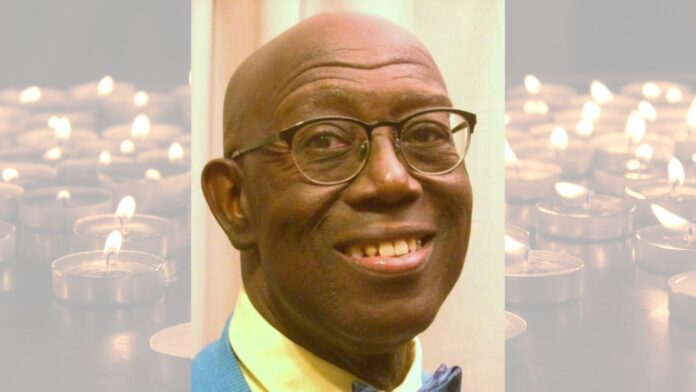

Steven “Stevie” Martin-Chester, activist, long-time leader of the Philadelphia chapter of Men of All Colors Together (MACT) and member of Whosoever Metropolitan Community Church, died Aug. 2 at the age of 73. He was married to Arthur “Art” Martin-Chester, who died in 2018. Stevie originally hailed from Connecticut, and moved to Norristown with Art in the early 1990s. The couple actively fought against racism in Philly’s LGBTQ+ communities for more than two decades.

“Stevie was — I hate to use the cliché larger than life — but he had that sort of presence around people,” said Gary Hines, who met Stevie when he joined MACT in 1995. “Stevie was an in-charge, take-charge kind of guy. I immediately connected with him just because he had the kind of personality that drew you in.”

MACT-Philly was established in 1981 as one of 10 chapters of the National Association of Black and White Men Together, an advocacy group based in San Francisco that works toward racial equality in LGBTQ+ communities. Stevie and Art co-chaired the membership committee of MACT-Philly in the 1990s, where they welcomed newcomers and brought them up to speed about the mission of the group.

For MACT-Philly’s yearly anniversary celebrations, Stevie created an event called “theater of understanding,” which manifested as a workshop “to bridge together some of the disparate groups in the LGBT community,” Hines said. For each “theater of understanding,” different guests would come to speak, including politicians, faith leaders and local advocates. The “theater of understanding” became a key component of MACT-Philly.

Stevie also made an effort to foster relationships with other local LGBTQ+ organizations, including Latinx groups, Asian groups and the leather community to perpetuate MACT’s mission of countering discrimination in Philly’s LGBTQ+ communities, according to Hines.

In 2016, when the former owner of the bar iCandy was caught on tape using a racial slur, it precipitated a hearing led by the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations (PCHR) to give LGBTQ+ community members a forum to discuss instances of racism in Gayborhood bars and nonprofits. PCHR then required certain bar owners and nonprofit staff to participate in training in Philadelphia’s Fair Practices Ordinance and implicit bias.

“That one incident in 2016 sort of pulled MACT into the city-wide spotlight,” Hines said. “They wanted to have some dialogue with bar owners, with restaurant owners in the Gayborhood to address some of the discrimination they had been hearing about.”

Beyond their advocacy work, MACT members engaged in social activities. Hines fondly remembers Stevie’s lighthearted, jocular personality on group trips that MACT organized, and a shared love of house music. When MACT members went out to clubs, “[Stevie] would call my attention to different DJs and dance music,” Hines said. “He was just a lot of fun to be around.”

Tyrone Harvey met Stevie in 1994 when he became involved in MACT-Philly, at a point in his life when he was on a path to self-discovery and self-acceptance as a gay man. Stevie supported Harvey by helping him through the process of finding himself and by introducing him to other aspects of the gay community in Philly, including Whosoever Metropolitan Community Church (MCC).

“Stevie was more of a gay mentor to me, but at the same time because I became a member of Men of All Colors Together and then the National Association of Black and White Men Together, Stevie became that support,” Harvey said. “He was that encourager, that motivator, that person that said, ‘you’re okay; you’re going to be okay; there’s nothing wrong with it, and whatever someone has told you prior to this time, forget about it. You are on your way to becoming you.’ From that time on, I moved on with my own personal life. I made great friends and I learned a whole lot about life through Stevie.”

As a leader, Harvey remembers Stevie as an outspoken person who stayed true to himself.

“He always came forward with the truth, be it his own truth and the truth of what he was working towards,” Harvey added. “Stevie was fearless in the sense that he never had a problem being transparent with who he was and what he thought.”

Stevie and Art were also very much involved in MCC, which welcomes and advocates for members of the LGBTQ+ community. MCC “was at the forefront of advocating for gay rights even before Stonewall, said MCC pastor Rev. Jeffrey Jordan. “We’re the oldest LGBT organization in Philadelphia.”

Stevie served as lead usher at MCC, where he greeted community members with a smile and sometimes a hug, Jordan said. “Stevie was a very positive, happy, energetic, loving person,” Jordan added.

Stevie also sang in MCC’s sanctuary choir, where he would sing solos on holidays and special occasions. The song “My Cross” was among his repertoire.

Politics also pervaded Stevie and Art’s involvement in MCC; they advocated for same-sex marriage through the church and the community at large, Jordan said.

When Montgomery County Register of Wills D. Bruce Hanes was signing marriage licenses for same-sex couples in 2013 before it was legal in Pennsylvania, Stevie and Art were the 15th couple to get a license. MCC founder Troy Perry, a pioneer of the gay rights movement, came to Philadelphia in 1994 to perform holy unions on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Stevie and Art were among that group.

Another prominent aspect of their personalities as a couple, both Harvey and Jordan recounted, was the fact that Stevie and Art always dressed similarly.

“It made a statement politically that they were together despite the fact that they were two different ethnic backgrounds, two different persons, but together as one fighting for the same causes,” Harvey said.

Jordan fondly recalled that one day, Stevie and Art showed up to church dressed differently.

“Everybody in the church was concerned about the stability of their relationship because over all the years, no one had ever seen them not dressed alike,” Jordan said. “It’s hard to speak to them as individuals. They were ‘the couple,’ almost a poster child for gay relationships in Philadelphia.”

Stevie is survived by his step children and their spouses Eric Chester (Jennifer), Gregory Chester and Jennifer Hatcher (Council); grandchildren Talia, Miles, Joseph, Bishop, Maison, and Adelaide; and great granddaughter Makenna Rose Hatcher.

A memorial service will be held for Stevie on Aug. 12 at 11 a.m. at 3637 Chestnut St. in Philadelphia, in the downstairs sanctuary of the University Lutheran Church, where MCC rents a space. Family members will be there to greet guests at 10:30 a.m.