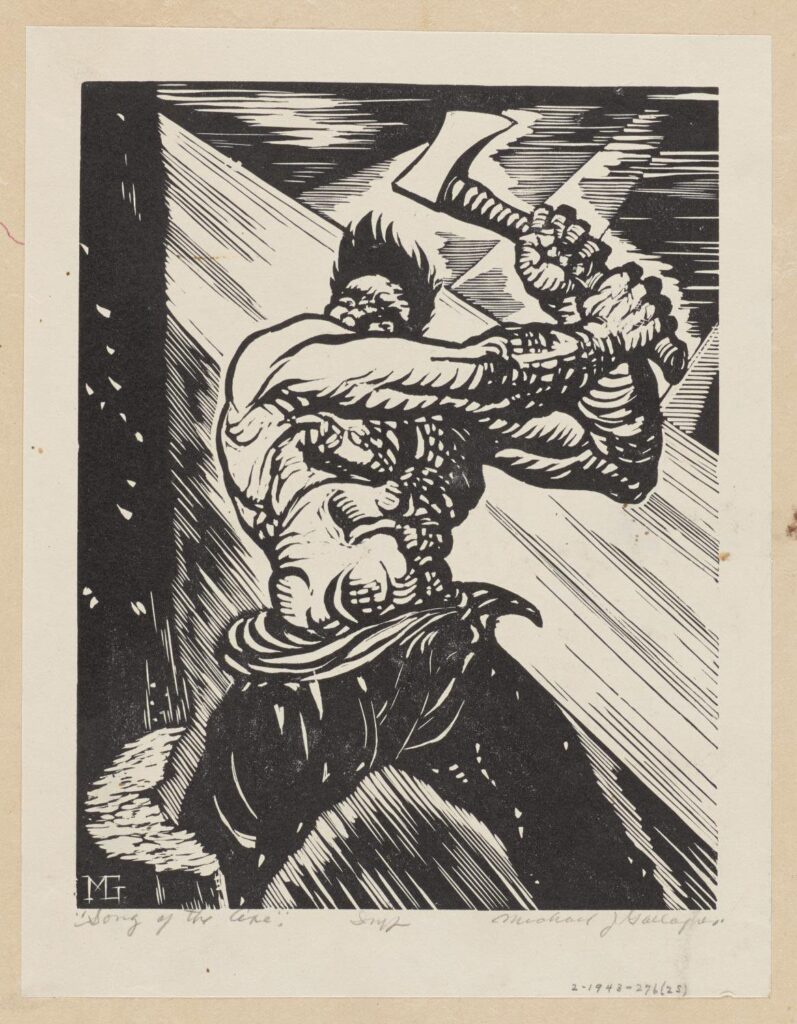

Anyone interested in depictions of male beauty should check out “Macho Men: Hypermasculinity in Dutch and American Prints,” an exhibit on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through March 2023.

“Macho Men” includes more than forty artworks from two seemingly different historical moments: the Dutch Republic circa 1590 and the United States during the Great Depression. In both contexts, artists used images of musclebound men, many partially clad or nude, to explore themes of masculinity, strength, and nationhood.

“Macho Men” was curated by Jun Nakamura, PhD, who is currently the Suzanne Andrée Curatorial Fellow at the PMA. PGN interviewed Dr. Nakamura via email to learn more about this exhibit.

How did “Macho Men” come about? Does it reflect your personal interests as an art historian and a curator?

I specialize in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Dutch prints, and I’ve long been fascinated by this circle of Dutch artists that made these — to my eye — very homoerotic images, which is hardly ever discussed in the scholarship. So I wanted to find a way to invite queer readings of the Dutch prints by putting them with similar works by American artists that have more often been interpreted in these ways.

“Macho Men” presents work from two very different time periods side-by-side. What were you hoping might be revealed by juxtaposing these works?

Placing the works side-by-side also shows how artists in both contexts were not only depicting the same kinds of bodies, but also using the same poses, stacking figures in the same ways, and representing comparable subjects. There were also political resonances: these were countries in national crises (of war and economic depression), and images of impossibly muscled strongmen could broadcast political, financial, and physical health and stability, easing some of those national anxieties.

As you said above, many of these images are homoerotic, and not just in the case of, say, openly gay artist Paul Cadmus’s provocative print “The Fleet’s In!” What do you think is going on here?

The exhibition features male artists showing what they believed an ideal male body was. Regardless of any particular artist’s sexuality, they in effect objectified and sexualized men’s bodies. We can draw connections to comic book superheroes or pro wrestlers nowadays, where big muscled men in spandex tussle with each other as veins bulge from their necks and biceps. What becomes clear from some of the historical context for the American works is that it was actually this kind of overt masculinity that was used to hide queer subtexts or to shield against accusations of homosexuality.

The Cadmus print you mention is a good example: it was censored by the Navy for showing sailors getting drunk and picking up women during shore leave, and it was defended by some who argued the Navy ought to be made up of “he-men” rather than “sissies.” Cadmus’s muscly sailors in tight uniforms were shown as hypermasculine and thus seen as heteronormative, distracting from the fact that Cadmus also included coded references to gay meetups that commonly happened at such ports of call.

So many of these prints depict men in traditionally masculine roles: soldiers, sailors, steelworkers, lumberjacks, and men grappling in sport or combat. Why the emphasis on these specific roles?

I think something that is interesting about the show is that it gets people to think critically about what masculinity is. Like, why are these bodies considered masculine, and how much is the notion of masculinity culturally constructed? What makes a profession masculine? Is violence masculine? Are muscles? And when you see an image of two semi-nude men locked in battle, in a tight physical embrace, where is the line between violence and eroticism?

Hendrick Goltzius’s print “The Great Hercules” is an arresting image — the musculature is so exaggerated and unreal. What can you tell readers about this print?

“The Great Hercules” shows the mythological Hercules muscled to the point of parody. His muscles have muscles. Within decades of its creation the print got humorous nicknames like the “Potato-Man.” But the piles of muscles seem to have also had ideological significance: Hercules has been interpreted as a symbol of the Dutch Republic, which was made up of many smaller provinces and towns banded together as one great political and military “body.”

Do you have a particular favorite from among the American prints of the 1930s?

I really enjoyed going through those because many of them have never been shown at the museum before, and many of the artists are not well known outside specialist circles. One favorite is Hugo Gellert’s illustration for Karl Marx’s “Capital,” where the strength of the working class is represented in hulking nude male bodies. Both Gellert and Goltzius’s images show how male bodies could be symbols of the collective strength of common people.

Is there anything viewers can take from “Macho Men” that applies to the present moment?

During tours, I often talk with visitors about fragile and toxic masculinities, and how these images might have perpetuated or undermined heteronormative understandings of masculinity. In September we did a public program with Collective Strength, a woman and queer-owned strength-training gym in Philly that prioritizes inclusivity, and during that we had some really productive conversations around these topics that felt extremely timely.

Is there anything else about the exhibit that you’d like to mention?

Many of the works in Macho Men turn men into symbols with little agency or subjectivity, so I was happy that in the adjacent gallery leading into the show we were able to exhibit two large self-portraits by contemporary Philly artist James Rose. Rose’s work centers around his experience as a Black man who is large, muscular, and gay, and the relationship between his inner experience and how his physical body is perceived in the world. On February 9th I’ll be doing an online public program in conversation with him, where we’ll talk about Macho Men and how it relates to his own work’s engagement with ideas of sexuality and masculinity.

To learn more about “Macho Men,” visit: https://philamuseum.org/.