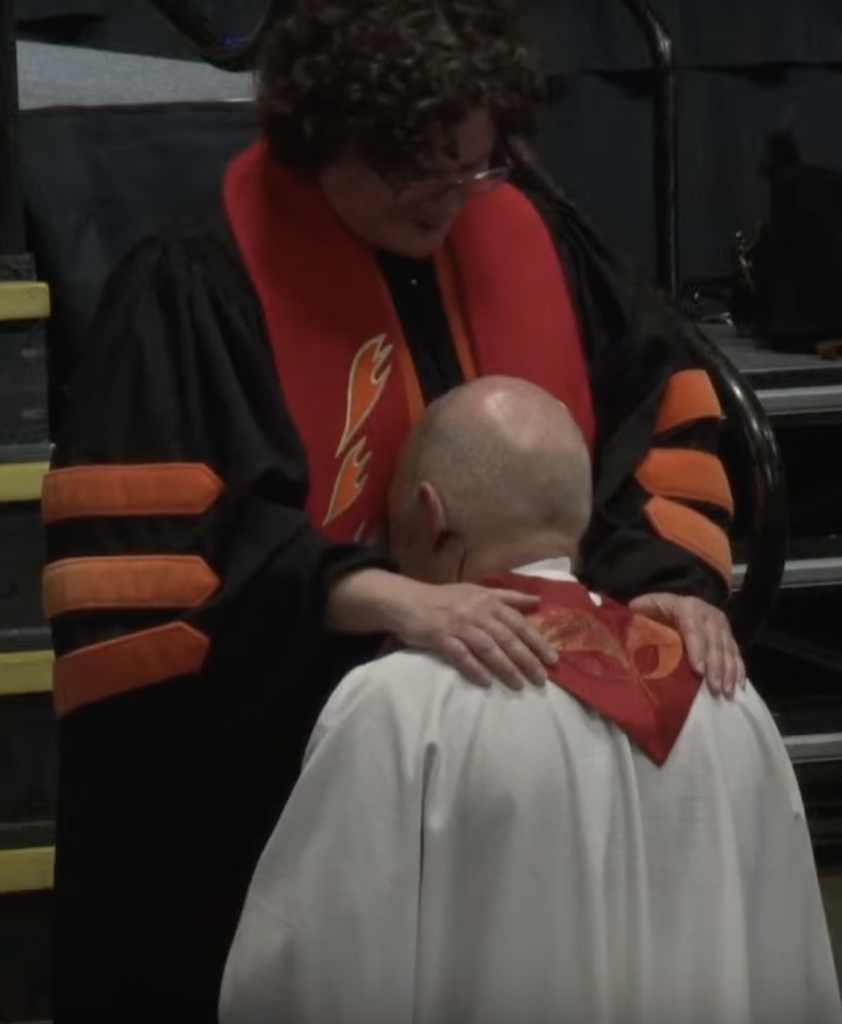

During the song “Child of God” — which has a verse that reads, “No matter what the Church says / Decisions, pronouncements on you / You are a child, you are a child of God” — Schol left the stage to kneel in front of Stroud, who placed her hands on him in prayer.

“Draw the circle wide. Draw it wider still. Let this be our song. No one stands alone,” the group sang next as they formed a circle around the two.