By Brody Levesque, Washington Blade, Courtesy of the National LGBTQ Media Association

Nov. 11 is Veteran’s Day in the U.S. For much of the rest of the world and especially in Europe, it is Armistice Day, the day that marks the end of World War I, which was also referred to as ‘the Great War.’ On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918 when the armistice was signed, over 20 million people had lost their lives.

“On the 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th month, we will remember them,” General of the Armies of the United States John Joseph ‘Black Jack,’ Pershing. (Sept. 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948)

There are an estimated 1 million currently living lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer veterans in the United States. They have served in the U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines, Coast Guard and now the U.S. Space Force.

They served their country in conflicts spanning from World War II up through “Operation Enduring Freedom” as well as in peacetime. But for many who served until the end of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” on Sept. 20, 2011, and later President Joe Biden’s order ending the ban on transgender service in 2021, they served in silence risking discharge and societal ostracization if their sexual orientation or gender identity was revealed.

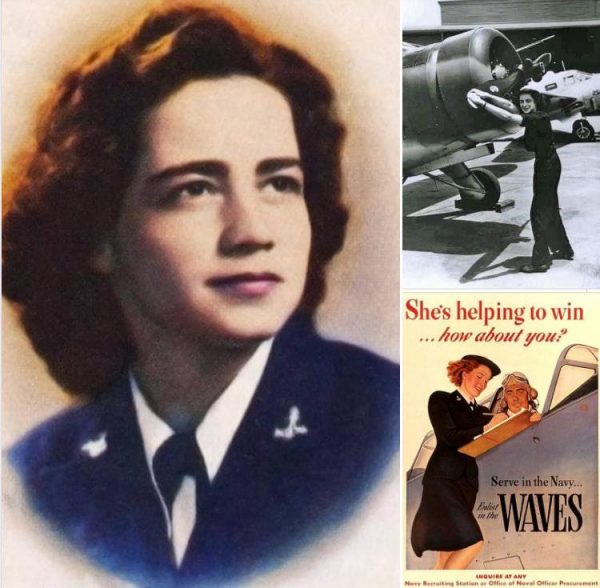

Formerly San Francisco-based LGBTQ activist Michael Bedwell tells the story of Sarah Davis, who served during World War II in the U.S. Navy as a member of the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service.) Davis, whose nickname was “Sammi,” was from a small town in Iowa in the heartland of America.

Davis later said that she joined in 1943 for “the adventure, the excitement. I was going to save the world for democracy. I liked the military life. I liked the discipline. I liked the order. I liked the marching, and the tunes.” Though WAVES could not serve aboard combat ships or aircraft, they supported them; Davis was an Aviation Machinist Mate First Class at the Naval Air Station in Vero Beach, Fla., and she wrote news stories for the Naval Flight Exhibition Team in Jacksonville, Fla.

Before volunteering, she remembered she hadn’t heard “anything about being queer. Didn’t even know that word existed when I went into the Navy. We used to go to the bars open to lesbians, and hug and kiss and so on, but we had to keep things under control. And we definitely couldn’t acknowledge commanding officers who might be lesbian, because you could get into big trouble. You had to form relationships very discreetly and privately.”

After the war, she was interrogated during a witch hunt, a part of the about-face the military did after mostly “looking the other way” during the war once they no longer needed so many troops, and began lecturing new women recruits about the horrors of aggressive lesbians. Davis survived by breaking up with her lover, and denying she knew other gay women, and was ultimately given an honorable discharge. But she told documentary filmmaker Arthur Dong that, “[I]t made me very, very guarded for years and years. It took away what power that I thought I had. It broke my spirit, really, a lot. And that’s been hard to recover, very hard.”

It took many years, but one of the ways she found healing, and came out publicly, was by winning seven gold medals in the seniors category at 1990’s Gay Games. In the interim, she attended Stanford University and USC and graduated in 1952 in occupational therapy and certified in 1956 in physical therapy. In 196, she received a master’s degree in photography from San Francisco State College. She also served in the Peace Corps in 1971 in Swaziland, worked for San Francisco’s Visiting Nurses Association, and became a deacon in San Francisco’s All Saints’ Episcopal Church. For years she lived with her dog, Rambo, in an 1896 three-story Victorian on Clayton Street in the Haight that she bought in 1960, and ran as a boarding house worthy of one of Armistead Maupin’s “Tales of the City” characters.

A 2008 New York Times article about it being remodeled by its new owners upon the move by Davis, then 81, to an assisted living facility noted that, “The mural of a naked goddess that once dominated the entrance parlor is gone, [and] the communal shower with its swinging saloon doors. But a few remnants survive, including a wrought-iron peace sign on the back porch and, in a bathroom, a stained-glass portrait of St. Peter that had been salvaged in the 1960s from a demolished church. Tenants and guests [had] painted walls and ceilings with mandalas, Rastafarian basketball players, and a tree root that morphed into a rabbit, horse and wolf.”

Upon her death the next year back in Iowa, Davis left a trust from her sale of her colorful house benefiting various groups including Marin County’s Canal Alliance that serves low-income immigrant populations with “crisis counseling, a food pantry, classes in English, computers and citizenship, and affordable legal help to keep families together.” A niece wrote: “Aunt Sarah was a positive influence in my life. She always encouraged me to reach for the stars. She lived her life to the fullest, and had many exciting experiences. She followed her mother’s example and continued fighting for women’s rights. She will be missed.”

“Gay and Lesbian soldiers faced extraordinary discrimination during World War II. Most found new communities of people and thrived despite the oppression. Discover the film Coming Out Under Fire that shares their story.” ~ the National World War II Museum, New Orleans.

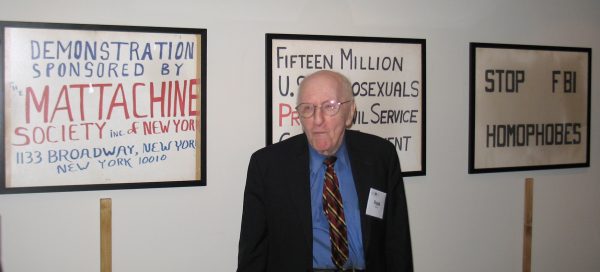

One of the most significant figures in the American LGBTQ rights movement was himself also a veteran. Franklin Edward Kameny had been drafted and served in the Army during World War II and later upon discharge he matriculated first at Queens College, City University of New York, then attending graduate school at Harvard University he earned a doctorate in astronomy.

While working as an astronomer in the Army Map Service in D.C., Kameny was outed and fired from his position in 1957 leading to his 54 years long career as a LGBTQ activist and spokesperson for equality, which only ended when Kameny died on National Coming Out Day on Oct.11, 2011.

Kameny had a lengthy list of accomplishments during his career as an activist including his being a co-founder of the D.C., Mattachine Society, and along side the Mattachine membership launched some of the earliest public protests by gays and lesbians with a picket line at the White House on April 17, 1965.

He also worked to remove the classification of homosexuality as a mental disorder from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

(Photo by DC Virago)

In the early 1970’s Kamney became friends and worked with an Air Force Vietnam veteran who soon became the public face of gays in the military.

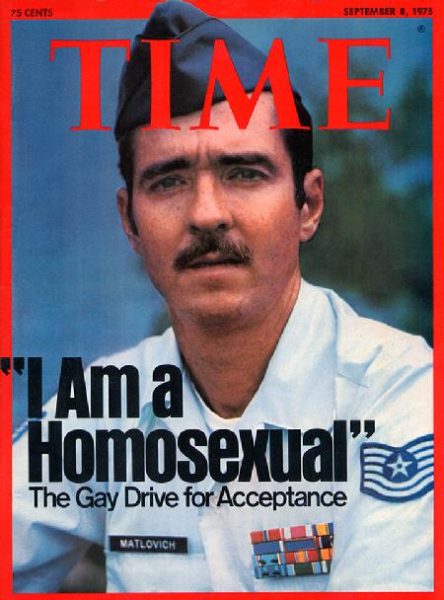

“When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” ~ from the headstone on the grave of Technical Sergeant (TSgt) Leonard Matlovich, U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force Technical Sergeant (TSgt) Leonard Matlovich, U.S. Air Force had served three tours of duty, earning the Bronze Star for bravery, the Purple Heart and an Air Force commendation during his time in Vietnam.

In March 1975 Matlovich became the first uniformed member of the armed forces on active duty to challenge and fight discrimination against gays and lesbians and he became the first openly gay person to be on the cover of “Time Magazine.”

Although he was ultimately discharged in 1980, a federal judge ordered the Air Force to reinstate him with back pay. The Air Force negotiated a settlement with Matlovich and the federal court’s ruling was vacated when he agreed to drop the case in exchange for a tax-free payment of $160,000.

Matlovich, like Frank Kamney became active in gay rights and AIDS organizations.

In 1986, he was diagnosed with AIDS, and when he succumbed to the disease and died in West Hollywood, California in June 1988, his body was returned to D.C. and buried at the Congressional Cemetery in Southeast Washington with full military honors.

The stories of LGBTQ veterans span beyond activism. In August 2021 during the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan, a trans government contractor for the State Department and former U.S. Air Force Sgt. Josie Thomas found herself trapped along with her colleagues at the diplomatic support facility known as Camp Alvarado located on the outskirts of Afghan capital city’s airport.

Thomas, in a series of text messages provided to the Washington Blade on background by a colleague of hers, relayed that she and others were aware of the immediate presence of the Taliban insurgents, which was communicated at the time Afghan security forces had abandoned their posts.

One of her colleagues communicating with Thomas received a text from her stating that elements of the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division had arrived at the Camp Alvarado diplomatic support facility:

“Just talked to her again for several minutes. The 82nd has taken control of her compound and there’s a clear route from there to the flight line now. That the place is looking like a refugee camp with the amount of displaced coalition personnel and there’s no aircraft coming in to evacuate people yet.”

On Aug. 17, she was evacuated and flown home.

*

Likely one of the most high profile contemporary LGBTQ military veterans is the current Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, shown in the featured photograph with his parents. Buttigieg, a graduate of Harvard College and the University of Oxford, served in the U.S. Naval Reserve from 2009 to 2017 and left with the rank of Lieutenant (O-3.)

Buttigieg, the first openly gay man to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate to a presidential cabinet post had previously been elected and served as the 32nd mayor of his hometown of South Bend, Ind.

These are but a very select few stories of the tens of thousands of LGBTQ Americans who have proudly worn the uniform of their country.

(Photo credit: U.S. Army Photography Unit, the Pentagon, Military District of Washington)

On Memorial Day 2013, this reporter, while working as the Washington Bureau Chief for another LGBTQ publication encountered the story of one of those veterans:

ARLINGTON, Va. — Every year that I have lived and worked in this city [Washington, D.C.] I have always gone to Arlington National Cemetery to observe the Memorial Day ceremonies.

Afterward, I wander through the grounds, just to watch, maybe to listen, but mostly to contemplate on the sacrifices made by those brave souls whose final resting place has become hallowed ground — a literal garden of stones.

Arlington’s rolling hills are a place of extraordinary beauty, a fitting repository for the memory of the living history of the United States. Names from the history books leap off the pages as one strolls through the grounds: “Byrd, Taft, Lincoln, Kennedy, Rickover, Marshall, Pershing,” followed by the names of the thousands of soldiers, sailors, airmen, and coast guardsman who gave their lives to secure the freedoms promised by the American Constitution.

In his remarks today, President Barack Obama reminded Americans they must honor the sacrifices of their military service members, particularly as U.S. combat roles change and the nation’s involvement in Afghanistan is winding down.

Adding that Arlington “has always been home to men and women who are willing to give their all … to preserve and protect the land that we love,” the President praised the selflessness that “beats in the hearts” of America’s military personnel.

Obama’s words stuck with me as I walked along through the ocean of gravestones, pausing occasionally to read the names, the inscriptions, and wonder what each person was like.

Scattered throughout the graves proudly marked with miniature American flags fluttering in the bright noontime sunlight, I observed families, loved ones, and friends who had come to honor their fallen.

Then I happened upon one grey haired older gentleman standing quietly in front of a headstone, obviously lost in his thoughts. As I tried to unobtrusively move around him, he look up at me and smiled.

I greeted him, and he greeted me back. He saw my press credentials hanging from my neck and asked whom I worked for.

I told him, momentarily wondering what type of reception I’d receive as, let’s face it, the LGBTQ community still has its detractors, and to my shock, he looked back at me, with tears forming in his eyes.

“You’re gay?”

“I am,” I answered.

“Lot of changes since I was a, a kid,” he trailed off. I pointed at headstone and quietly asked if the person was a friend or a family member.

“He’s my, well was my best bud, yeah, I dunno…”

The gentleman looked stricken and it was certainly not my intention to interview him, impromptu or not. But yet I sensed that something was left hanging so I took the plunge and asked him for a few details, if he didn’t mind sharing them. As it turns out, that’s exactly what he wanted… to share, to have a conversation about the person whose grave we were standing over.

The two men had grown up in eastern Ohio, in a small rural farming community. They played football, went fishing, did farm work, and discovered that after a few failed attempts at pursuing the fairer sex, their real romantic interests laid in each other.

By the time they had graduated from high school, the Vietnam conflict had escalated and, rather than wait to be drafted, they decided to join the U.S. Marines together. They went to boot camp, and not long after graduation, found themselves on troop planes headed for Vietnam.

“We were lucky,” he said, “We both got assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 26th regiment.”

But good luck turned sour as their battalion found itself in the middle of one of the nastiest battles of the 1968 Tet Offensive in the battle for Khe Sanh.

“I lost him that morning,” he told me, pointing at the inscribed date of death on the simple white marker — February 7, 1968. “He was just 19.”

The tears came freely and I waited. Then we talked some more.

He told me that after he lost his love, “I went straight and got married.” Just a fews years ago, he lost his wife to cancer.

He has grandkids that he says will never know the truth — he just can’t be open with them, but at the same time, never does a day go by that he doesn’t think about and mourn the loss of his friend, his partner — and the promise of what might have been.

“I was glad to see DADT end,” he told me. “At least some other couples won’t have to hide like we did.”

I thanked him for his service and his time talking with me and walked away reflecting on all of the unknown LGBT military folk buried around me who, like that lost soldier, suffered in silence and hid, yet still believed in a greater good of which they ultimately gave their lives for their country.

*

Across Lafayette Park on Vermont Avenue, N.W., a block from the White House, stands a nondescript government office building that houses the headquarters of the Department of Veterans Affairs. On a pair of metal plaques at its entrance is inscribed the words of the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, which define the motto of the agency: “To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs is a leading provider for healthcare for LGBTQ vets. While the VA is working to be a national leader in health care for LGBTQ veterans and wants to assure that high-quality care is provided in a sensitive, respectful environment at all VA health care sites nationwide, the fact remains that these LGBTQ veterans can face increased health risks and unique challenges in accessing quality health care.

Maj. Tyler McBride, 62nd Fighter Squadron F-35A Lightning II instructor pilot, and Capt. Justin Lennon, 56th Training Squadron F-35 instructor pilot, hold an LGBTQ+ Pride flag after a Pride Month flyby June 26, 2020, at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona. McBride and Lennon performed the flyby over Luke AFB to celebrate and highlight the LGBTQ+ community. (Leala Marquez/U.S. Air Force)

Many LGBTQ veterans may receive care at the Department of Veterans Affairs, but others may be unaware of what services are available or have concerns about discrimination.

What is VA’s policy on LGBTQ veterans?

According to the VA, its policy is — all veterans deserve respect and dignity. VA has a nondiscrimination patient care policy that includes sexual orientation and gender identity and expression. Specifically, it is the policy of Veterans Health Administration “… that staff provide clinically appropriate, comprehensive, veteran-centered care with respect and dignity to enrolled or otherwise eligible transgender and intersex veterans, including but not limited to hormonal therapy, mental health care, preoperative evaluation and medically necessary post-operative and long-term care following gender confirming /affirming surgery. It is VHA policy that veterans must be addressed based upon their self-identified gender identity… ” (VHA Directive 1341, p. 3)

What services does VA provide for LGBTQ veterans?

Each VA facility is required to have an LGBTQ coordinator who can connect veterans with culturally competent providers, educate staff about where gaps in knowledge/training exist and to help create a more welcoming environment. (VHA Directive 1341, May 23, 2018)

The VA is authorized to provide:

- Hormone treatment

- Substance use/alcohol treatment

- Tobacco cessation treatment

- Treatment and information on prevention of sexually transmitted infections/PrEP

- Intimate partner violence reduction and treatment of after effects

- Heart health

- Appropriate cancer screening, prevention and treatment

What can LGBTQ veterans expect when accessing their earned benefits?

It is important for LGBTQ veterans to let providers know about sexual activity and identity so they can appropriately screen them for potential medical issues. Additionally, VA providers may ask about sexual orientation, gender identity, sexual health and social experiences which may involve exposure to violence in the home, or assess for homelessness. This information can help providers guide veterans to resources, services and programs that can address their unique needs.

LGBTQ veterans can be assured their providers will keep any information they reveal confidential. They can ask that their gender identify or sexual orientation not be revealed in their medical record although this may compromise their ability to receive appropriate care.

Where can a veteran learn more?

More information on the VA’s LGBTQ veterans policies and programs can be found here. The VA has also made available the following fact sheets to identify health care topics for sexual and gender minorities:

- VA Health Care for Transgender Men

- VA Health Care for Transgender Women

- VA Health Care for Gay and Bisexual Men

Story courtesy of the Washington Blade via the National LGBTQ Media Association. The National LGBTQ Media Association represents 13 legacy publications in major markets across the country with a collective readership of more than 400K in print and more than 1 million + online. Learn more at https://nationallgbtmediaassociation.com/.