Lesbians have been working toward social justice in America for centuries, yet despite this long history of activism and groundbreaking work, little history exists about these women. Some lesbians were writers and artists whose work was often the first of its kind, providing activist models and forging new paths for others to follow. The work and writing of these women has too often been hidden from history.

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958) was a member of the renowned abolitionist Grimké family. The granddaughter of a white slave owner and a Black enslaved woman, Grimké wrote essays, short stories and poems often published in “The Crisis,” the NAACP newspaper edited by W. E. B. Du Bois. A member of the Harlem Renaissance, Grimké was also the first woman of color to have a play, entitled “Rachel,” produced in the U.S. “Rachel” was one of the first plays to protest lynching and racial violence. Grimke’s poetry was included in anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance: Alain Locke’s “The New Negro” and Countee Cullen’s “Caroling Dusk.”

Grimké was a life-long lesbian who first expressed her love to other women at the age of 16. At that time she wrote to her close friend, Mary P. Burrill, 15: “I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope, darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife! How my brain whirls, how my pulse leaps with joy and madness when I think of these two words, ‘my wife’.”

According to the African American Registry, “Recent scholarship has revealed Grimke’s unpublished lesbian poems and letters; she did not feel free to live openly as a gay woman during her lifetime.” The “Dictionary of Literary Biography: African-American Writers Before the Harlem Renaissance” states: “In several poems and in her diaries Grimké expressed the frustration that her lesbianism created; thwarted longing is a theme in several poems. Some of her unpublished poems are more explicitly lesbian, implying that she lived a life of suppression, both personal and creative.

Mary P. Burill, (August 1881 – March 13, 1946), Grimke’s first love, became a well-known Black playwright and writer. Burrill was an activist writer and hosted literary salons in her home, which was known as “the Half-Way House.” Burill’s salons provided a venue for intellectual discourse among many prominent writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Burill’s best-known plays are “The Other Wise Man” (1905), “They That Sit in Darkness” (1919), and “Aftermath” (1919). She was an outspoken critic of lynching and the terror it created. Burill also advocated for birth control, publishing plays in radical journals of the time including Margaret Sanger’s “Birth Control Review” and the socialist journal “The Liberator.” After her relationship with Grimké ended, Burill lived with Lucy Diggs Slowe (July 4, 1885 – October 21, 1937) for 25 years, and their home, The Slowe-Burrill House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2020. Slowe was appointed in 1922 as Dean of Women at Howard University, a historically black college; she was the first black dean of women there or at any American university.

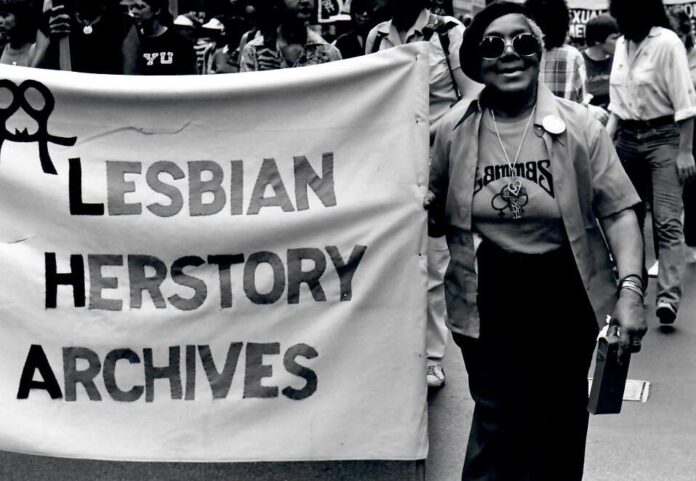

Mabel Hampton (May 2, 1902 – October 26, 1989) was an early lesbian activist, a dancer during the Harlem Renaissance and a volunteer for both Black and lesbian/gay organizations like the NAACP and SAGE. Throughout her adult life, Hampton cleaned houses for white families in New York City, which is how she met Joan Nestle, co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA).

Hampton’s careful and extensive collection of memorabilia, letters and other records are considered crucial ephemera documenting the lives of Black lesbians during the Harlem Renaissance. Hampton donated that collection to the LHA, along with her considerable lesbian pulp fiction collection.

Hampton lived with her partner, Lillian Foster, for over 40 years until Foster’s death in 1978. Hampton spoke at the New York City Pride march in 1984, saying, “I, Mabel Hampton, have been a lesbian all my life, for eighty-two years, and I am proud of myself and my people. I would like all my people to be free in this country and all over the world, my gay people and my Black people.” Hampton was also named the grand marshal for the New York City Gay Pride March in 1985.

Nestle recorded Hampton’s oral histories in the 1970s for LHA. She delivered “I Lift My Eyes to the Hill: the Life of Mabel Hampton as Told by a White Woman,” the first Kessler Lecture for the CUNY Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS), in 1992.

Judy Grahn (born July 28, 1940), poet, essayist and lesbian feminist activist, has said it was her “lived experience of disenfranchisement as a butch lesbian” that led her to writing poetry. Grahn says she grew up in “an economically poor and spiritually depressed late 1950s New Mexico desert town near the hellish border of West Texas.”

In 1969, Grahn co-founded the Women’s Press Collective of the San Francisco Bay area and was a founding member of the West Coast New Lesbian Feminist Movement. Her first poetry collection, “Edward the Dyke and Other Poems” was released in 1971, and her work, “A Woman is Talking to Death,” remains a classic of lesbian poetry. In the latter, she wrote the much-quoted and iconic line, “the common woman is as common as the best of bread and will rise.”

The author of over 20 books, Grahn’s most recent release is the 2021 book “Eruptions of Inanna: Justice, Gender, and Erotic Power.” Grahn earned her doctorate from the California Institute of Integral Studies. Until 2007, Grahn was the director of the Women’s Spirituality (MA) and Creative Inquiry (MFA) programs at the New College of California. She has won several literary awards, including the American Book Award and the Lambda Literary Award. Grahn says, “Gay people are not in the habit of thinking of ourselves as leading our civilization, and yet we do.”

In a 2009 essay for the Boston Review on the poetry of the women’s movement, poet Honor Moore spoke of hearing Grahn read her epic poem “A Woman is Talking to Death” in the early 1970s: “With this poem, the whole political enterprise of feminism was subsumed by poetic means into an understanding of the complexity of the stark power relations that involve gender, race, and sexuality.”

Chrystos (born November 7, 1946, as Christina Smith) is a Menominee writer and two-spirit activist whose books and poems explore Indigenous American civil rights, social justice, and feminism, Chrystos is also a lecturer, writing teacher and fine artist. They write about how colonialism, genocide, class and gender affect the lives of women, notably lesbians, and Indigenous peoples. The author of several books, Chrystos’ awards and honors include a National Endowment for the Arts grant, the Human Rights Freedom of Expression Award, the Sappho Award of Distinction from the Astrea Lesbian Foundation for Justice, a Barbara Deming Grant, and the Audre Lorde International Poetry Competition.

Chrystos’s work has been featured in the anthologies “This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color” (1981), edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, and “Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology” (1988), edited by Will Roscoe. With Tristan Taormino, she co edited the anthology “Best Lesbian Erotica 1999”.

In a 2010 interview for the Black Coffee Poet blog, Chrystos stated, “Since my 20’s, when I saw the need to address social justice issues in words, my work just ‘pops out.’ A newspaper story, an incident from my life, a book, a song, a garden snake, a sad face I see — I have no idea, actually, how these become poems. A line begins in my mind and won’t leave me alone. I’ve learned to sit and write it down and the rest just flows.”

Chrystos notes that their lesbian identity is “an imperative part” of their work and said, “Being a queer woman has given me independence that is not possible for straight women. I’ve never had a boyfriend I had to appease or tone myself down in order to protect his ego. Being a lesbian is being an outlaw—I get to name my own poisons.”