“Monica,” opening May 19 at the PFS Bourse, is an immersive study of the trans title character (trans actress Trace Lysette), who has returned home to care for her dying mother, Eugenia (Patricia Clarkson), who abandoned her years ago. Director/cowriter Andrea Pallaoro frequently shoots Monica in extreme closeup — capturing a troubled look as she processes a recent phone call while giving a massage to a client — or when she leaves a voice message for a guy she was seeing. Lysette’s interior performance rewards such scrutiny; she makes Monica’s emotions clear in every unflinching frame. A long, unbroken take of Monica driving and then turning around, conveys her conflicted feelings of not being able to deal with her mother and wanting to escape, but also the magnetic pull that she cannot fight.

But “Monica” is a slow film, one that will reward only the most patient viewers. Pallaoro really wants to sit with the characters. Very few scenes feature the camera moving; mostly the characters are seen in the frame, caught in a moment in time. They talk and move around, but in one scene, revealed to be a game of freeze tag, they don’t. Moreover, much of the dialogue consists of characters taking long, pregnant pauses. This may freight the conversations with meaning, but it might also induce sleep.

When Monica appears, Eugenia insists she does not need her help. Monica does not disclose her identity to Eugenia, which suggests a reveal and a showdown may occur before Eugenia passes. But does Eugenia figure it out? She does tell Monica that she wishes she could change her name, suggesting she might know Monica’s identity. Another possibility is that Monica is looking to make peace with her mother who abandoned her. She is there for Eugenia in a time of need, which is more than Eugenia did for Monica. Pallaoro lets viewers decide.

There is almost no discussion about why Monica chose to return home or how long she has been away. The only real information about the fractured relationship is when Monica tells her brother, Paul (Joshua Close) that Eugenia drove her to a bus station and told her, “I can no longer be your mother.” Her remarks are her way of answering Paul’s question, “Was it true that you slept on the streets after leaving home?” Ironically, Eugenia tells her grandson, Brody (Graham Caldwell), that “family comes first” in an earlier scene.

“Monica” wants viewers to be sympathetic to its heroine, and Lysette is ingratiating taking care of Eugenia, and lying with her one night and whispering, in one heartbreaking moment, “There are so many things I want to tell you.” But those things go largely unsaid. Most of the film shows Monica in intense closeup as she grapples with her uncertain feelings.

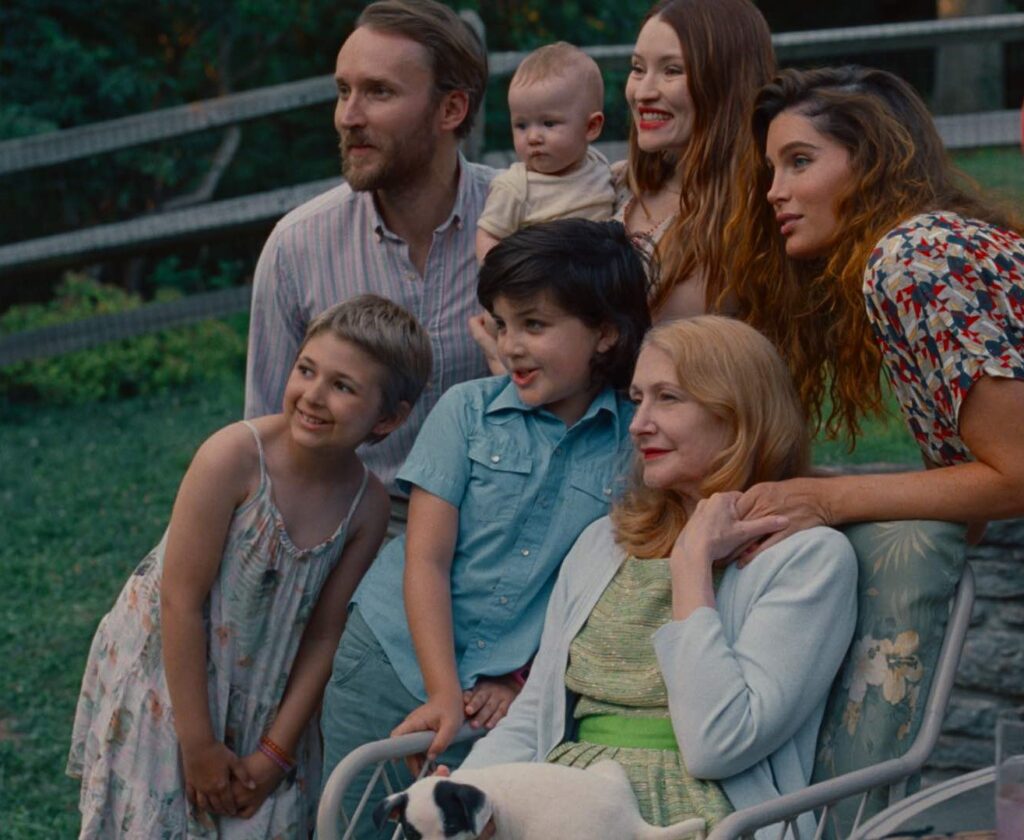

Monica is seen being kind towards Paul and his wife, Laura (Emily Browning), and she is supportive of their children, Brody, Britney (Ruby Fraser), and a newborn, as well as Leticia (Adriana Barraza), Eugenia’s caregiver. As Monica is integrated into their lives, she comes to know and care about them, listening to Leticia talk about her son, or playing with Brody and Britney. A scene of the kids “giving birth” to a doll — they name the “baby” Monica — is interesting as Monica observes and reacts to it. Likewise, when Monica gives Brody a boost of confidence before he sings the national anthem, it is quite moving.

But it is unclear if the children understand who Monica is and how much is known what has transpired in the past. Instead, the film focuses on Monica’s strength and resilience which comes across in various scenes beyond just the difficulties she faces being reunited with her mother who rejected her. Monica is ghosted by a guy who does not show up for a date they made, and she calls her ex-boyfriend a “coward” for the way he dismisses her. Her rage is valid, but the film only provides brief glimpses of her life. Monica is seen working for tips on a webcam in one scene (until her mother calls out for her), and she has sex with a trucker (Bobby Easley) in another.

This approach burdens Lysette to deepen her character. The actress certainly rises to the challenge, emitting a guttural wail when her car breaks down, or telling Paul she is “mostly happy” when he asks. Viewers can decide if she is lying or telling the truth.

“Monica” provides an excellent showcase for Lysette, but the supporting cast seems largely underused. Patricia Clarkson is more fragile than brittle here, speaking in a hesitant, not firm, commanding voice, suggesting how much power she has lost. A scene where Eugenia forgets her words while getting her hair done lacks suitable power, but when she tells Monica, “I never thought I’d be this burden,” is it affecting.

Pallaoro’s deliberately paced drama is frustrating as it teases out aspects of Monica’s life. Thankfully, Trace Lysette’s accomplished performance captivates in a film that largely feels underwritten.