“Little Richard: I Am Everything,” in theaters and on VOD April 21, is a glorious documentary about the legendary Black queer singer, musician, and songwriter who insists, “I am the innovator. I am the originator. I am the emancipator… I am the architect of rock and roll” — and he is not humble bragging.

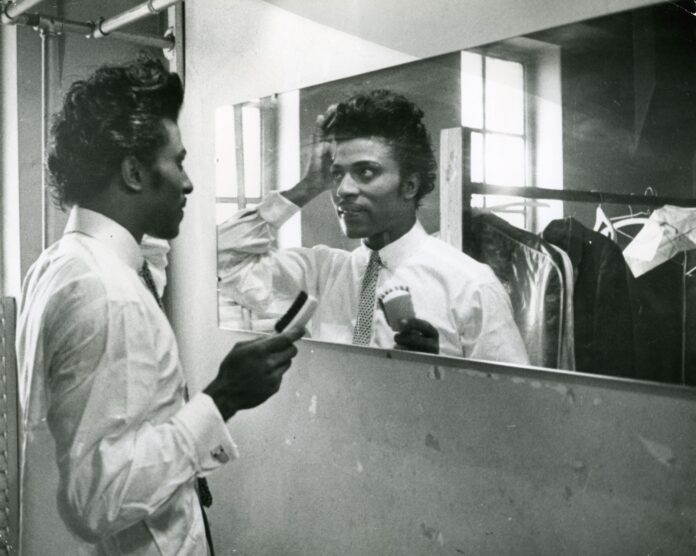

As seen in fantastic archival clips and interview footage, Little Richard is his own best advocate as when he asserts, “I’m not conceited — I’m convinced.” Director Lisa Cortés’ exuberant film shows the pioneering Little Richard influenced everyone from James Brown, Otis Redding, and Jimi Hendrix, as well as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, and more.

Cortés traces the performer, born Richard Wayne Penniman, from his childhood in Macon, GA where he grew up poor with ten siblings, a minister father who did not love him — he put Richard out of the house because he was gay — and a mother who did. Little Richard was different, and not just because he was effeminate; there is a brief interview clip where he talks about having one arm and one leg shorter than the other.

Little Richard embraced his queerness and used it; first performing in drag as Princess Lavonne on the touring (chitlin’) circuit during the 1950s, and then after meeting gay singers Billy Wright and Esquerita, who influenced his sound as well as his style. (Interviewee John Waters says his own pencil thin mustache is a “twisted tribute” to Little Richard.)

Little Richard also faced difficulties because of his race, including working as a dishwasher in a bus station cafeteria where he could not eat or use the washroom. This apparently only drove him to strive harder. When he persisted with his music, he delivered his breakout success, “Tutti Frutti.” The song, however, was about anal sex (the original lyrics: “Tutti Frutti/good booty/If it don’t fit/don’t force it/You can grease it/make it easy”) which were, of course, unsuitable for airplay. After a rewrite that cleaned it up, the record became a hit, and covered by white musicians from Elvis to Pat Boone, who sold more copies of the single than Little Richard did, much to the singer’s frustration.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” shrewdly examines the forces that helped and harmed the performer, which makes it so enthralling. Scholars in the film discuss how he exaggerated his queerness to attract an audience because he was seen as “less threatening.” He also inspired folks like his friend, the trans activist Sir Lady Java, to live authentically. In addition, Little Richard broke down walls of segregation because white audiences would come to the Black-only night shows.

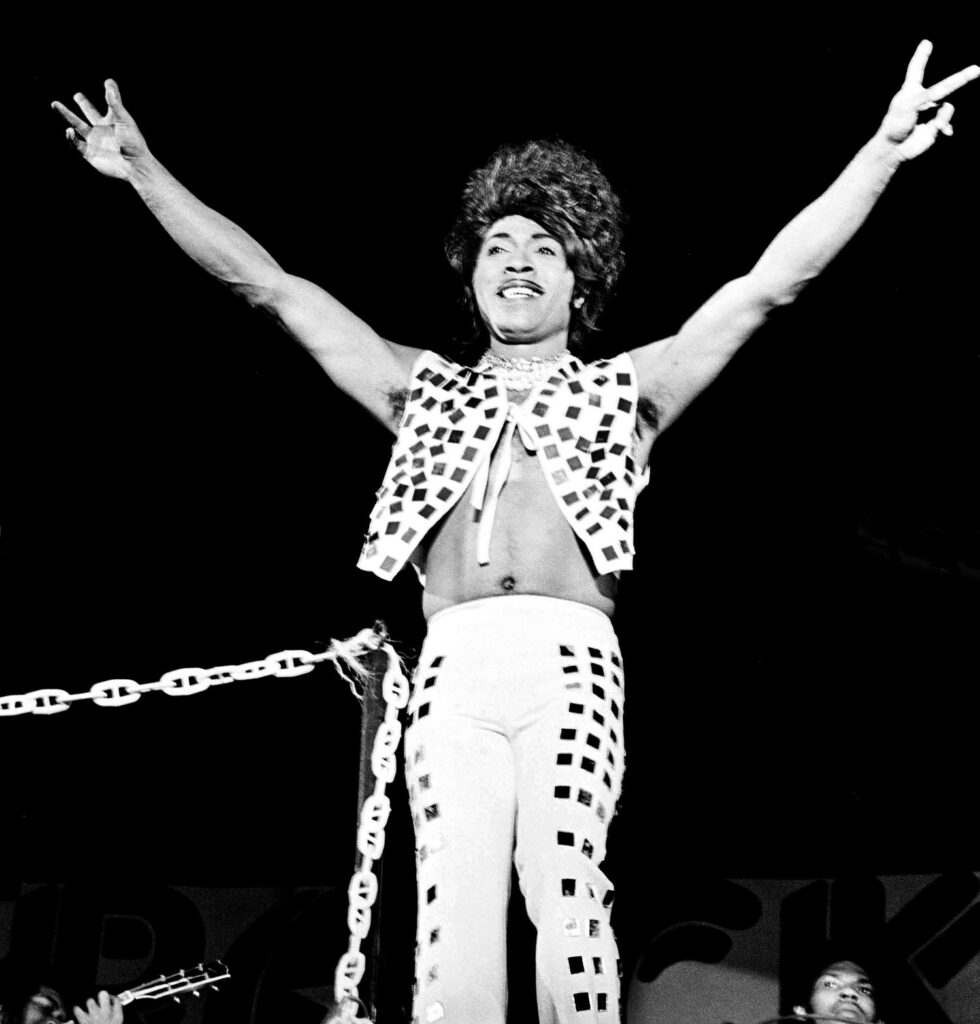

Little Richard’s musicianship was as distinctive as his voice. How can anyone resist his elasticity when he sings “Lucille?” His appearance was equally flamboyant; he favored shirts with mirrors on them. A sequence of him modeling a series of imaginative costumes certainly paved the way for queer performers such as Elton John, Freddie Mercury, David Bowie, and Boy George, among others, and the film makes those clear connections.

Cortés provides plenty of fabulous archival footage of Little Richard on stage and off and his talent and candor is as infectious as it is undeniable. Her film may be a testament to the fact that the world did not quite know what to do with — or make of — Little Richard throughout his career. Her film reminds everyone, as Little Richard does, with a sensational clip of him inducting Otis Redding into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Little Richard also justly bemoans he was never even nominated for a competitive Grammy while he was a presenter at the Grammys.

For all his success in the music industry, however, Little Richard stopped performing after having a spiritual awakening while on tour. He broke off his career (losing royalties in the process) went to Oakwood College, renounced his homosexuality (much to the chagrin of the gay community), and focused on God. He studied religion, sold bibles (but couldn’t earn enough money), and preached. He even made gospel albums in a musical style far more restrained than his other recordings.

The contradictions Little Richard experienced are fascinating. Moreover, they add an element of sadness to his life. The film suggests that everything he did, from his music to his preaching, was an effort to be loved — because he was denied that, by his father and others, because of his race and his sexuality.

When Little Richard was lured back into performing, he toured the UK, connecting with the Beatles and the Stones among others, and he again experienced tremendous success. But he also got involved with drugs. When another tragedy made him hit rock bottom, he went back on God’s path.

Cortés unpacks Little Richard’s strange and wondrous life and career thoughtfully, doing her subject plenty of justice. “Let it all hang out!” Little Richard urges, and this terrific documentary does just that, providing an admirable, appropriate, and affectionate showcase for its subject’s complex legacy.