There is an intriguing concept of reconciling with ghosts at the heart of “All of Us Strangers,” which is set to hit theaters in Philadelphia next month. But in telling two parallel stories, the film only half works. Out gay writer/director Andrew Haigh’s uneven metaphysical romance addresses themes of love, grief, loneliness, trauma and memory, but the film provides more ambiguity than insight. Despite a suitably elegiac mood, this film feels undercooked — when it isn’t too on the nose.

The story, adapted from Taichi Yamada’s novel, has Adam (out gay actor Andrew Scott), a screenwriter in London meeting Harry (Paul Mescal) one night in a London apartment building where they seem to be the only two residents. Their lingering handshake suggests an attraction, but Harry is a bit messy, and Adam initially rejects his advances.

Adam is working on a screenplay about his parents, set in 1987. After looking through old photos for inspiration, he takes a train back to his childhood home. While wandering around, he sees his young self (Carter John Grout) in the window of the house, and later discovers his parents (Jamie Bell and Claire Foy) are living there — and they are the same age they were when Adam was 12 and they perished in a car crash. As such, Adam sees dead people and talks with them.

Back in London, Adam does not discuss this encounter with Harry when they meet up, smoke weed, and talk about whether they prefer the word “queer” or “gay.” They soon kiss and have sex, initiating a relationship.

But everything feels a bit strange. Adam and Harry are perhaps connecting because they are the only two people/gay men in the building. Adam’s meetings with his parents may, in fact, be fever dreams — after all, he is often checked for a temperature, and he does trip out on ketamine in one sequence, where he has strange visions.

Haigh provides many clues, but too few answers. “All of Us Strangers” is a slow, contemplative drama that invites viewers to puzzle out the truth. But it is also easy to resist the magical realism, as Adam is frequently waking from sleep, blurring his fantasy and reality. A montage of Adam and Harry enjoying a cozy domesticity may just be a drug-induced hallucination.

One place Haigh isn’t subtle is in the film’s soundtrack. When Harry meets Adam, he quotes a line from Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “The Power of Love.” (The video is paused on Adam’s TV.) Adam’s parents sing “You Were Always on My Mind,” by the Pet Shop Boys to him as they trim a Christmas tree, and Patsy Cline’s “If I Could See the World (Through a Child’s Eyes)” plays when Adam has a meal with his parents. Likewise, the film’s background score, by Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch, is also a mix of ethereal and ominous music designed to make sure viewers know what to feel.

The early scenes between Adam and Harry nicely capture an emotional intimacy, but a later scene where Adam hopes to introduce Harry to his parents, suggests Adam may suffer from some mental illness, an idea that goes unexplored.

The scenes with Adam and his parents are also frustrating. During a visit with his mom, Adam comes out to her, and she worries that he will have a “sad, lonely life.” (From what the film shows, he does.) Adam assures her things have improved for gay men in the past 35 years, but his point is made thrice. Adam also chats with his father, who accepts him, even as he raises the gay cliché that Adam was unathletic. Their conversation works towards healing, as Adam admits that he “muddled through” his life and is comfortable with his sexuality.

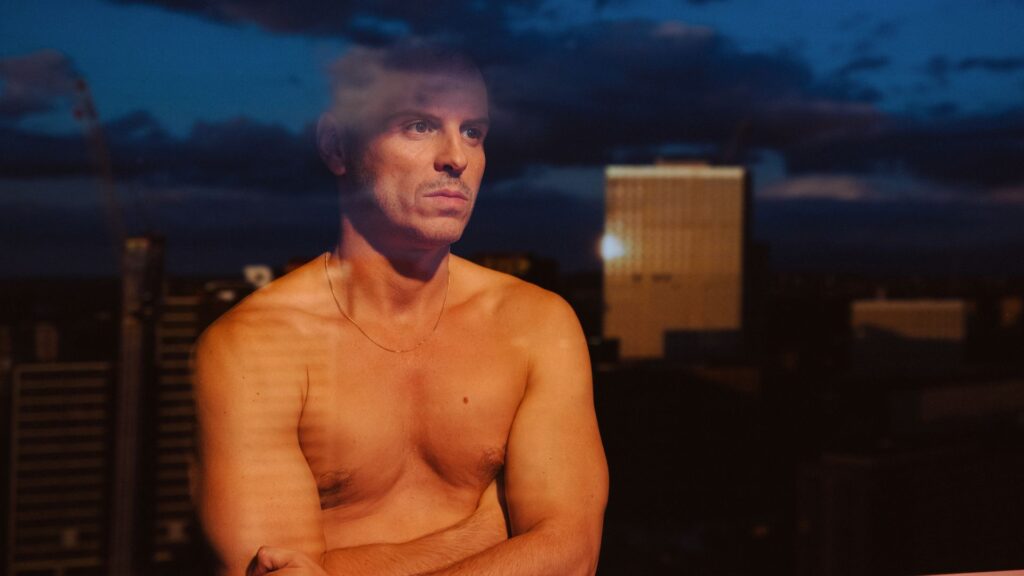

To the film’s credit, Andrew Scott delivers a very sensitive, internal performance especially when he shows Adam’s vulnerability. His desire to love and be loved comes through during his thoughtful moments, such as a chat he has lying naked with Harry after sex. In contrast, numerous shots of Adam alone and staring off into space — which are supposed to reveal how he processes his emotions and his broken interiority — just come across as overly arty.

Alas, Paul Mescal feels curiously underused as Harry, but his character is underdeveloped. A scene late in the film featuring Harry is best as it will prompt viewers to recalibrate what they may have seen or believed. It is certainly the film’s most provocative moment.

Less interesting is how Harry slightly resembles Adam’s father. The film flirts with oedipal ideas — Adam’s first encounter with his dad plays like a hookup, and a scene featuring the adult Adam sharing a bed with his late parents is awkward. But these ideas just hang there.

“All of Us Strangers” will have its admirers, but the film is more ambitious than good. Despite some strong elements, it lacks the emotional power it strives for. The tone is all heartache and loss, but the melancholy and longing somehow feels too muted and subdued.