When Urvashi Vaid died at 63 in May 2022 after a valiant fight with breast cancer, thousands of LGBTQ people who had been touched by her decades of activism mourned her passing. Over a half-century of activism that began when she was only 11, Vaid worked on a breadth of issues, including LGBTQ civil rights, women’s rights, the rights of prisoners, immigration justice, and health care justice.

Vaid’s activist voice was unique and unequivocal. She insisted decades ago that the fight for LGBTQ rights must not be dismissed nor demeaned by the language of straight politicians or the religious right. At the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation in April 1993, she said, “The gay rights movement is not a party. It is not a lifestyle. It is not a hair style. It is not a fad or a fringe or a sickness. It is not about sin or salvation. The gay rights movement is an integral part of the American promise of freedom.”

In a tribute to Vaid in The New Yorker magazine, Masha Gessen wrote that Vaid “was, almost certainly, the most prolific LGBTQ organizer in history.”

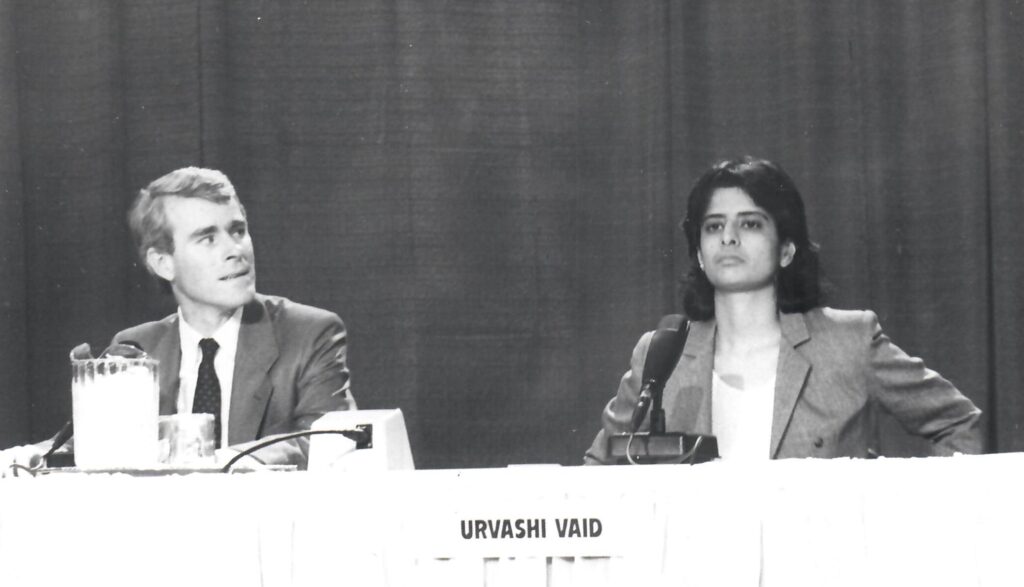

A fair and fitting assertion about the lesbian activist who for a decade led the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (now the National LGBTQ Task Force) through one of the most tumultuous periods in LGBTQ history, the AIDS crisis, first as media director and then as executive director. Vaid’s was a constant presence on the national political stage at a time when overt LGBTQ activism had yet to become mainstreamed. In 1990 Vaid was thrown out of an address being given on the AIDS crisis by President George H. W. Bush when she held up a sign that said: “Talk Is Cheap, AIDS Funding Is Not.”

After Bush died in 2018, Vaid told NPR’s “All Things Considered,” “The fact is that we were doing our best and hardest work in our community to build social services, to fight discrimination,” she said. “People were being rejected at hospitals. People were being turned away from mortuaries. We were dealing with that while dealing with loss. So I think what could have been done was done because of the activism. And more could have been done had the White House not been, frankly, bad on issues affecting LGBT people because they had bias.”

The impact Vaid had in those roles at NGLTF, as a voice continually challenging the anti-LGBT policies and positions of the Reagan/Bush presidencies, cannot be overstated. Thousands of gay men were sick and dying in America and Vaid was the warrior fighting those administrations to save lives.

During ACT UP’s first national action, Seize Control of the FDA, Vaid devised a plan to pair local reporters with protesters from each media market. At the action, protesters were given signs with the cities they came from and ACT UP announced them to reporters. “And that made the difference between the protests getting page five in the Arizona paper, or The Dallas Morning News, and being on the front page, because there was a local person there,” Michelangelo Signorile told the ACT UP Oral History Project.

Toward that activism and other goals, Vaid co-founded the annual Creating Change conference and symposium with Sue Hyde, which Hyde still directs for the Task Force.

“Urvashi Vaid was a leader, a warrior and a force to be reckoned with,” National LGBTQ Task Force’s Executive Director, Kierra Johnson, said in a press release. “She was also a beloved colleague, friend, partner and someone we all looked up to – a brilliant, outspoken and deeply committed activist who wanted full justice and equality for all people.”

Johnson called Vaid, “one of the most influential progressive activists of our time.”

Vaid left NGLTF in 1992 to write her pathbreaking book, “Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation,” which won the Stonewall Book Award in 1996. She returned to the Task Force in 1997 as director of its Policy Institute think-tank.

Virtual Equality, published in 1996, was an integral step in Vaid’s activism and personal philosophy of change. The book explicates Vaid’s signature thesis, that it is liberation, not tolerance from the dominant cis-het culture, queer and trans people must strive for as a community.

The 1990s had seen a strong move towards assimilationist politics and policies within the (then) gay and lesbian movement, which was focused largely on the fights for marriage equality and openly gay military service, issues that addressed only limited areas of LGBTQ life. Vaid argued that while the mainstreaming of lesbian and gay issues was an important aspect of activism, it must not limit or subvert the quest for liberation: the right of all LGBTQ people to feel safe in their own sexual orientation and gender identities rather than being forced, like Black Civil Rights activist Bayard Rustin, to closet themselves in the mainstream arena so as not to challenge the status quo.

Vaid wrote, “By aspiring to join the mainstream, rather than figuring out all the ways we need to change it, we risk losing our gay and lesbian souls in order to gain the world.”

Vaid was always working for social justice. Born in New Delhi, India in 1958, she moved to the U.S. with her parents and two sisters when she was eight and was an anti-war protestor by 11, attending the Moratorium on the Vietnam War.

While earning her undergraduate degree in political science and English literature at Vassar College, Vaid engaged in political and social justice actions, including working to get the college to divest from then-apartheid South Africa. In 1983, as a law student at Northeastern University School of Law in Boston, Vaid founded the Boston Lesbian/Gay Political Alliance, worked off-campus at the weekly newspaper Gay Community News, and pushed to have the university add sexual identity to its nondiscrimination clause.

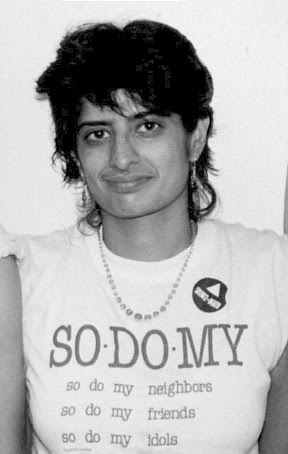

After college, Vaid was a staff attorney at the National Prisons Project of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) for three years before going to NGLTF. At the ACLU, Vaid started the agency’s work on HIV/AIDS in prisons. During that time, she helped organize a demonstration at the Supreme Court following the Bowers v. Hardwick decision, which allowed sodomy laws to stand.

In an interview with Curve magazine in 2013 when she published her book “Irresistible Revolution: Confronting Race, Class and the Assumptions of LGBT Politics,” Vaid spoke candidly about her long years of activism and her concerns that some gains in LGBTQ civil rights would lead to complacency. She said, “One of the worries that underlies my book is a movement that demobilizes because it finally wins marriage equality.”

She also declared at the time that she was on a new mission: to make sure that LGBTQ people broaden the movement and be more inclusive with regard to race, class, and gender.

Vaid told Curve, “What can I say? I write in the book about how many times I have been the only woman of color in the room — or even the only woman.”

She said, “I wanted to make explicit [in the book] the limits of the LGBT movement and the assumptions that we operate the movement under — that everyone is white, everyone is middle class.”

That was what Vaid devoted her life to: inclusion. She founded LPAC, the first lesbian Super PAC, in July 2012. As of the 2020 election, LPAC had invested millions of dollars in candidates committed to legislation promoting social justice.

Vaid also spent a decade working in global philanthropic organizations. As Executive Director of the Arcus Foundation from 2005 to 2010, she focused the grant-making foundation on issues related to sexual orientation, gender identity, and race. She served on the board of the Gill Foundation and Ford Foundation and was the Director of the Engaging Tradition Project at the Center for Gender and Sexuality Law at Columbia Law School from 2011 to 2015. Vaid also helped create the ongoing National LGBTQ women’s community survey.

In addition to founding LPAC, Vaid founded the Vaid Group LLC, which works with social justice innovators, movements, and organizations to address structural inequalities based on sexual orientation, gender identity, race, gender, and economic status.

Vaid’s work did not go unnoticed, She was The Advocate’s Woman of the Year in 1991, one of Time’s 50 key leaders under 40 in 1994, and she appeared on Out magazine’s list of the 50 most influential men and women in America in 2009. Vaid and her partner since 1998, comedian Kate Clinton, often appeared as a glam couple at queer events and awards ceremonies.

As Vaid’s friend, MSNBC anchor Rachel Maddow, told The New York Times after Vaid’s death, “She put the gay rights movement in a progressive context that no one else can lay claim to.”

Maddow said, “She really had a singular impact as an individual. She changed the AIDS movement, gay rights and the civil rights movement in ways directly attributable to her.”

Vaid wrote in Virtual Equality what now stands as a fitting epitaph to her life and work: “We call for the end of bigotry as we know it. The end of racism as we know it. The end of child abuse in the family as we know it. The end of sexism as we know it. The end of homophobia as we know it. We stand for freedom as we have yet to know it. And we will not be denied.”