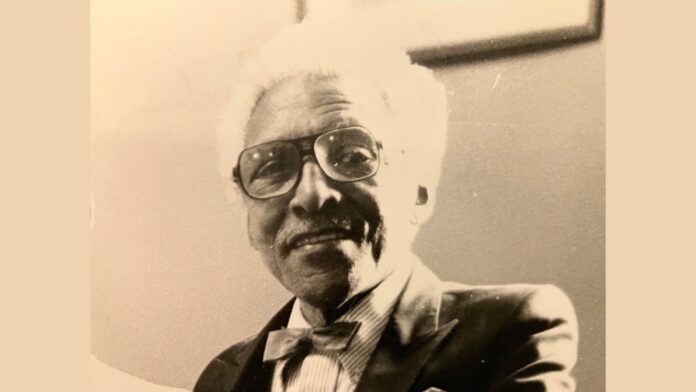

In March 1986, Bayard Rustin gave the keynote speech at the fifth anniversary celebration of Black and White Men Together (BWMT) Philadelphia, a group dedicated to bringing together gay men of various ethnicities. The veteran civil rights leader’s career spanned more than 50 years and included organizing the 1963 March on Washington as well as supporting trade unionism, pacifism and gay rights causes and organizations like BWMT. To the crowd that gathered at the anniversary celebration, Rustin had a key message: visibility of the gay community is crucial.

“One chief obstacle to the freedom of gay people,” Rustin said, “is gays in the closet, because if one does not stand up for himself, other people will never be moved to stand up for one.”

“Every gay person is needed out here to fight politically, and therefore our objective must be to try to get them out of closets,” Rustin continued. “We must try to get all people who have any prominence at all publicly to declare their gayness with a sense of humility and for us to applaud them for their ability to be totally honest and open.”

Along with his keynote speech at the event, Rustin also took part in a panel discussion titled “Liberty and Justice for All: How Do We Achieve It?” with State Rep. Babette Josephs, City Councilmember Ed Schwartz and City Commissioner Marian Tasco. Much as BWMT was founded to lessen the divisions between gay men of different ethnicities, Rustin addressed how divisions between all people can lead to intolerance.

“The minute I say me and my kind are like this, but those people are like that, that is the gravest of all sins,” he said. “If you are like that and I am like this, ultimately there is nothing on earth I cannot do to you. Ultimately I can make a lampshade out of your skin, and ultimately I can burn you at the stake, or ultimately I can burn you in ovens.”

In order to prevent such acts of inhumanity from happening, Rustin declared that the gay community must fight for all people.

“The most inconsistent thing I can think of is a gay person who is an anti-Semite or like many of the gays in New York who don’t want blacks coming in their bars.

“The main thing is that we cannot fight for the rights of any one segment — gays first — unless we are really able to fight the new mood in the U.S., unless we are ready to fight for a radicalization of this society. Do you really think it’s possible for gays to get their rights in a society where people take adequate school lunches from school children?”

Rustin, who was born in 1912 in West Chester, began fighting for civil rights at a young age and endured attacks from his colleagues in the movement for his radicalism and his homosexuality. However, he was able to make peace with many of his critics, such as labor leader A. Philip Randolph, and often worked with them to further the movement. When Rustin was attacked in 1963 by then-Senator Strom Thurmond, who called for his removal from organizing the March on Washington due to his homosexuality, his supporters in the movement “stood up 200% behind me,” he said.

Rustin also spoke to the BWMT crowd about the right wing’s weaponization of language against the gay community, citing terms such as “the home,” “the family,” and “values that must be retained.” On the latter, he said “Values, like time, are only values in the process of change.” He also addressed the value in supporting groups at the fringes of society, saying “always select to know the truth that group which is most mistreated.”

During a question and answer session at the event, Rustin posited that the gay community needed help from the general public in fighting off AIDS-related stigma, and that gay people needed “the majority of the American people to vote for the kinds of people who take positions that are intelligent.”

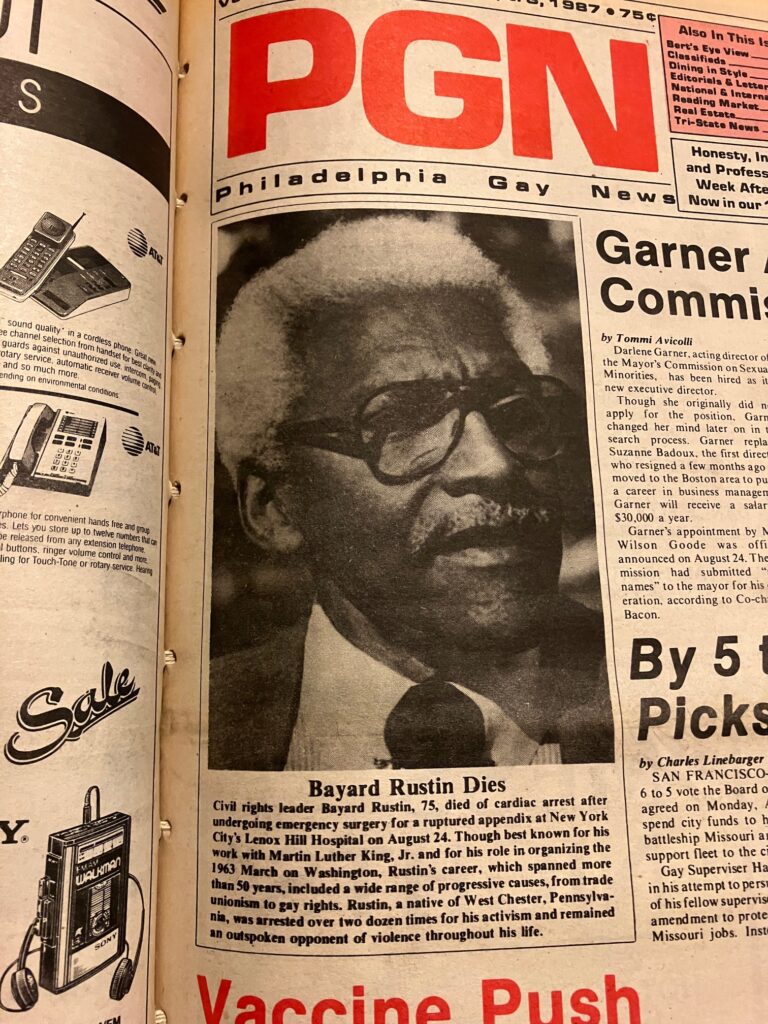

The year after he spoke at BWMT, Rustin passed away at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York at the age of 75. His work in the civil rights and antiwar movements featured heavily in obituaries, but many omitted his work in the gay community as well as his homosexuality.

“Given his strong feelings about being out of the closet,” PGN Editor Tommi Avicolli Mecca wrote at the time, “it was unconscionable that both the Inquirer and the Daily News, in their coverage of Rustin’s death, merely reprinted an AP story that did not mention that he was an openly gay man. The Inquirer also failed to mention it in a follow-up story the next day, which was written by a staff writer. An exemplary role model for all gays and lesbians, and black gay men in particular, was condemned to the closet in his obituary notices in many newspapers.”

Over time, Rustin’s homosexuality and contributions to the gay community did find their place in newspapers, books and films, including most recently in George C. Wolfe’s 2023 biopic “Rustin,” starring Colman Domingo as the figurehead. They paint a picture of a man who lived his life openly and worked tirelessly in the name of equality.

“I don’t believe that we will ever completely find total human rights,” Rustin told the BWMT audience in 1986. “But we are commanded never to stop trying to achieve it.”