The number of books being banned or facing attempted bans in schools and libraries increased dramatically in 2022, with books that have LGBTQ and/or BIPOC characters predominant among them, as two new reports show. While these trends are not new, the reports find disturbing shifts in the forces behind them.

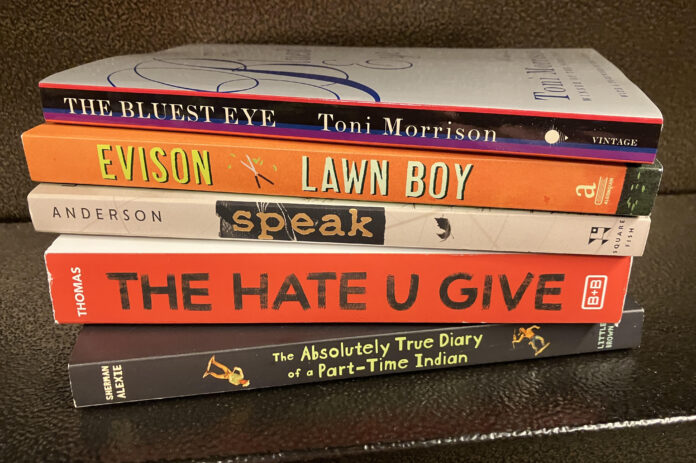

“Gender Queer,” by Maia Kobabe, a memoir about growing up nonbinary and asexual, has topped the American Library Association’s annual list of the Top 10 Most Challenged Books for the second year in a row. Of the 13 books on the list (more than 10 because of ties), seven were targeted because of LGBTQIA+ content.

The list was released April 24 as part of the American Library Association’s (ALA’s) annual “State of America’s Libraries Report,” which found a record 1,269 challenges (demands for censorship) to library, school, and university materials and services in 2022, targeting a record 2,571 unique titles, up from 729 challenges and 1,858 unique titles in 2021, both years charting a significant rise from 2020 and earlier.

Of the challenged titles, the ALA said, “the vast majority” were by or about LGBTQIA+ and/or BIPOC people. That’s unfortunately no different from many past years. The record numbers of challenges now, however, “are evidence of a growing, well-organized, conservative political movement whose goals include removing books addressing race, history, gender identity, sexuality, and reproductive health” from public and school libraries.

The ALA’s findings complement those from a recent PEN America report, “Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools,” which found that between July and December of 2022 there were 1,477 instances of individual books banned in schools (both libraries and classrooms), affecting 874 unique titles from picture books through young adult books, an increase of 28 percent over the prior six months. “Gender Queer” also topped this list.

Over 4,000 bans, affecting 2,253 unique titles, have been recorded since PEN America started tracking them in July 2021, impacting 182 school districts in 37 states and millions of students.

Both the ALA and PEN America note an increase in multiple books being targeted simultaneously. The ALA pointed to “lists of books compiled by organized censorship groups” as the main reason the recent numbers are so high. “90% of the overall number of books challenged were part of attempts to censor multiple titles,” it said. Of those attempts, 40% sought to remove or restrict over 100 titles at once.

PEN America added that while parent-led groups in 2021-22 coordinated many of the book bans, state legislation in 2022-23 is “supercharging” them. School districts “respond to vague legislation by removing large numbers of books prior to any formal review.” Many books are “banned pending investigation” and “removed from student access before due process of any kind is carried out; in many cases, books are removed before they are even read, or before objections to books are checked for basic accuracy.”

The 874 books, across all ages, contained a range of content: themes or instances of violence and physical abuse (44%); health and well-being (38%, including mental health, bullying, suicide, substance abuse, sexual well-being, and puberty); grief and death (30%); race, racism, or characters of color (30%); LGBTQ+ characters or themes (26%); sexual experiences between characters (24%); and teen pregnancy, abortion, or sexual assault (17%). Many books included content in multiple categories. The first three categories are more common than in the previous school year, “largely due to the removal of long lists of books, often covering a wide swath of topics.”

Looking just at banned picture books, however, nearly three-quarters (74%) featured LGBTQ characters and almost half (46%) featured characters of color or discussed race and racism. (Specific percentages were not given for other age ranges.)

Most instances of bans tracked by PEN America were in Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina, “driven by a confluence of local actors and state-level policy.” Yet the influence of these bans goes further, “as policies and practices are modeled and replicated across the country.”

The ALA noted, too, that book bans are only part of the problem. School and public librarians themselves are “subject to defamatory name-calling, online harassment, social media attacks, and doxxing, as well as direct threats to their safety, their employment, and their very liberty,” wrote Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, in the ALA report. In 2022, she added, 12 states introduced legislation “to permit criminal prosecution of librarians and educators for distributing materials falsely claimed to be illegal and inappropriate for minors.” Yet librarians, local residents, library trustees, board members, parents, and other library advocates have in many cases joined together to fight the bans and have had some wins in court, she observed.

All kids need to see themselves, their families, and the world around them reflected in authentic ways. I am heartened by the number of new and upcoming children’s and young adult books that include LGBTQ and other marginalized people. Yes, these books will likely face challenges and bans—but I hope that kids will find ways of obtaining them and that enterprising adults (parents, librarians, and otherwise) will help make them available.

If you encounter book censorship attempts in your community, you can confidentially report them to the ALA (ala.org) and/or the National Coalition Against Censorship (ncac.org). For resources on how to prevent and respond to bans and challenges, visit uniteagainstbookbans.org (an ALA-led coalition that includes LGBTQ organizations, publishers, and others), pen.org/issue/book-bans/, and ncac.org/.