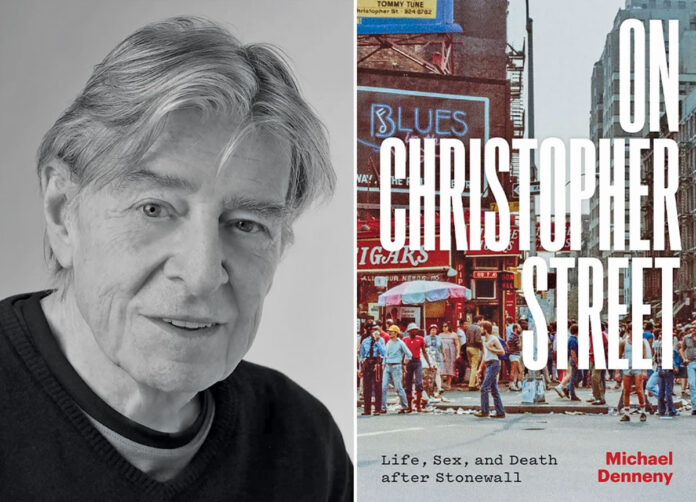

Michael Denneny, who shepherded an entire generation of early LGBT writers during his decades-long career in publishing, passed away last month at the age of 80. His death came one month after his book “On Christopher Street: Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall,” which chronicles his experiences from 1970 to 2014 in publishing and in the LGBT community, was released by University of Chicago Press.

During his career as a book editor, Denneny brought numerous iconic LGBT books to light, including “And The Band Played On,” and he also co-founded Christopher Street, a magazine that published gay writers when few other outlets for gay work existed. He spent the majority of his editing career at St. Martin’s Press, which hired him after he was fired from his position at Macmillan for being openly gay. From that position, he saw the evolution of the industry as more and more LGBT writers began to emerge.

Before his passing, PGN spoke with Denneny about his book, his reason for writing it, and what he thought of the modern day gay rights movement.

First off, why was it important to you to write this book?

Basically, I witnessed heroic moments in the gay community in terms of our response to AIDS. And it was an absolutely shining moment for gay writers, who I think took the lead in alerting the community. There’s no close parallel I know to this in terms of writing. I mean, if you think of the poetry and fiction written about WWI, it was written afterwards. This is almost as if our writers were writing in the trenches mimeographing their work and giving it to be read by other people in the trenches. I think the only parallel might be the tsarist uprising in Russia in the 30s and 40s, Mandelstam, Akhmatova, people like that.

And to my surprise, it seemed to me that works written in the early years of AIDS have been forgotten. Somewhere around 2012, several younger gay academics or reporters did really long interviews with me, and I was really surprised. They knew the facts, but they did not seem to me to have a sense of what it felt like to live through this period. So I wanted to try to do something that would convey what it was like to live through it. That’s why I constructed it the way I did. I took documents from this 30 year period and I did not change them in the slightest. But I did add a sort of voiceover to give the context of the speaking or the writing.

Ed White had an interesting article in the London Review of Books some time ago, where he talked about the new gay fiction. And he analyzed it as “autofiction.” And I have a lot of questions about that, but I also thought that was a great idea, because I could describe my book as “auto nonfiction.” I took these documents, I did not change them, but I tried to contextualize them to give people a sense of what it was like to be there then, which is what seems to me to have gotten lost.

And the other thing was, as I was putting the book together, I slowly realized that basically I think it’s a monument to the first generation of post-Stonewall gay people. It’s a very overused phrase, “The Greatest Generation,” but that’s what they were to me. Mostly the first post-Stonewall generation were people like Mark [Segal], people in their teens and their 20s and early 30s at the time. Which means that they grew up in the 40s and in the 50s. And basically, the 50s were the most intense decade of homophobia in this country. I used to think, as a much younger man, that things always got better over the years. But it turns out historically, that’s not true. It was much better to be a gay man in the 1920s or even in the 1890s than it was in the 1950s. The 1950s really were intensely homophobic, and that’s when this generation grew up. They had internalized the society they’d grown up in, which meant that it took an enormous amount of strength and confidence in themselves, confidence in their experience of life, to fight against that. So to some extent, I think the book ends up being an homage to that whole generation.

You trace the evolution of a lot of gay writers, such as Gore Vidal, who did it kind of carefully and surreptitiously, and then Ed White, who couldn’t sell his novel because it was too gay, and then David Leavitt, who became more mainstream. Do you think the journey of gay men and queer people in publishing followed the same trajectory as the community gaining acceptance in the wider world? Or do you think it was sort of on its own track?

I actually think the publishing industry went first, to some extent. I got convinced in the early 70s, after Stonewall, that you could get that far with zaps. And political processes just seemed not a likely Avenue at all. I mean, we tried to get through nondiscrimination in employment in city council year after year after year, and it was always rejected. In 1976, I was fired from Macmillan. And when I talked to the lawyers from the company, who had become quite friendly, they made it very clear to me that if the CEO said that I was fired for cause, in other words, because I was a lousy editor, they thought I had a very good chance of winning because I had published some very distinguished books and I had made money. But if they had the balls to say I’d been fired because I was gay, and, you know, Macmillan could not have an openly gay man representing the company, that was totally legal.

So basically, I thought that with politics not looking very promising in the early 70s, that what was needed was a change in the imagination, you know, a change in the way we saw the world as gay people. I thought that would have an impact on the larger society. So in a certain way, I don’t think publishing was following the general path to acceptance. I think it was to some extent spearheading the change. And we see some of that today with libraries playing I think an oversized role in gay politics right now with all the bans happening.

There’s an interview with Alan Barnett in the book where you both mention how genre fiction saved the publishing industry and how it kept publishers in business.

Oh yeah. I mean, it saved gay bookstores for sure. The one thing that used to bug me was that I couldn’t do pornography and I couldn’t really do genre romances. Though there were many more of those being produced by the lesbian presses. There were some gay romances that we actually ended up figuring out a way around that. And then I could do big art photography books like Tom Bianchi or Robert Mapplethorpe which were quite moneymakers.

And those books were seen more as art rather than pornographic.

Yeah, there’s actually a funny story about that. Robert had tried to publish the “The Black Book.” And the major publishers in New York City would not touch it. So finally, he came to me. And he gave me I don’t know, maybe 40 photographs, eight by elevens. And I brought it up at the editorial meeting, which took place around a large, round table on the 17th floor. I passed around the photographs, and I realized, as I could see the impact they were having on the editors sitting around it, that I’d made a mistake. I’d moved too early. I mean, they were all these photographs of beautiful black men with fairly large dicks. And it really shook them, I think. And I said, you know, I’ve got to really work with Robert to reselect the photographs and I sort of gathered them back and said, “Now, you know, we’ll work on the presentation. And I’ll bring it back.”

And then I went down to Robert, he had an office about a block and a half away on 23rd Street. And I said, “Do you really want this book published?” And he said yeah. And I said, “then you gotta give me silver gelatin prints.” These were 36 by 42 inches and they were selling for $2,200 apiece. And he said, “Michael, those are very expensive.” I said, “I know. But I’ve got to convince them that this is art.” If I showed them 8 by 11 photographs, what they’re seeing is black men with big dicks. They’re seeing pornography. If I show them these huge silver prints and warn them to be very careful, because they sell for $2,200, they’re much more likely to see art. So that’s what we did. It made me nervous, because I said, I want exactly the same photographs that I had the first time. So I had like, 40 photographs, $88,000 worth of bloody photographs. And I passed them around. And I I lied, I said, “You know, Robert and I have been working on the selection of the photographs, etc. And this is our new presentation.” When in fact, they were exactly the same photographs that everybody had seen a couple of weeks earlier. But this time, they were all okay, because this time they saw art.

I want to circle back to the idea that people were worried that the AIDS crisis was going to completely eradicate that generation of gay writers. You said that that generation of writers really stepped up to the plate and did their job in writing about what was happening. Can you talk a little bit about the importance of gay writers who wrote about AIDS?

I thought this was an incredibly unusual occurrence, because if you look at the history of writing, most writers aren’t terrific from a political point of view. An awful lot of them are reactionaries, and some are just Looney Tunes, you know, in terms of politics. This I thought was one of the few occasions where the writers really had stepped up. They were trying in their fiction and their poetry and their nonfiction to describe actually how we were living now. And therefore, you know, they’re alerting the whole community. And virtually every writer I knew went through a period where they stopped writing. John Preston stopped writing for a year, and then he came back with an anthology of other writers writing about AIDS. But with almost every writer, I know, they had turned to this.

I think Andrew Holleran says at one point, it seemed like the only serious thing to talk about. This disease was killing their friends, their lovers, and endangering themselves. And, you know, the other thing that I don’t think is emphasized enough, this went on from 1983 to 1996, that was 13 years. WWII for America only took three years. This was 13 years in which, until 1996, there was virtually no hope. You had a whole generation that fully expected to die in the next few years, you know, and they wrote books about what that life was like. And they were writing those books for readers who fully expected to die in the next few years.

As I said before, I can’t find any parallel to that in literary history, the closest I could think of is the underground Russian literature under Stalin, which has much fewer people, many fewer people than that were involved in AIDS. So I thought it was remarkable, just for the history of writing and for anybody that’s interested in writing, I thought it was a remarkable period that, to my amazement, seemed, again to be forgotten. The civil rights movement has gone through different periods of activism and more quiet periods, but they’ve never forgotten their history or their heroes. They kept that alive. And it seemed to me that that was not happening in the gay community. And that’s actually why I started to try to put together this book.

You write about how 1977 to 1983 was a hugely important period for emerging gay life, but it got squashed by the AIDS crisis. What about 1977 to 1983 was so important to the gay community?

I think there was a feeling, a mood, of incredible freedom and liberation. You had a whole generation after 1969, there was a sudden, and I’m surprised people haven’t attacked me on this, but one of the things I’ve said was, there was this huge explosion of sexual activity. There was a hugely more sucking and fucking going on after Stonewall than before. There was some before, but there was just an explosion. And you had a whole generation that was exploring the erotic, you know, in their concrete lives. Not just a small elite group like Bloomsbury or something like that, but in fact, an entire generation. And there was a feeling at the time that we could actually change the world, you know? We could change the definition of male sexuality, we could change the definition of the family, we could make things anew. And then, of course, we got slammed with AIDS, and that preoccupied everybody. And I think that period has been forgotten. In the book, I quote Calvin Klein, who said in a newspaper interview at one point that there was Berlin in the 20s, and there was Paris in the 30s, and there was New York City in the 70s. It was a time of immense cultural ferment, that I thought was being forgotten and lost. I mean, yes, it ended up in disaster. And I’ll tell you, I’m sure glad I lived through it.

Felice Picano once told you that early gay writers had an added burden of having to describe gay life because no one had ever done it before. And I wonder if you think current gay writers don’t have that burden anymore.

Oh no, they do have it, because I think gay life has changed so radically since then. One of the things that has become clearer and clearer to me is that this era, from 1969 to the mid 2000s, was an era of gay liberation that has come to a close. We’re in a second chapter of gay history now.

There is a chapter in the book about a talk you did in Louisiana in the 1980s. And during that talk, you mention that back then you could be put in jail or denied housing or fired because you’re gay. And that’s still true in a lot of states today. And I wonder if that surprises you, that there are states still dealing with that 40 years later?

No, what actually surprises me is the states where you don’t have to deal with that. I was just astonished when Pete Buttigieg ran for president. And basically, the fact that he was gay and married to a man, and now has two children, just didn’t seem important to people. People noted it, but it was not a major thing. The last three decades of the 20th century was the first chapter, you know, from Stonewall to the triple therapies to gay marriage and gays in the military; that was the first chapter. But we’ve entered this whole new world now.

In the early days of your career, there was a book released on paragraph 175 and the Nazi war on homosexuals, but you thought people wouldn’t read it. So you wrote a condensed version of the book and its message, hoping that people would at least read that. If you want readers to take away a condensed version of the lessons of your book, what would those lessons be?

That’s a great question. I guess it would be that this particular generation, this first generation of gay liberation, in my opinion, was a really remarkable generation. And it was, though I hesitated to say it in the book because it’s been used to death, the greatest generation. But in fact, that’s how it seemed to me as I was putting together the book. I realized, basically, that what I’m trying to construct here is a collage, a tribute to this generation, a tribute to these people who I thought were quite extraordinary and caused great historical change.