As part of breakthrough curative research on HIV, a gene-editing therapy for HIV has for the first time been administered to a human living with the virus, thanks to a collaboration between researchers at Temple University’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine and Excision BioTherapeutics.

The researchers are hoping that the intravenous infusion EBT-101 therapy, which is currently in clinical trials, will make it so the patient no longer has to undergo antiretroviral therapy, which is the standard treatment for HIV.

The EBT-101 Phase 1/2 clinical trial began on the heels of research led by Kamel Khalili, Ph.D., Laura H. Carnell professor, chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Inflammation, director of the Center for Neurovirology and Gene Editing and director of the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center; and Tricia H. Burdo, Ph.D., professor and vice chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Inflammation at the Lewis Katz School.

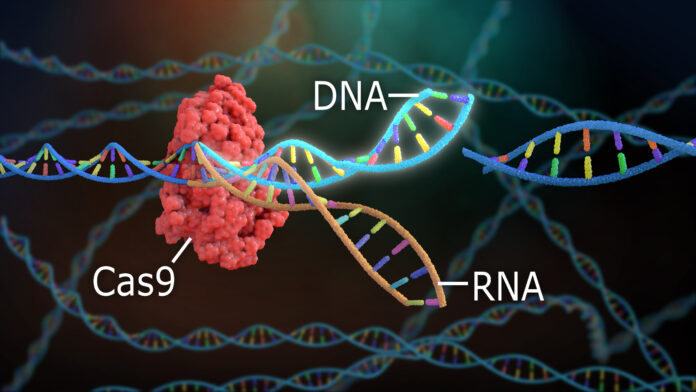

HIV evades the immune system and antiretroviral therapy by hiding in tissue reservoirs potentially for years. EBT-101, which is based on the gene-editing technology CRISPR, removes HIV-infected DNA from human cells.

On a cellular level, the gene-editing therapy works with the help of synthesized compounds called guide RNA, or gRNA. The gRNA identifies regions in the targeted gene that need to be cut and rejoined, and an enzyme called Cas9 does the cutting.

“HIV integrates into the host genome, so parts of HIV or the whole HIV DNA can get into the host genome,” Burdo explained. “That’s really why it’s powerful, because for this strategy you have HIV DNA into the actual cell chromosome. We use the CRISPr/Cas9 with this specific guide RNA, and it tells you exactly where to cut. We look to make sure those sequences don’t have any similarity to any human genes because we want to get rid of the virus, we don’t want to do anything with the human gene.”

Burdo and Khalili successfully tested the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in cells, in mice and monkeys, which is the preclinical work. The team at Excision Biotherapeutics has now brought their work into the clinic where it is being tested in human patients.

“I think we still have a long way before we get to that ultimate step, but we’re taking the appropriate steps along the way,” Burdo said. “I think there’s an aspiration, but there’s also a lot of steps in between.”

One question that Khalili periodically gets, he said, is what happens to the segment of the viral genome that is removed from the cell.

“The question is whether or not that segment can reintegrate in the host genome or some other part,” Khalili said. “So far, we have not seen any evidence for such an event in the cell culture or animal model.”

In terms of the big picture, if all goes well in the clinical trials, Khalili and Burdo hope that the gene-editing therapy can be widely distributed to people living with HIV all over the world. In order to achieve that goal, the scientists set out to make the application of the therapy very simple – a one-shot IV injection of the CRISPR would be all that is needed.

“The reason for that was, we thought that the cure of HIV should not be restricted to the well-equipped hospitals,” Khalili said. “It has to be done across the world, in areas where resources are limited and [cases] are high, like India or Africa and some other places in the world.”

According to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s 2020 HIV Surveillance Report, 18,621 people in Philadelphia were living with HIV/AIDS. The report also shows that in 2020, the largest percentage of newly diagnosed HIV cases were among people assigned male at birth, and men who have sex with men. Non-Hispanic Black people are living with and diagnosed with HIV at disproportionately higher rates than other racial demographics, the report showed.

Nationwide, 1.2 million people are living with HIV, according to 2021 data from www.hiv.gov/. UNAIDS reported that globally, approximately 38.4 million people were living with HIV in 2021 and 1.5 million people were newly diagnosed with HIV that year.

Within the Lewis Katz School of Medicine is the Center for Neurovirology and Gene Editing, where Khalili is the director and Burdo is one of the co-directors. The center is funded by an NIH grant, which includes a community engagement arm, as well as a grant from the Martin Delaney Collaboratory for HIV Cure Research, called CRISPR for Cure.

“We have a big community engagement partner there,” Burdo said. “We’ve had a bunch of meetings, we have a lot of local symposiums, we’ve gone to the Free Free Library of Philadelphia for some events and Strawberry Mansion for some events. We’re trying to have a presence and we’re trying to get the community educated about CRISPR, but also get information back from the community about their feelings of gene editing and the use of that in the community.”

Bebashi Transition to Hope is a partner through the Martin Delaney Collaboratory grant, and the team reached out to Philadelphia FIGHT to potentially form a partnership, Burdo said. Khalili and the team recently had a meeting with the external advisory committee that they developed with partners across the world, not just limited to Philadelphia.

“We are trying to learn from each other,” Khalili said. “On one hand we are scientists, and on another hand there are basically corporate partners trying to help us to solve the problem. And the third part is the individuals who are affected, or they were affected once, or they have sympathy for those people who are affected by the disease. So we are trying to get together and make a nice interactive dialogue in order to move forward.”