The rate of book banning in U.S. school libraries has seen a 28% increase this academic year compared to last year, and Pennsylvania ranks third in terms of the volume of book bans by state, according to advocacy group PEN America.

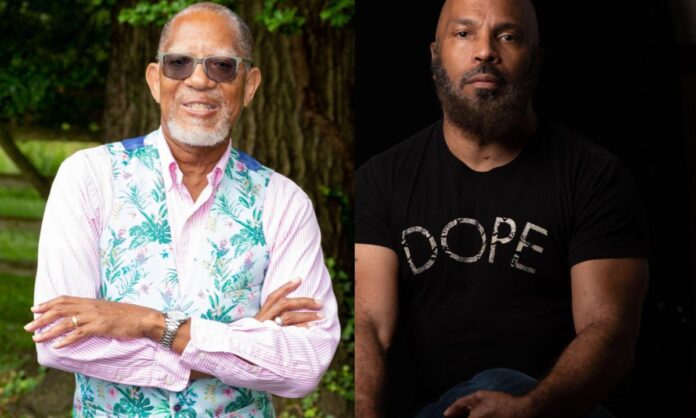

Local authors including Larry Benjamin and David Jackson Ambrose have done readings of their work and led discussions about the importance of continued reading and writing despite a hateful political climate.

Benjamin has written several LGBTQ novels, including “The Sun, The Earth & The Moon” and “Excellent Sons: A Love Story in Three Acts,” which won the 2022 Lambda Literary Award in the Gay Romance Category. Ambrose has written the books “Unlawful DISorder,” “A Blind Eye,” and “State of the Nation.”

The two authors spoke to PGN about the importance of reading and writing banned books, the LGBTQ books they loved as kids, and why they write books that challenge the status quo.

Tell me about the work that you do to advocate for reading books about marginalized identities.

Ambrose: For me, it’s just been about being there and being present, showing up and representing through the characters in my books, who are always non-mainstream, outside of what we customarily read in fiction. These are Black and Brown people, gender nonconformists, people with mental health issues, and how they are navigating through this world. So I do my advocacy in that way, which is quiet to a degree. But hopefully it gets into the hands of the people who need it most.

Benjamin: There’s another writer in Philly, a lesbian writer named Kathy Anderson. We’ve been doing some things together for National Library Week. We had done an event at A Novel Idea on Passyunk to talk about these books that are getting banned: why they’re important, exposing people to them. There’s a group called Freedom to Parent. It’s a bunch of moms who’ve gotten together and they’ve coalesced around the idea of ‘books, not bans.’ They’re really working with communities to fight these book bans.

I remember growing up, my parents never stopped me from reading, whether it was age-appropriate or not. The matter was that I read and learned about the world around myself. If I had a question, I’d come to them and they would try and answer as best they could. I didn’t grow up with this limitation, so I find it really frightening. It’s really kind of destroying our youth’s ability to think creatively and think outside of what they know.

I write because I just want to spread my message of inclusion and the fact that under our skin, we’re all the same. It’s really important for people who aren’t in the mainstream to see themselves reflected in literature, in movies, in commercials. To David’s point: [we’re writing about] people of color, people with mental illnesses, nonbinary people, all of those folks who don’t really see themselves.

Ambrose: It’s sort of a light out of the tunnel for some kids who are searching and trying to find answers to questions that they don’t have. What’s most terrifying for me is the adults and parents who are advocating for these bans or couching this in love for their children, when it seems to me to be the total opposite. If you love your child, you should want them to know everything there is about the world and not try to segregate what knowledge they obtain.

Benjamin: One of the things that’s really frightening about these bans, is that on the surface, you tend to think that a parent picked up their kid’s book that they brought them home from school, and they were offended by something so they raised a flag. But it’s not. This is really a coalition of Republican-type folks who are really organizing around banning these books, not even their kids’ books. They’re just deciding these books shouldn’t be accessible to children. They talk a lot about parents’ rights, but it’s really not being driven by the parents of these kids.

What would you say to educate people who are calling for book bans?

Ambrose: I’m sort of at a loss for what would be able to be said to parents and to organizations because I don’t think that it’s important to them. They don’t really want to know the specifics of this information. It’s just more about shutting down what is seen as different.

It was so important for me growing up — books were always my safe haven, they were always around the house. Books that people would give to my mother to read at her job — she never read them, I read them. If they had been denied to me, there was so much less information that I would have compared to what I do have now. The libraries and the schools were just a plethora of places of information for me. It’s so important, and I think that that’s important for our children to be able to have.

Benjamin: I think I would start with making “1984” by George Orwell required reading. Because when you look at everything that is happening now, this is exactly what he told us about. You start by making people invisible, you start by taking away their words so that they can’t even express an idea. That seems to be what these people are trying to do. They don’t want Black kids to understand the history of racism within this country. They don’t want gay kids to understand that they exist and that they can have a good life. So how do we do that? We just take away all of the books and the movies and stuff that show that, and then leave these kids on their own. Even if your kid isn’t a queer kid, why shouldn’t your kid read about queer kids so that when they meet a queer kid in college, or their best friend comes out to them, they know what this is and how to handle it.

One of the things I like to tell people when they ask about why I have different people in my books: I realized I was gay when I was 12. I fell in love with a Puerto Rican kid named José. I didn’t know anybody who was gay, didn’t see anything about this. And it was right around Stonewall that you first saw gay people on the cover of TIME magazine, on the news at six o’clock, all this stuff. You start to think, “oh, there is a word for me and this is who I am.” But then it became very troubling because all those images were white people. So I remember at 12, 13, 14 trying to imagine how to have a life – a Black kid, this Puerto Rican kid, when there were no gay, Black Puerto Rican people. Where did that leave me? So that created years of confusion and kind of a stress that didn’t need to exist. So if I was coming up today, I could pick up David’s book, I could pick up one of mine and say, “oh, this is who I am. I really do exist, and this is what my life could look like.

Ambrose: They’re denying this information to white children as well, which is very important. If you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it. It puts me in mind so much of book burnings in Nazi Germany and how it started with the banning of books and led to that, which then led to not only burning books, but burning people. If we don’t recall the past, we’re doomed to repeat it. So I think all children need to know these things, and it’s a disservice to deny access to that information.

Benjamin: That speaks again to, what is the point of this movement? The point is to move us back 50 or 75 years in time. So if kids don’t know this history, to your point, David, they’re going to repeat it because they think this is all there is.

What LGBTQ books did you cherish in your youth?

Ambrose: So many. I’ll only remember a few. I do remember that growing up “Dancer from the Dance” was a pivotal, pivotal book for me which meant so much. Right now I’m reading “My Government Means to Destroy Me,” which takes us back to 1980s-era New York City gay life. It’s taking me back and making me remember so many things. One of the things it’s bringing me back to was when I was coming up and searching for identity, how important it was to get from the suburbs into Philadelphia, to the places where people like me were congregating and to be able to get the PGN, which was only available in [certain] spots in Philadelphia, through restaurants and the bars and such. Going there to be able to get that was just — I was ravenous for information about people like me and that was the only place that I could get it.

Benjamin: I had read books with gay characters, but they’re always portrayed as kind of side characters or comic relief, or they’re just tragic figures. The first one that was positive that I read — it was freshman year — and I had gotten to the Penn Bookstore, and there was “The Front Runner” by Patricia Nell Warren. I’d never seen a gay book out in a display with other books. I remember buying the book and going home. My roommates were on the track team, and I spent the entire weekend and read that entire book. I went back and got her second book, I think it was “The Fancy Dancer.” It was just amazing to me that there was this gay couple in this book who had a great life, and they were out and did all of these things — all of the things that you hadn’t seen before.

The other piece was that it was Penn’s bookstore, and they were the first bookstore I had been to. I hadn’t known anything about Giovanni’s Room at that time because I was a freshman and I wasn’t from Philly. It was the first time I’d gone into a store and found gay books. I thought, “wow, this is the best thing ever; there are actually books about us.”

What would you say to a queer kid of color who goes to a school where books are being banned?

Ambrose: The World Wide Web gives you a little more freedom now so that they can access these things outside the parameters of what’s in the schools. So there is a good thing related to that, at least they can search outside of those parameters to find things.

Benjamin: I tell kids to walk down to Giovanni’s Room, they often have stands outside with dollar books. You don’t need a lot of money to get access to that literature to share them within your network. One of the other things I’ve been talking about for a while — I just met with the [executive director] of Boys & Girls Club, to have these kids write their stories. We’re actually looking at trying to find a grant and bring together some writers like me and David, and some other folks to coach these kids through sitting down and writing their own stories. Really empowering kids to understand the importance of sharing their stories. And these kids who are different, whether they are trans or non binary, or Black, or Puerto Rican, your story is very different. Only you can tell your story. So let’s sit down and work with you to start telling those stories.

Ambrose: That’s how I started writing; making comic books in school and writing little chapters and circulating them to classmates. It’s a very powerful and important place to start.

Benjamin, Ambrose, Anderson, and Laurie Greene will participate in the event Books & Beer on June 21 at 6 p.m. at Chimney Rustic Ales in Hammonton, New Jersey. They will read from their books, answer audience questions and have books for sale.