The Leonard Bernstein biopic, “Maestro,” opening Dec. 1 in area theaters and available on Netflix Dec. 20, is as atonal as some of the composer’s music. Shifting from black and white to color, jumping across time, and featuring long passages from some of Bernstein’s works — but only mentioning career highlights, like his Concerts for Young People — this biopic, directed, co-written (with Josh Singer) and starring Bradley Cooper in the title role, is all over the place.

That is not necessarily a bad approach to the life story of a man as brilliant and as complicated as Bernstein. This drama purposely focuses on Bernstein’s relationships with Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan) while also addressing his career and his sexuality. But the parts are greater than the whole. (Cooper seems to have taken cue from the uninspiring 2021 documentary, “Bernstein’s Wall,” which traverses much of some of the same territory.)

The opening scene has an aged Bernstein tickling the ivories of a piano as a film crew documents him. Flash back — and into black and white — as Bernstein receives the call that will change his life: he is asked to conduct the New York Philharmonic after guest conductor Bruno Walter fell ill. In a fabulous sequence, shot in overhead, Bernstein goes down the stairs through the hallways and right out onto the stage. (Cooper loves this gimmick so much, he uses it again in another scene).

At a party, given by his sister, Shirley (Sarah Silverman), Bernstein meets Felicia, an actress, and the two of them hit it off. She takes him to a theater where they perform a scene and their courtship includes sweet moments — including a musical sequence from his show “On the Town,” where he performs a kind of seduction, kissing Felicia, but being pulled away by male dancers. It’s rather symbolic.

“Maestro” is best in moments like these when it showcases Bernstein’s music, which is layered over many scenes. One absolute showstopper occurs late in the film, with him conducting his work, “Mass,” in a church. It is a fantastic performance that shows Bernstein at his most brilliant and passionate. But the scenes of him off stage, which also show him being brilliant and passionate, fail to generate the same enthralling emotion.

Bernstein is a genius, and Cooper conveys this by explaining that he is an extrovert who has a grand inner life. “Maestro” shows Bernstein getting excited working on projects, as he proudly announces finishing the draft of a composition. He does not like to be alone, keeping the bathroom door open, so he always has company. And he battles depression, in part because he loves men, and can’t really be with them. His relationship with clarinetist David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer) is given too little screen time, but in the few brief scenes addressing this, there is a wistfulness about the impossibility of their relationship that is affecting.

Other scenes that depict Bernstein’s sexuality include a kiss he has in a hallway where Felicia is spying nearby, as well as a scene where Bernstein addresses rumors his daughter Jamie (Maya Hawke) hears about her father’s sexuality. The film frequently examines this issue from Felicia’s point of view, as when the camera zooms in on her steely look during a musical performance as Bernstein holds a male companion’s hand, or takes him to task for his behavior.

Felicia is as formidable a character as Bernstein, and as the story pivots to her in its later half, it gets more interesting. A fight she has with her husband is a dramatic highlight (and not just because something dramatic happens). When Bernstein tries to change the subject, Felicia retorts, “This is about you, so you should love it,” puncturing his inflated ego, and an example of the film’s on-the-nose dialogue.

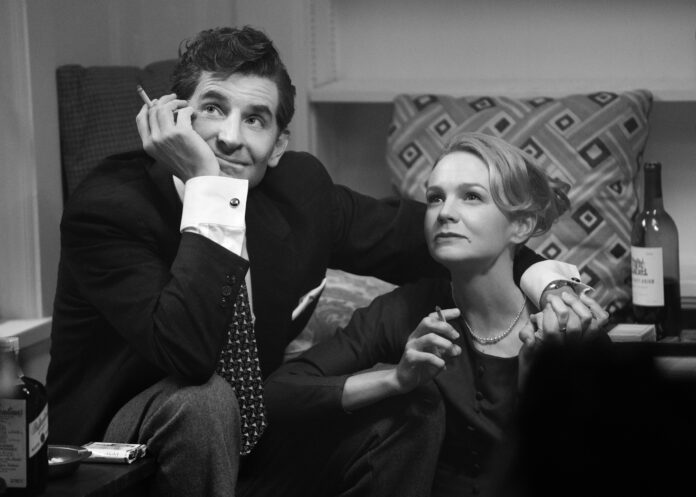

Bernstein needs to be the center of attention in every scene, and “Maestro” gets that right. The musician cannot walk into a room without taking it over, such as when he teaches a student how to conduct. Cooper’s performance, which gets Bernstein’s voice and look right, as well as his constant smoking, is aggressively outsized. It may be true to life, as scenes in the film mirror footage of Bernstein, but however convincing Cooper is, he never quite captures Bernstein’s magical, mercurial, magnetic quality. It is a strenuous performance that comes off largely as mimicry.

However, Carey Mulligan is superb as Felicia, not just in her fight scenes, or her long-suffering moments with Bernstein where she casts a disapproving glance. Mulligan has some terrific speeches, such as one about meeting a man for lunch that did not turn out as expected or listening to a story about her husband’s antics at a wedding. Mulligan expresses so much with her eyes that she becomes the real hero of “Maestro.” (Cooper graciously gives her top billing).

But despite its many fine elements, the film feels uneven, unfocused and unsatisfying. The flashback narrative that bookends the story and the use of black and white both seem superfluous. And Cooper cannot resist winking at the audience with a needle drop of R.E.M.’s song, “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine)” — but he should have. The editing also feels jagged at times.

“Maestro” may be a loving tribute to Bernstein, but this disappointing film comes off as self-serving Oscar bait. At least the music is great.