“Who needs decorations in a place like this?” exclaimed Shelley Hedlund, a queer parent and local artist, as she gestured toward the colorful books, jewelry, art, Pride gear, and quirky chandeliers that adorn Giovanni’s Room — the nation’s oldest, still-operating LGBTQ+ bookstore. Queer people in the area tend to be familiar with this hub, which is located in the heart of Philadelphia’s Gayborhood and serves as a community resource, sanctuary and gathering place.

But on Tuesday, Dec. 12, Hedlund wasn’t at the store for a book club or holiday party. She was there to attend the wedding of Pauline Gnesin and Sage Milo.

“What better way to celebrate this wonderfully unique space than to be able to host such a beautiful moment in someone’s life?” said Christopher Cirillo, who manages the store, which is formally known as Philly AIDS Thrift @ Giovanni’s Room. “To be able to celebrate queer love in a store that was built with the love of so many that came before us is probably one of the most beautiful things I can think of.”

Cirillo said the wedding is a first for the store, but Gnesin and Milo aren’t alone in their feelings of deep connection to Giovanni’s Room. Patrons tell him stories about life-changing visits and meet-cutes. He also underlined that people have historically come to the store “when they were grappling with their identity, looking for an understanding, compassionate ear, or just needed a place where they could be seen for who they are.”

“It’s the first queer bookstore I ever visited,” he said, explaining that the store’s evolution over the 30 years since that visit reflects how the community has grown over time. That Giovanni’s Room has survived 50 years is a testament to “how important this place is” to Philadelphians, added Cirillo, who has spent his career working with and at queer bookstores both as an employee and as a distributor. “It is not lost on me that the stores I previously worked at no longer exist.”

When the couple talked about holding the wedding at Giovanni’s Room, they couldn’t let go of the idea. “It’s multigenerational. You don’t have to be 18 or 21 to go there. Anyone can go there,” Gnesin said, underlining that the store has a children’s section and a large selection of used books which increases accessibility. “It’s also a sober space, which is great.”

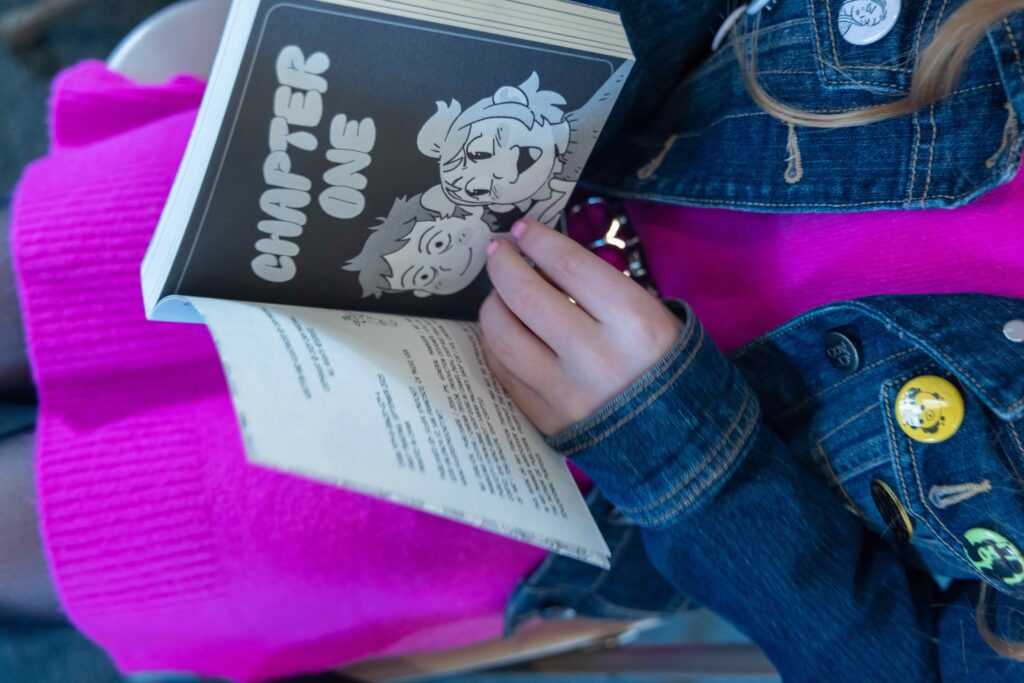

“We want our guests to buy books or other merchandise,” said Gnesin, who asked loved ones to browse before and after the event instead of bringing gifts. “This is both so they can donate to the store but also hopefully carry some parts of queer literature — queer history — into their own homes, communities, schools — spread it around.”

As a teen selected vintage CDs, another guest flipped through a cookbook nearby. Most attendees found something to bring home. An eclectic playlist set a loving and playful tone with feminist folk songs, kitschy classics and meaningful ballads.

During the ceremony, guests sat in folding chairs next to the fireplace in the second floor parlor as a baby slept in a stroller in the next room. Some had traveled from other states, other countries, and even other continents. Milo’s sister live-streamed the event for those who couldn’t make it. Teens lined the back row as a singular unit. Space was limited, and some friends ducked into the “Adults Only” section to find a spot below the store’s penis banner.

“The cis, straight people who are invited to this event are massively outnumbered by trans and queer people,” said Milo, “which is never the case at weddings and often not at other events too.”

“Maybe it’s in the queer DNA to be self-sufficient, to think you have to do all things for yourself,” said Linnea Carlson DeRoche, who is a queer parent, theater professional and teacher, as they welcomed the group. “But of course, we need to work together. We need one another. There are times when we need to do the holding and other times when we need to be held.”

Loved ones spoke eloquently about their appreciation for the couple’s desire and ability to show up tangibly for their families and community members this way. Some read original poems and favorite quotes. As they listened, Gnesin cuddled Milo, who is nonbinary and transmasculine, in a window seat that faces 12th Street. A trans pride flag waved behind them in the wind.

Gnesin said of her identity, “I relate to the long, proud many-gendered tradition of queer motherhood — of making family, of making home, of making ends meet, of making do. I identify with queer femininity — which means muscle and cushion, nourishing and protective with teeth.”

Their marriage certificate, designed by a friend, Shraddha Chatterjee, includes an illustrated shipwreck, referring to the house they share together — affectionately referred to as Shipwreck Home. The family hopes it can provide a “landing spot — even a home — to anyone who finds us and needs it,” Milo said. This mirrors the mission of Giovanni’s Room, which often welcomes people who are in need of refuge.

Milo became what they referred to as a third parent to Gnesin’s children. The pair co-parent with Gnesin’s former partner, Shawn Byrd, who is the couple’s close friend and housemate. The nontraditional family welcomed a third child as an unofficial foster two years ago.

Milo, who until recently taught courses — including queer history — at Villanova, supported that child, who is a college student, when his family of origin became estranged. Milo left academia for a job in healthcare and to study nursing, a choice informed by a desire to provide trans-competent care. Gnesin has a long history of working with young people — including as a homeschooling facilitator, which allowed her to introduce queer history to her children and students.

“We still learn together as a community, and how much the young people teach us too, I think, is another big part of learning in an intergenerational way,” Gnesin said.

The two never imagined this life could be possible.

“We didn’t have anyone we could look at who represented possibilities for what life could become as queer adults,” said Milo, who is from Israel and lacked language for their identity due to the gendered constraints of spoken Hebrew.

Gnesin, who grew up in North Jersey, discovered the back pages of the Village Voice as a source for queer content — but these were personal ads that often fetishized and sexualized queerness rather than show more mundane ideas of what it could mean to be a queer adult.

Milo, who is 43, and Gnesin, who is 47, are sometimes called queer elders because many queer people from older generations haven’t lived long enough to fill those roles. Giovanni’s Room, founded in 1973, has comforted the community, linked people together, and provided respite throughout decades of shifting challenges and uncertainties.

Before reading vows, the couple addressed their guests. Gnesin looked up at the kids in the room — including multiple queer youth — to say, “My hope for you is that you do not have to be queer elders in your 40s. We will still be here to cheer you on.”