There are some fascinating queer (hi)stories in the informative new documentary, “Eldorado: Everything the Nazis Hate,” out June 28 on Netflix.

The film, directed by Benjamin Cantu — with dramatized reenactments directed by the Matt Lambert — uses the famed 1920s Berlin nightclub, dubbed “the most spectacular queer venue,” as a nexus for several case studies of its queer patrons. The individual profiles are all interesting, but shockingly, facts such as The Eldorado inspiring Christopher Isherwood’s “Cabaret,” and that Marlene Dietrich performed there, go unmentioned in the film. As such, anyone interested in the history of the venue should look elsewhere; the club is really a minor character here.

Cantu does use the Eldorado to illustrate Berlin was the “capital of sin” in the 1920s, when there were dozens of establishments catering to the burgeoning queer community. However, the freedom queer people had in the 1920s, was short-lived and replaced by decades of oppression. “Eldorado” traces the lives of its subjects over time as the Nazis rose to power and fell. The club itself closes in 1933 and, ironically, became a Nazi headquarters.

One of the most remarkable stories told in the film concerns Gottfried von Cramm, a German tennis player who was married to Lisa von Dobeneck, but had what appeared to be an open relationship after the couple moved to Berlin. Visiting the Eldorado, they took on new lovers; Gottfried took up with Manasse Herbst, a young Jewish man, and Lisa had friendships with “modern Berlin women.” These scenes are presented in dramatizations of the characters laughing and horsing around that feel unnecessary. The scenes are meant to create emotion, but feel forced. Better are the photographs and archival film clips of Gottfried, an exceptional tennis player, at the Davis Cup in 1932. Despite playing for Germany, he did not promote the Nazi agenda. The film reveals what happened to Gottfried and Manasse as the Nazis rose to power and Paragraph 175, which criminalized homosexuality, was enforced.

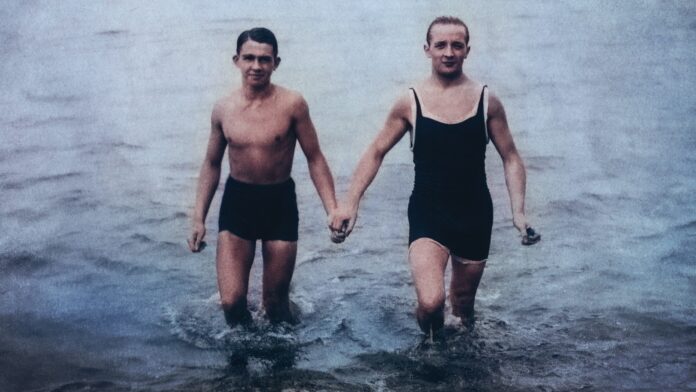

Another gay man prominently featured in the film is Walter Arlen, who spryly recounts his love for Lumpi, whom he met as a teenager and shared an intense friendship. Arlen, who is still alive, snickers recalling an erection when they took a bath together. But again, as the Nazis rose to power, Arlen and Lumpi are targeted because they are both Jewish and gay.

“Eldorado” also focuses about trans lives, including Charlotte Charlaque and Toni Ebel, two women who were said to be among the first to have reassignment surgery. They became inseparable after meeting at the Eldorado — until the Nazis forced them to separate.

Likewise, noted sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, whose Institute was a safe space for trans and queer people in Berlin, is briefly discussed as someone who patronized the Eldorado. His scientific contributions made him a target for the Nazis, who destroyed his Institute in 1933.

Posssibly the most interesting portrait in the documentary is Ernst Röhm, a high-ranking Nazi officer who was an “enemy” of Hirschfield’s. Röhm, who spent considerable time at the Eldorado, lived a double life as a stormtrooper and a gay man. He felt his friendship with Hitler would protect him, however, Röhm “didn’t maintain the necessary discretion” and is arrested, he is given the choice to shoot himself or be shot. “Eldorado” features dramatizations of Röhm at the nightclub flirting with young men in and out of drag, as well as a scene of Röhm and one of his lovers in bed when the SS arrest them. Röhm’s story is intriguing because he seems full of contradictions, but the documentary emphasizes the impact of Röhm’s story — that he created a scandal and his behavior allowed Himmler to rise to power and declare his intentions to eradicate the homosexuals (which he did).

“Eldorado” juxtaposes nightclub scenes with Hitler’s rallies as well as the rising crackdown on queer, gay, lesbian, and trans people. Neighbors were encouraged to report women who wore pants. As gay men were sent to concentration camps, they were abused, getting too little food which often caused their deaths. The persecution of homosexuals continued long after the war ended as Paragraph 175 was not repealed until 1994.

The filmmakers present all of this information with sleek, glossy nightclub scenes that work better at creating a sense of time and place than the character segment reenactments. The documentary interviews with historians, including trans historian Morgan M. Page as well as Dr. Klaus Mueller, among others, provide plenty of information to absorb, but at times it can feel too dense. The reenactments provide breathers as the filmmaker(s) cut back and forth between the profiles and the history to maintain a chronological timeline. Given how the story unfolds, the subjects in one scene may not be alive in the next, an approach that keeps viewers engaged.

“Eldorado” may be uneven and far from comprehensive, but it provides an interesting glimpse into a handful of LGBTQ lives during Weimar Germany.