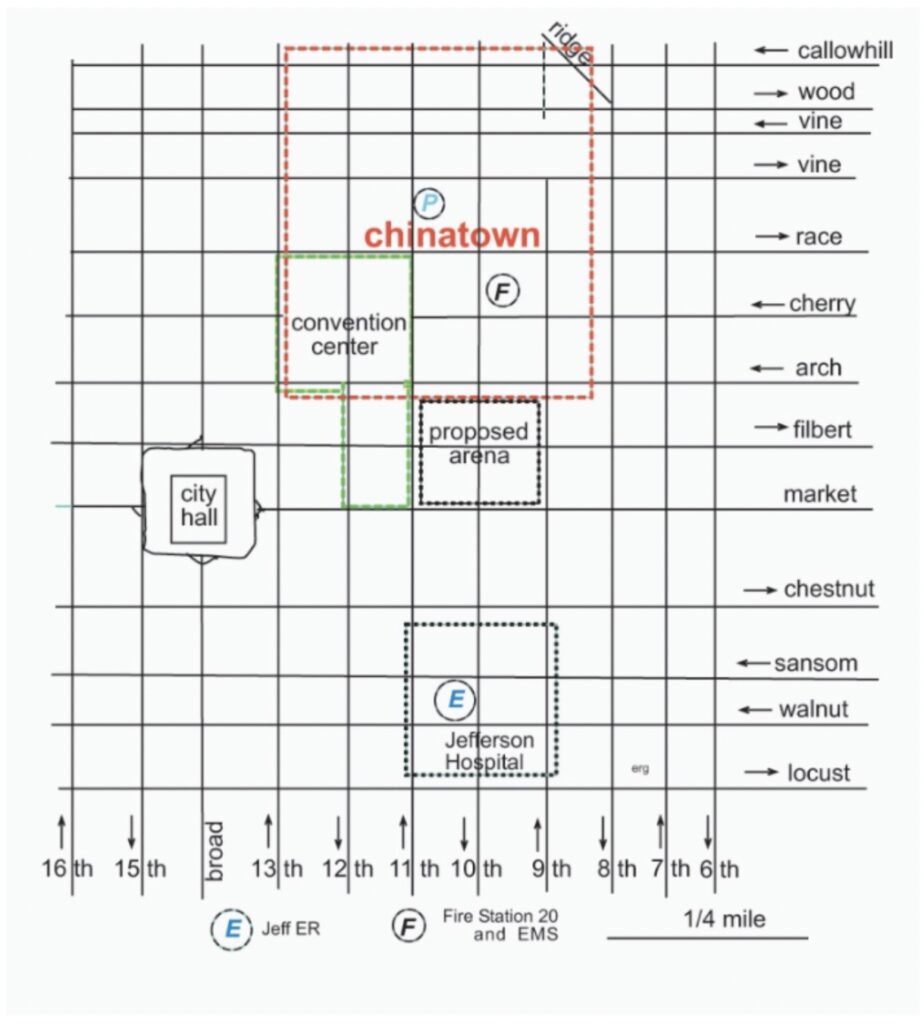

76 Place, an arena proposed by the Philadelphia 76ers, could become a new home for the basketball team. It would sit at the border of Chinatown and the Gayborhood — redeveloping a third of the Fashion District mall and spilling over across Filbert Street.

The team has claimed that approximately 30,000 people have signed petitions in support of the project, but community members are speaking out against it. LGBTQ+ people who live in or utilize the Gayborhood are organizing as “No Arena Gayborhood.”

Despite developers speaking about the project as though it’s a “done deal,” Apurva Tandon, one of the group’s organizers, said the proposed project has not been approved and faces both logistical and legislative challenges.

“That’s why people are putting so much energy and time into actually mobilizing the community,” she said, underlining that activism efforts have so far been successful in slowing down the process to develop the site. Here are some of the group’s major concerns:

Community space

“It’s only been less than a decade since we renovated those properties, and now we’re already talking about tearing down half of it,” said Rizzo Enro, who noted that the proposed site was recently renovated using millions of dollars of public funds. “I just feel that’s a misallocation of public funds.”

He emphasized that vacant commercial space could be converted for public use — proposing recreation leaders, educational institutions, and small business startups as potential partners. Other members of the group dreamed of public art, an entertainment venue, rotating museum exhibits, green space, housing and more. The Save Chinatown Coalition, which is also against the arena, has similarly taken time to imagine other possibilities for the space. Some members of the No Arena Gayborhood group envision a project that would connect both neighborhoods.

“The arena is set to be at the intersection of two historic neighborhoods — the Gayborhood and Chinatown,” added Tandon. “Imagine a world where we can offer programming and space that is inspired by the history of the area?”

Many are additionally concerned about longevity, noting that arenas have a typical lifespan of approximately 30 years. No Arena Gayborhood is asking what happens when the arena is no longer considered modern, no longer profitable, or no longer meets the needs of the teams who utilize it. This is currently a problem for neighborhoods adjacent to a newly built arena that will likely be abandoned in Washington, DC.

LGBTQ+ erasure

“These sorts of developments really don’t cater to the neighbors that live around them,” said Tandon, underlining that the landscape of the neighborhoods surrounding arenas tend to shift to cater to incoming fans instead of residents.

Impact studies demonstrate that new arenas negatively impact local residents and decimate small businesses, which struggle to withstand the impact of construction and struggle to survive gentrification. An impact study on 76 Place confirmed that this is a possibility here too.

Members spoke about fears that the Gayborhood would become a piece of history rather than remain a part of the active community.

“Our queer elders created and maintained this space through some of the hardest times in history,” said Theresa Garcia. “It’s filled with some of the most historic queer landmarks and local businesses in the country. That means the world to someone like me, but absolutely nothing to a developer who can’t profit off those things.”

“A thriving queer community isn’t something every city gets to have; I fear we won’t realize how special the Gayborhood is until it’s gone,” she underlined.

“The Gayborhood is a very fragile microcosm,” added Patrick Coué.

“Queer neighborhoods across America are in a state of transition. As we see growing social acceptance of queer communities and the increase of virtual spaces, we also see a decline in physical spaces in urban centers — but we still need these spaces,” said Oliver Truong. “Members of our community are still fighting for inclusion and visibility. Fewer businesses mean fewer festivals, fewer events, less visibility. The loss of physical queers spaces puts the Philly queer community at great risk.”

Traffic and accessibility

The city is considering traffic needs, and the proposal has changed to meet some of the city’s and community’s concerns. However, there would still be major changes and disruptions.

“Who proposes an arena of 18,500 people and includes no parking?” said Robert Tunick, who noted that the 76ers expect approximately 6,000 additional cars on game days. Because parking lots are not part of the proposed plans, drivers will need to look for it on the streets or in local lots and garages. He underlined that people will flood out of the arena into the city’s narrow, historic streets — which are not designed for efficient traffic flow — and will be impacted by increased foot traffic.

“Even if you don’t live in the neighborhood, it will become difficult for people to actually access resources because of how blockaded the streets could become,” Tandon said, emphasizing that people who live even beyond the city limits come to the Gayborhood for queer-oriented services, support groups, recovery meetings, healthcare needs and more.

“The design of the project is meant to cater to a totally different crowd — to people who don’t live in the neighborhood and do not utilize the neighborhood, and it all comes at the expense of people who do,” she said, noting that even less obvious quality-of-life issues will arise — such as health concerns related to increased air pollution.

A recent lawsuit requires Philadelphia to improve curb ramps to promote sidewalk accessibility, but No Arena Gayborhood activists underlined that sidewalks will become inaccessible in other ways due to this proposed construction. Pedestrians could be forced to walk into the road or to cross the street due to limited sidewalk width, a current problem with work happening outdoors at Reading Terminal Market. This negatively affects disabled pedestrians and creates safety concerns.

Additionally, multiple roads would be closed or slowed on game days, and the plan would completely eliminate a portion of Filbert Street — creating a physical barrier between the Gayborhood and major destinations, such as Reading Terminal Market. This could be a problem for emergency vehicles that are housed at a nearby fire station and those seeking care at nearby Penn health centers and Jefferson Hospital, as all foot and vehicle traffic would be redirected around the new building.

LGBTQ+ safety

The current proposal notes that people would likely plan to park within a half-mile radius of the arena, which would include Gayborhood streets.

“Philly sports fans are known to be rowdy,” Tunick said, underlining that they might not keep their own anti-LGBTQ+ opinions to themselves when passing through the space. “Would people in the Gayborhood feel safe?”

“Will [spectators] be respectful to people who are transgender, nonbinary — to people who are going in and out of bars wearing leather or wearing drag?” he asked, adding that LGBTQ+ people might not feel comfortable being themselves in the Gayborhood anymore.

Others agreed that growing misconceptions around trans identity, drag performances, and other LGBTQ+ activities and expressions have made them feel less protected — and this project feels that it could put them at greater risk. Some who don’t currently live in the Gayborhood said they might not use the spaces as frequently out of fear that the two groups might clash.

“The Gayborhood is supposed to be a safe space, and even if it doesn’t create an actual problem, it’s going to create a perceived problem — where people are going to feel like, ‘I can’t go out. I have to stay home when they have a game,’” underlined Tunick.

How to get involved

The coalition of advocacy groups that oppose the arena has put together a dossier of the research on the subject.

Tandon noted that Mark Squilla, the city councilmember representing the Gayborhood, recently introduced legislation naming a street after Michael Hinson, a gay activist and leader. She invited him to take allyship a step further by “protecting the streets that queer people rely on.” Tandon hopes Squilla will join No Arena Gayborhood at an information-packed happy hour the group is hosting.

“This is just meant to gather the community and to send the message that the Gayborhood and the queer community has a stake in this,” she underlined. “And we will be heard.”

The No Arena Gayborhood happy hour and information session will take place 5:30-7:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 28 at Cockatoo, 208 S. 13th St.