Kathryn Morris died last week. For those close to her, it was both a shock and expected. She’d been hospitalized for several weeks after an acute medical crisis and had been moved to a rehabilitation center ten days before her death to help her regain strength before going home.

For the small circle of close friends and family left to mourn her passing, Kathy’s death is a gutting tragedy that exemplifies all that can go wrong in a society that too often neglects its most vulnerable members to death.

For several years, I had been Kathy’s patient advocate, trying to get her the kind of health and welfare services she needed in her red state that had failed her multiple times.

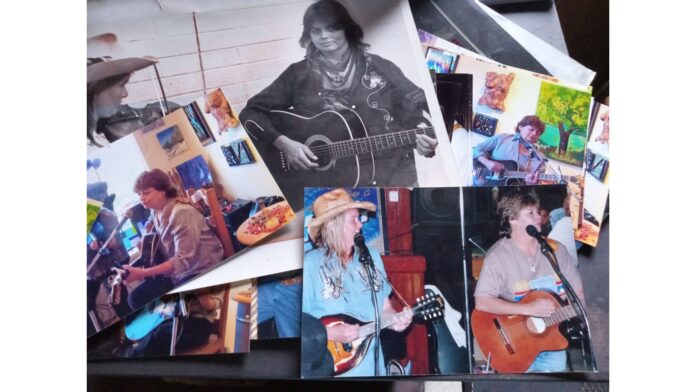

Years ago, Kathy was a singer. She was beautiful, with a sultry and mysterious air about her. She’d been partnered with a close friend of mine decades ago when they were both 20something artists living in Las Vegas.

But for the last decade or more of her life, Kathy no longer sang. She battled two autoimmune diseases common to women — lupus and Addison’s disease. These diseases hadn’t killed her, but they had limited her life in many ways. And they had made her dependent on painkillers.

According to the U.S. Pain Foundation, chronic pain is a crisis in America that no one talks about. Chronic pain has devastating consequences on function, quality of life and mental health.

Concomitantly, we don’t talk about the crisis that runs parallel to it: opioid addiction. Sure, the GOP talks about fentanyl coming across the border in states like where Kathy lived. But they don’t talk about the human toll in pain and suffering that millions of Americans who are self-medicating experience.

According to the American Medical Association (AMA), an estimated 3% to 19% of people who take prescription pain medications develop an addiction to them. People misusing opioids may try to switch from prescription painkillers to heroin when it is more easily available.

As anyone who lives with chronic pain knows, there can be a time where the line gets blurred and then crossed between taking medication as prescribed and taking it as needed to dull not just the physical pain, but the psychic pain that comes with not having control over one’s own body.

For Kathy, that line blurred and then disappeared altogether. The pain controlled her life and she tried to control it. It was a vicious cycle that the people who loved her tried to help her out of, but couldn’t. Kathy tried to help herself out of it, but couldn’t.

I spoke with Kathy a few times in the last weeks of her life and each time, she was weaker. I could tell time was running out. I was negotiating with human resources in her state to get her what she needed for when she finally left the rehab place and returned home to her trailer and her music and the little dog she adored.

It’s hard to accept that that will never happen now. It’s hard to accept that this woman who had once brought people so much pleasure with her voice and her guitar was now silenced, having lost her voice and her agency long ago.

I want to tell Kathy’s story because we need to tell all our stories. Not just the celebrity stories and the tales of immense LGBTQ+ accomplishments, but the other stories — the stories of promise derailed and hope deferred and lives tangled up in a complexity of homophobia and discrimination and isolating pain and suffering and loss. For years, Kathy mourned her lost life as the people who loved her now mourn hers.

LGBTQ+ people are much more susceptible to substance abuse than their cis-het peers. Statistics show that LGBTQ+ adults are more than twice as likely as their heterosexual counterparts to use illicit drugs and almost twice as likely to suffer from a substance use disorder.

Despite polls that show more tolerance for LGBTQ+ people in the U.S., almost all LGBTQ+ people face homophobia, transphobia and discrimination from strangers, acquaintances and even friends and family. They also face the constant threat of workplace harassment, bullying and even hate crimes. As I have reported before, these things can lead to depression, anxiety and self-medicating.

I only knew Kathy after. After she’d been worn down and worn out by fighting to just maintain her life. The photos of her days as a singer show a very different person — one full of energy and engagement as she performed.

In the last photo I saw of her just a week before her death, Kathy is frail and vulnerable and looking much older than she was.

The people who were closest to Kathy — her friends Martha and Valerie, her friend Pat who used to perform with her, her brother Donnie who drove two hours each way most days just to visit her in the hospital — those people are grieving their loss. Anchored for so long by caring for Kathy, they are now unmoored with nothing to tether them to their memories or even to each other.

Kathy imprinted the people who loved her. She imprinted me in the time I knew her. I wanted to tell her story because our collective LGBTQ+ history is more than the history of the obvious successes. It is also the history of what can happen to queer and trans people for whom the relentlessness of homophobia and transphobia is too much — people for whom the pain of that trauma causes or exacerbates other trauma, as it did for Kathy.

The LGBTQ+ party line is “it gets better.” But for many LGBTQ+ people, it never gets better. A problematic adolescence, a scalding coming out, an inability to find one’s footing in a cis-het society in which there is still largely no place for us — that can lead to late nights at the bars and savage dawns that never return people to any kind of normalcy.

As we celebrate LGBT History Month, let’s not forget that part of why we celebrate our successes is because there are so many people who have been failed by our homophobic and transphobic society and we believe seeing those successes will be the impetus to survive and thrive and make a life that works — or is at least bearable.

It’s important that we not forget the stories close to home — the personal histories of the people we cherish.

A legacy is revealed in the lives of queer and trans people we love, who we consider our chosen family.

Kathy Morris leaves a coterie of grieving loved ones. She leaves photographs and music and mementoes of a life that was once filled with excitement and promise and the euphoric joy of performing.

Kathy Morris leaves a history that ends in tragedy, but is more than tragedy, and must not be reduced to mere tragedy. Kathy fought for a pain-free life and didn’t get it. Kathy’s community failed her. Society failed her. Our memory of Kathy and all the many LGBTQ+ people we have known and loved and lost to pain and how they tried to treat it — that memory — that seared and unforgettable memory — that must not fail her.