In an interview with LIFE magazine in 1963, James Baldwin said, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

Nobel laureate Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

For historically marginalized groups — Black people, LGBTQ+ people, Black LGBTQ+ people among them — the importance of written narratives, of stories that reflect and represent those groups in their own voices from the vantage point of their lived experience, cannot be overstated. This explains why preventing those narratives from being written and shared has long been a focal point of the dominant culture and society. The suppression of Black narratives is a thread that runs through U.S. history. In the U.S. even teaching slaves to read was a crime. Stories by LGBTQ+ people have been banned for generations — deemed “obscene” or “perverse” and LGBTQ+ people pathologized.

The suppression of stories by and about these two groups from American life and culture has resulted in displacement and erasure: If you can’t read about these people and their lives, do they even exist? How many LGBTQ+ people lived their whole lives not knowing there were others like them? The plan of the dominant white and straight and cis society was to maintain white supremacy and heteronormativity.

Bayard Taylor’s novel “Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania,” first serialized in “The Atlantic” in 1870, was described as a story of a young man in rural Pennsylvania and “the troubles which arise from the want of a broader education and higher culture.” The story is believed to be based on the poets Fitz-Greene Halleck and Joseph Rodman Drake, and since the late 20th century has been called America’s first gay novel, its hero described as “shy and sensitive” and “wanting of true manliness.”

Taylor, a prolific writer, was not gay, but dedicated this novel (he wrote others) to those “who believe in the truth and tenderness of man’s love for man, as of man’s love for woman.” The novel tells the story of a young farmer, Joseph Aster, who marries a wealthy woman before falling in love with his close friend. The tale also has a political element as Joseph’s lover, Philip, argues for the rights of people “who cannot shape themselves according to the commonplace pattern of society.”

How many other gay writings, written by gay and lesbian people, were suppressed in the U.S. prior to 1870? In 1649 in Plymouth Colony, Sarah White Norman and Mary Vincent Hammon were prosecuted for “lewd behavior with each other upon a bed”; their trial documents are the only known record of sex between female English colonists in North America during the 17th century. If the crime was on the books in the 17th century, were there writings about it as well?

For Black Americans, the story of Black narratives is inextricably bound to slavery. From the early 17th century, as “The 1619 Project” explains, this was part of maintaining slavery. Enforced illiteracy was law. Between 1740 and 1867, anti-literacy laws in the U.S. prohibited enslaved, and sometimes free, Black Americans from learning to read or write.

For example, in 1831 and 1832, statutes were passed in Virginia prohibiting meetings to teach free Black people to read or write and instituting a fine of $100 for teaching enslaved Black people. In Alabama, the fine was $250 to $500 as it was in Mississippi.

At this time, “Harper’s Weekly” published an article that stated “the alphabet is an abolitionist. If you would keep a people enslaved, refuse to teach them to read.”

There was fear that writing could make it easier for slaves to plan insurrections and mass escapes. Literacy meant freedom. Frederick Douglass was taught the alphabet in secret when he was 12 by his master’s wife, Sophia Auld. In “Blessings of Liberty and Education,” Douglass said, “Education means emancipation. It means light and liberty. It means the uplifting of the soul of man into the glorious light of truth, the light by which men can only be made free.”

A century later, renowned Black lesbian poet, scholar and essayist, Audre Lorde said, “I write for those women who do not speak, for those who do not have a voice because they were so terrified, because we are taught to respect fear more than ourselves. We’ve been taught that silence would save us, but it won’t.”

Lorde wrote often about internalized suppression and oppression. But the power of external forces to silence historically marginalized people remains a powerful threat from the dominant society and culture. The GOP has made banning books with LGBTQ+ and Black content a focal point of their public policy in recent years.

Baldwin explained succinctly why the GOP would focus on banning books by Black and LGBTQ+ people. As he wrote in “The Devil Finds Work,” “The victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he or she has become a threat.”

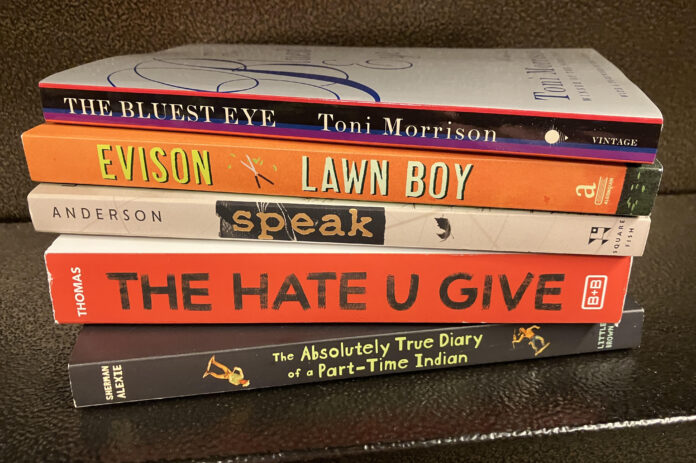

The GOP most definitely perceives Black and queer writers to be a threat. The American Library Association (ALA) says that books about LGBTQ+ and Black people were among the most challenged books in 2021 and 2022.

In October 2023, The Intercept investigated how Scholastic Books makes it easy to ban Black and LGBTQ+ books.

“Caving to the far right, the children’s book giant lets school book fairs exclude diverse titles en masse.”

The Intercept reported, “Reactionary demands to censor books on topics ranging from Black history to LGBTQ+ existence have been abetted by the timid acquiescence of school districts, superintendents, and others in educational leadership. Now, Scholastic, the world’s largest children’s book publisher, has joined the constellation of parties tacitly aiding the GOP’s suppressive agenda.”

A billion-dollar multinational corporation that hosts 120,000 book fairs in the U.S. each year. Books on Black identity, picture books with LGBTQ+ characters, stories of Indigenous history and migration, among others, have been grouped together in a collection under the title “Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice,” which appears to highlight diversity, yet also marginalizes it. School officials can — and do — opt to exclude the entire section from their schools’ book fairs.

According to a report from PEN America, in the 2022 to 2023 school year there were 3,362 recorded instances of book bans in U.S. public school classrooms and libraries.

“Authors whose books are targeted are most frequently female, people of color, and/or LGBTQ+ individuals,” the report noted.

In a statement about the issue, Scholastic said in part: “Because Scholastic Book Fairs are invited into schools, where books can be purchased by kids on their own, these laws create an almost impossible dilemma….back away from these titles or risk making teachers, librarians, and volunteers vulnerable to being fired, sued, or prosecuted.”

Thus is the imperiled nature of Black and LGBTQ+ narratives in 2024, during Black History Month: Yet another layer of suppression of the most marginalized of American voices. On MSNBC Feb. 3, Ali Velshi highlighted the banning of books and the issues in Philadelphia — the birthplace of both liberty and libraries. Velshi referenced the extremist group Moms for Liberty and their July 4th weekend conference in Philadelphia — and their focus on book bans.

Velshi also interviewed Visit Philadelphia’s CEO Angela Val, who said, “We get to know one another by reading stories.” Val explained how more than 30 states in the U.S. have banned certain fiction and non-fiction books by Black authors. She said this Black History Month, multiple organizations across Philadelphia along with Visit Philadelphia, the official tourism board, are making those books accessible with book boxes throughout the city.

The Free Library of Philadelphia, Visit Philadelphia and Little Free Libraries — a nonprofit that creates and distributes free book-sharing boxes — have joined together to create “Little Free(dom) Libraries.” The brightly decorated boxes have been placed in 13 locations throughout Philadelphia, from the Betsy Ross House to the Eastern State Penitentiary. Val says, “Black history is also American history. And these stories are worth telling and sharing.”

As lesbian revolutionary Angela Davis wrote, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.”

The Little Free(dom) Libraries can be found throughout the city at the following locations:

1. Betsy Ross House, 239 Arch Street

2. Columbia North YMCA, 1400 N. Broad Street

3. Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, 2027 Fairmount Avenue

4. Faheem’s Hands of Precision, 2100 S. 20th Street

5. Frankford Community Development Corporation, 4667 Paul Street

6. Franklin Square, 200 N. 6th Street

7. Historic Germantown, 5501 Germantown Avenue

8. Johnson House Historic Site, 6306 Germantown Avenue

9. Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, 419 S. 6th Street

10. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway

11. The Independence Visitor Center, 599 Market Street

12. The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, 300 S. Broad Street

13. South Street Street Off Center, 407 South Street