by Eszter Kutas

In most tellings of the Holocaust, the Jewish community takes center stage. And for good reason — Jewish people were the Nazis’ primary target for total extermination. However, during precisely the same time period, other groups of minorities were also incarcerated, terrorized and dehumanized. While this is a conversation that typically finds its way into Holocaust education at select moments throughout the year — notably during Pride Month, when a much clearer collective effort is made to remember the toll inflicted on LGBTQ+ invidiudals by the Nazis — this broader discussion is far more important than is often acknowledged. For this very reason, the leaders and educators who champion Holocaust education must make a stronger, conscious effort to broaden the Holocaust narrative, ensuring that the stories of all victims are honored year-round.

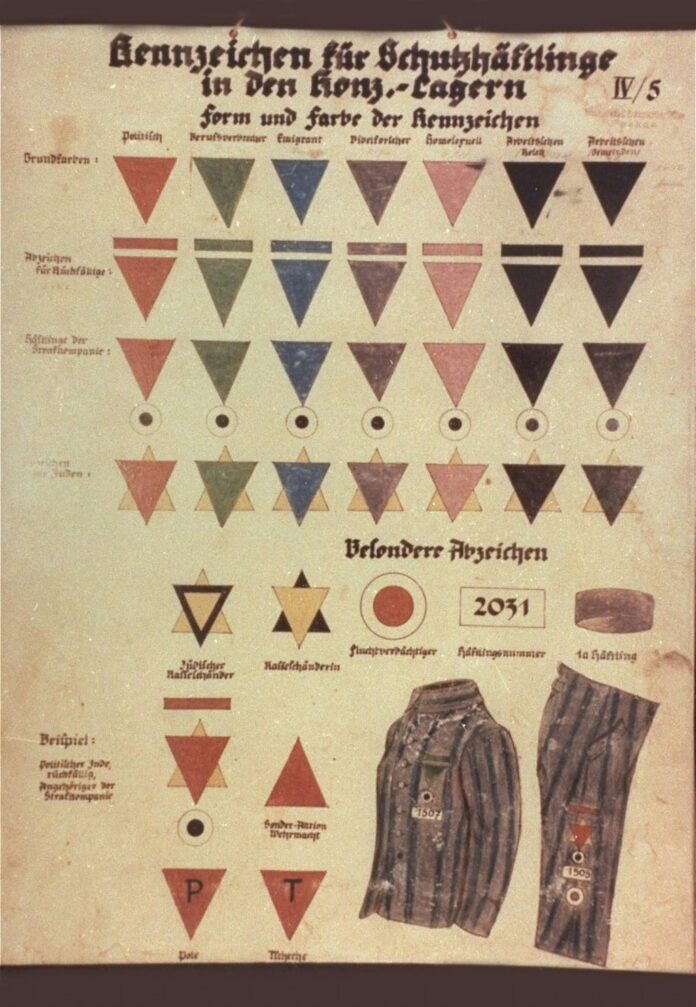

Perhaps nowhere is the lack of familiarity with basic historical events more pronounced than with Nazi “markings.” Studies have shown a lack of knowledge of the Holocaust; however people with even elementary Holocaust education are usually aware of the significance of the yellow Star of David and its use as an identifier of Jews. On the other hand, the markings forced by the Nazis upon so many other minorities — who were persecuted because of their race, ethnicity, political positions, or sexuality — are unrecognizable to most.

LGBTQ+ individuals

For the LGBTQ+ community, this marking was a pink triangle. The basis for imprisonment of these individuals was Article §175 of the German criminal code which stated that “unnatural” sexual activity between men, which was categorized alongside bestiality, would be “punished with imprisonment, with the further punishment of a prompt loss of civil rights.” This text in and of itself, juxtaposing intimacy between gay men with the grotesque act of bestiality, perfectly exemplifies the ideologies that posed a significant, recurring threat to the LGBTQ+ community throughout the war and in the years following it.

In fact, the gay community was oppressed in Germany for decades after the Holocaust. More than 100,000 gay men were arrested by the Nazis, but their persecution persisted in Germany for many years, with LGBTQ+ Holocaust victims having to fulfill prison sentences after the end of the War. These victims were not even included in German death tolls or eligible for reparations until 2002.

Romani people

The Romani people were forced to don a black or brown triangle marking given to prisoners attributed to the “asocial” class. In theory, this signifier was meant to identify prisoners who were held for crimes such as vagrancy and sex work, but this proved to be a loose standard often imposed with racially charged and biased intentions. Members of the Roma community were victims of Nazi violence based on long-held prejudices that deemed these individuals as social pariahs and racially inferior. Similar to Jewish individuals, Romas were thought to threaten the “purity” of the Aryan race. By the time the war finally reached its end, hundreds of thousands of Romani men, women, and children across Europe had been killed at the hands of the Nazis.

Political adversaries

As the Nazis were hostile toward any form of critisism or dissidence, it’s no suprise that their political adversaries were among the first to face persecution. These victims, who were marked in the camps with red triangles, appeared to threaten the advancement of a fascist, radical right-wing ideology that scorned liberal ideas. (To the Nazis, there were few crimes greater than the promotion of individualism versus collectivism.)

Prisoners with these red triangle markings typically represented the Nazi’s belief that, through punishnent, they could re-educate members of the “superior race” who held contesting political views. In this process, they hoped these prisoners would accept the Nazi worldview to avoid a fatal outcome.

The Nazis made victims wear these markings to degrade and dehumanize them. As part of Holocaust remembrance, we should remember the way the markings were used to stratify classes of victims and respect the ways marginalized communities struggled to preserve their individuality and core values. But as we recall the Nazi emphasis on these differences, it’s critical to focus on our shared humanity, which should transcend any external differences.

At the Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation, we take these messages to heart, and have been creating new programming to remember the shared suffering of both the persecuted Jewish and LGBTQ+ communities and collectively work to ensure that persecution is not perpetuated. This year, we’ve held several events focused on the experiences of LGBGTQ+ individuals and the Holocaust, including a Pride Havdalah event in collaboration with J.Proud, Congregation Rodeph Shalom and other partners, which took place a few weeks ago at the Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza on the Parkway. Earlier in the year, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we hosted another event that focused exclusively on LGBTQ+ people during the Holocaust.

In the years ahead, we will continue to play an active role in these remembrance efforts, as it is our obligation to commemorate and honor all victims of the Holocaust, pay homage to their fight and take comfort in the common humanity that brings us together in the face of evil.

Eszter Kutas is an accomplished nonprofit professional and lawyer who became Executive Director of the Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation in 2019 after serving as the project lead and acting director for two years while working at nonprofit consultancy Fairmount Ventures. The granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors, Eszter’s first professional role was at the Claims Conference in New York City, where she helped determine how to distribute a $1.25-billion settlement from Swiss banks to compensate roughly 800,000 Holocaust victims and their descendants for lost assets. After four years at the Claims Conference, Eszter worked for Philabundance, where she served in a variety of project management and fundraising roles and helped launch Fare & Square, a nonprofit grocery store, to address the issue of food deserts.