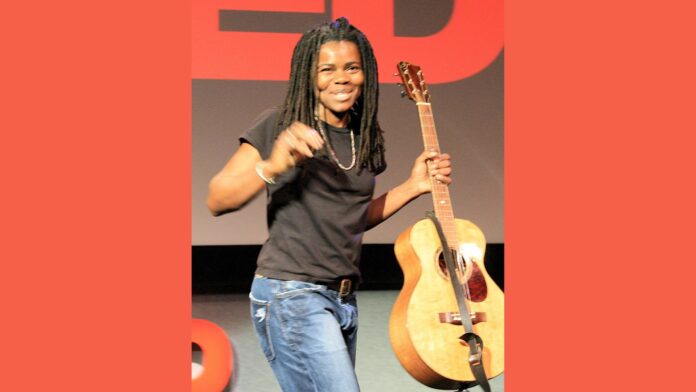

Ten days ago, I was sobbing my way through one of the best Grammys in recent memory and thinking about how much music has impacted me as a storyteller. The performances by two iconic figures from my youth — Tracy Chapman and Joni Mitchell — didn’t just make me cry from their sheer beauty and power, they made me journey back to the times when those two women’s voices and the poetry of their lyrics spoke to me, and even for me, as I navigated some of the most difficult periods of my life.

As I wrote during the Grammys on Twitter/X, “As a young queer woman I will never forget hearing Tracy Chapman singing Fast Car the first time. It imprinted me forever. Cried real tears watching her perform at the #GRAMMYs.”

Music is so omnipresent in our society that it often seems more like a constant background buzz rather than the powerful directional force it often is. In this 50th year of hip-hop, I think about how the voices of the early women of hip-hop — Queen Latifah, Da Brat, Missy Elliott, Lauryn Hill and Philly’s own Eve — influenced my politics and informed my thinking as a subversive queer writer. Knowing that both Queen Latifah and Da Brat are lesbians added even more power to their work for me.

Few singer/songwriters are as deeply embedded in my consciousness as Joni Mitchell, who was a constant refrain throughout my troubled and complex teen years during which I was expelled from Girls’ High for being a lesbian and spent some weeks in an adolescent psychiatric ward for conversion therapy.

Joni Mitchell was also a touchstone for my late wife and me. Music was preeminent for my wife, Maddy Gold, who was a well-known local artist and a design professor at Drexel University. Although we had very different musical tastes — she was a total jazz head and my tastes were more eclectic — we would spend hours sharing music that we each loved. Joni Mitchell’s jazz albums were beloved by us both and also a touchstone to when we were first lovers in high school.

When Tracy Chapman performed at the Grammys, it sent me spiraling back to the late ’80s, which was a tumultuous time for me. I was one of the top journalists in the country covering AIDS and I was also traveling to the UK every few weeks to be with my then-partner, a filmmaker in London. When I think of Chapman’s iconic ballad, “Fast Car,” which is about deferred dreams, lost promise, inescapable poverty and personal displacement, I recall walking through a foreign airport and hearing it — this very American song that I loved — and how much it moved me in that moment.

Songs are so often love letters. My wife would regularly text me videos of songs that made her think of me and us, and her love for me. There are so many songs over my life that call up times and places and resonate for what they say about society or our interior spaces or — like “Fast Car,” love and loss, dreams deferred and promises sundered.

On the same album as “Fast Car” is another song by Chapman that imprinted me: “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution.” In it she writes, “Don’t you know/Talkin’ ‘bout a revolution?/It sounds like a whisper/’Cause finally the tables are starting to turn/Talkin’ ’bout a revolution.”

The stories of our lives, the love letters we write to our past, present and future selves, are embedded in songs like “Fast Car.” There weren’t many out performers in 1988 when Chapman’s song landed on the Billboard 100. At this year’s female-centric Grammys, with more women performing and winning than in any other year, the big winners of the night were all women — Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus, Billie Eilish, Victoria Monét, boygenius, Phoebe Bridgers and SZA. Half of those women are lesbians or bi or queer identified women.

That’s how much music has changed and the climate around music has changed. At the Grammys with Joni Mitchell was her friend and fellow performer Brandi Carlile, who rocked country music when she came out.

Mitchell sang her signature song, “Both Sides Now,” which now, when she is 80 and having survived a life-threatening health crisis a few years ago, has taken on a whole new meaning than when she wrote it at 24 — the same age Chapman was when she wrote “Fast Car.”

Many people have written about Tracy Chapman since that performance at the Grammys. Everyone wanted to take ownership of her and that song. As I tweeted during the Grammys, posting a clip of her performance, “This song was always a queer anthem for some of us. And Tracy Chapman a queen. #GRAMMYs.”

As a lesbian — at that time partnered with writer Alice Walker — Tracy Chapman had so much resonance for young lesbians, like she was and I was. But of all the writing about Chapman post-Grammys, it was only in the queer press that I read any references to her lesbian content. Everyone else erased the lesbianism of the women in the story and of Chapman herself.

It was a keen reminder of why we need queer media and historians of queer and trans culture to make sure our lives and stories are not erased by the dominant culture. Music has so often been encoded for LGBTQ+ people — a language in which we embed our secrets and speak to each other without being outed.

“Fast Car” was a subversive track in 1988. In 2024, nearly 40 years later, Chapman, a Black lesbian folk singer, performed with Luke Combs, a straight white country music star who grew up loving that song. It’s a reminder that everyone brings their own story to music. Songs are like valentines, often telling us, as in the line from “Fast Car,” that “we belong.”