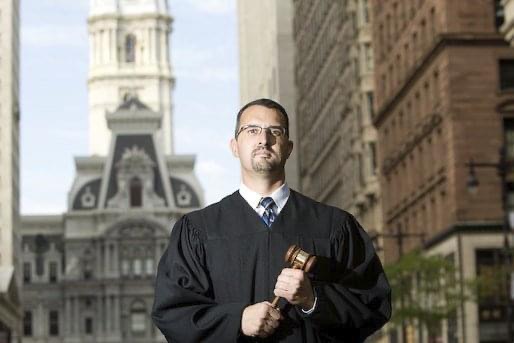

In 2009, when Judge Dan Anders became the first gay man to win elected office in Philadelphia, he had already served as on the bench for two years and worked as an attorney for Pepper Hamilton LLP for nine years prior to that. During his time at Pepper Hamilton, he provided thousands of hours of pro-bono legal services to LGBTQ organizations all across the city and region, which included defending Allentown’s nondiscrimination law and Philadelphia’s domestic partner benefits ordinance.

“It’s really important that we as a society treat everyone equally and fairly,” Anders said during an interview with PGN. “And that’s what I do as a judge. And that’s what I did as a lawyer. I think that the more that people are being out about themselves and openly living as an LGBT person or family, perhaps we’ll have less of a need for those protections.”

Anders grew up in Lancaster and attended Lehigh University, where he majored in political science, and the University of Pittsburgh Law School, where he served as editor of the school’s law review. In Philadelphia, he built a career based on fairness and being able to work with people from all sides, including within the sometimes fractious LGBTQ community. As judge he has served in family court, criminal court and civil court, and in 2020 he was promoted to supervising judge in the civil division, where he oversees approximately 200 court employees, including 30 judges.

Anders spoke with PGN about his road to the bench, his judicial philosophy, and what he enjoys about the law.

When did you know that you wanted to be involved in the legal profession?

I actually started out thinking in high school that I wanted to be a medical doctor, and that was mostly where my focus was. Then I looked at politics, and part of politics is making arguments on behalf of people that you want to see win. And as I got more involved in politics, I saw the opportunity to go into the legal profession. And so it just made a lot of sense to me that in terms of advocating for your client, and advocating for a campaign or candidate, the two overlapped a lot. And so I think the transition was when I went to college, I got more focused on law school, though I didn’t go to law school immediately. I spent five years between college and law school managing political campaigns. And so law school was a bit delayed for me.

Did you find that your work on the campaigns helped prepare you for the realities of the legal profession?

It definitely helped me prepare for the fast pace of doing litigation, and also being nimble on your feet. Political campaigns operate in a very real time manner, and so you never know what a day is going to bring, if some news is going to come out or some some event is going to happen that will change the direction of the campaign. And much like that kind of environment, where it’s really very real time, a litigator does the same thing. They are reacting real time to get new depositions, get new documents and things like that. Certainly trials are like that, too. When people are testifying, sometimes you don’t know what they’re going to say. And that may change the course of the trial.

So it sounds like you might’ve gotten used to adversity.

Certainly used to reacting to not necessarily adversity, but just change, you know, adapting to some new environment when something changed that you didn’t expect.

When you were a lawyer, you did a lot of pro bono work for the LGBTQ community. One of the things you did was you helped defend Allentown’s non discrimination ordinance in 2005, in a case where a landowner refused to rent to members of the LGBTQ community. What was that like for you? What drew you to that that case?

I’m very proud of the fact that when I was in private practice at Pepper Hamilton, that my law firm allowed me to take on as much pro bono work as they did. I forget now if it was 250 or 350 hours a year, but it was a lot of time. And when a big firm like that and allows someone like me to do pro bono work, oftentimes, you can take on higher impact litigation cases, instead of doing perhaps smaller, pro bono representations like doing a will or something smaller like that. And so the then Center for Civil Rights, which is now the Mazzoni Center legal clinic, had asked me if I had an interest in taking on the case, and I did. There were two parts of the case. The first was we were trying to defeat a referendum that would have recalled or invalidated the statute by way of a popular vote. We ended up winning that case by challenging the signatures on the petition and getting it dismissed. The same person then filed a lawsuit challenging the validity of the ordinance. And that was a very significant case because we do not have any, certainly then, any federal protections, and we did not have any state protections. The only protections that existed in Pennsylvania at the time, and still mostly true for now for LGBT anti discrimination protections were from local governments like Philadelphia and New Hope and other smaller municipalities. And so if we lost this case in Allentown, it had the potential effect of taking down or invalidating most of the other protections across the state. Fortunately, we won. And so those protections are secure.

You were appointed judge by Governor Rendell in 2007 and unanimously confirmed by the State Senate. Was it a huge culture shock for you to switch from being a lawyer to being on the other side of the courtroom?

I think for any lawyer, whether they were nine years out of law school like I was at the time or 30 years out of law school like some more experienced judges, it’s a very significant transition to go from being a lawyer to a judge. The responsibilities that you have in the courtroom are different. So although the environment is the same — you’re in the same courtroom and that may seem familiar to you — the responsibilities you have as a judge are much weightier and I think more significant than that of a lawyer. As a lawyer, you have a duty of candor to the court and your ethical obligations to represent your client and your clients interest. As a judge, you have certainly the same ethical obligations, but you can’t favor anyone. And so when I was in a criminal trial [as a judge], I didn’t have any interest in whether the defendant was guilty or not guilty. My interest was to make sure the process was fair, that the evidence that should come in would come in, and the evidence that should stay out would stay out, and then let the factfinder, usually the jury, determine whether the Commonwealth met their burden or not. It wasn’t up to me to impact that decision, other than just making sure that the defendant got a fair trial.

When you became a judge, you started in family court, which I imagine can be a bit harrowing, hearing some of those stories about families and the struggles they go through. How do you keep the compassion for the people in front of you while still remaining fair and objective?

I think that’s an important question, and the best way I can answer it is that my father was a family therapist and did individual therapy and marriage counseling. And so he had in that capacity to hear a lot of family disputes and other issues that people may be dealing with. And he always told me that his clients problems were not his problems. And you have to listen with a little bit of a disengagement. And if you do that, then you’re able to help the person that’s in front of you. And whereas if you get involved and took on those problems as your own problems, perhaps you’re not giving as unbiased advice as you would otherwise be able to provide. And so I took those lessons and applied them to the courtroom, and although I’ve dealt with a lot of abused and neglected kids, and there’s no doubt that everyone has compassion for those persons, you have to make decisions without any particular investment in one party or the other, the mother or the father of a child. And so it’s a good listening skill, to be able to listen and make a decision as that’s the right decision for that family.

One of the things you said you wanted to accomplish as supervising judge was to resume in person jury trials, which had been on hold because of the pandemic. And I know there was a lot that went into that. Tell us a little bit about how you were able to do that and get that to happen so quickly.

We had a one year pause on jury trials from March 2020 to March 2021. And without jury trials, disposition of civil cases tend to come to a complete halt. Parties don’t want to settle and of course if they can’t take something to trial they won’t get a verdict. Preparing to restart the jury trials was a very intensive process that required me to not only partner with the Bar Association and the plaintiff and defense bar and get their ideas, but also learn the science of how does the COVID virus transmit and how do people get infected by being in a courtroom for six or eight hours during the day. So I had to learn about plume transmission versus room transmission and come up with protocols to make sure that we could safely conduct trials. Some of those protocols included everyone wearing a mask, 6-feet social distancing, extensive, disinfecting and cleaning, and plexiglas barriers. We also increased the ventilation by opening windows and using better filters. I had to learn a lot of the science of industrial engineers that look at how airflow moves through a room, and how that affects the likelihood of transmission of the virus within a room. And I can tell you that we’ve done almost probably over 300 jury trials since we restarted and we’ve had no COVID transmissions as a result of doing jury trials. So we’ve been able to do them safely.

It sounds kind of like when you’re when you’re hearing a new case, you have to learn about everyone involved and everything involved. And so this is almost like you had to learn about something new to be able to get this to happen.

That’s certainly true. And I think that’s what I liked about the law generally. If you have a client that makes plastic forks, you’re gonna have to understand everything that they know about the plastic fork manufacturing process to represent them as they should be represented. And then your next client might be a newspaper publisher, then you have to understand all the things that go into publishing a newspaper. And so it’s always a very dynamic and changing environment. I can go from doing a medical malpractice case to a motor vehicle case to a zoning appeal within the space of a year or two. And all of those areas are different and specialized. But it keeps it interesting and that’s just within the civil world. We’ve already talked about I started off in family court, went to criminal for six years and now I’m in civil, and so one of the best things that I can say about being a judge is that you’re not specializing in any one area but you have exposure to a lot of different areas.

As a judge, you also served as the president of the International Association of LGBTQ Judges. I don’t think people even know that that is an organization. So tell us a little bit about that and the work that you did with them.

The International Association of LGBT judges Group was founded in 1993 by a small group of judges, mostly from the US who came together in DC for one of the marches on Washington. And since that day, we have grown to over 600 identified LGBT judges across the world. Most of our members are in the United States, although we have over 50 judges who are members from Canada. We have judges or justices on the highest courts in some countries. For example, we have judges on the High Court for Australia, for the Constitutional Court in Germany, the Supreme Court of South Africa, we have the number two judge in all of England and Wales called the master of the rolls, which is a position occupied continuously since the 1500s. And in the United States, we have probably 20 justices of the highest courts of individual states from New York, California, Washington state, Oregon. Not Pennsylvania yet. Maybe at some point, not me, but somebody will run for that and will be out and qualified to be a state supreme court justice. So where we are in the judiciary, we’re at every level in every type of court.

I think that speaks to what we all know, that LGBTQ people are in every industry and at every level. Let’s switch gears a little bit. We all have our professional worlds and we have our personal worlds. How did you meet your partner, Anh?

I don’t remember when we actually first met but I know that we had known each other from various events and organizations in the community. I think the first distinct memory I had is when we were both in Chicago for the Gay Games in 2006. I went as the mayor’s LGBT chair of his commission, and Anh was competing I think in soccer. And so, I have a distinct memory of meeting him there. And we started dating in May of 2008. So this coming May will be 15 years that we’ve been together.

How do you two like to spend your evenings?

We usually have dinner together and talk about things going on the community or things going on our family or maybe a trip that is coming up. And we usually watch some sort of TV, I tend to have a preference for some sort of reality TV program, not necessarily “Survivor” but more than the line of “Antiques Roadshow” than “Love is Blind.” That’s more Anh’s weaknesses, watching some show like “Love is Blind,” but we tend to meet in the middle.

Anh, too, is greatly involved with the community. And I’m curious if that’s what drew you both together, wanting to make things better for for the neighborhood around you.

Anh’s had a lot of leadership positions in the community, including serving as treasurer and board member of the William Way Community Center. We definitely value our community institutions and want to support them, and we believe that we’re we’re a better community because we do have so many vibrant, mostly volunteer organizations. Whether it be the Philadelphia Fins, which is a historically LGBT swimming group, to Front Runners which is still moving forward, to any of the other organizations, we just feel like we’re we want to support the community because it supported us back in the day.

Final question, what advice would you give to an LGBTQ person who wants to get into the legal world?

I would say for someone who wants to get involved in the legal world, or more specifically wants to go to law school, that they should shadow someone for at least a day or two, whether that be a lawyer or a judge, and that they should really understand why they want to be a lawyer. And they have to have a good reason for that, not simply just to go to law school to get a degree. There are a lot of unhappy lawyers, unfortunately. It’s a profession, not a job. And so you can do an awful lot of good as a lawyer and as a judge. People could certainly reach out to me. I’ve probably dissuaded more people from going to law school than I’ve talked into going to law school.