By Emily Weiner

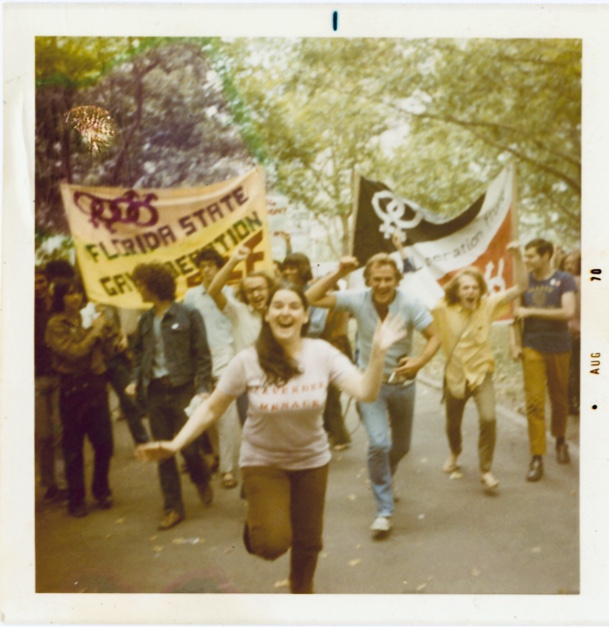

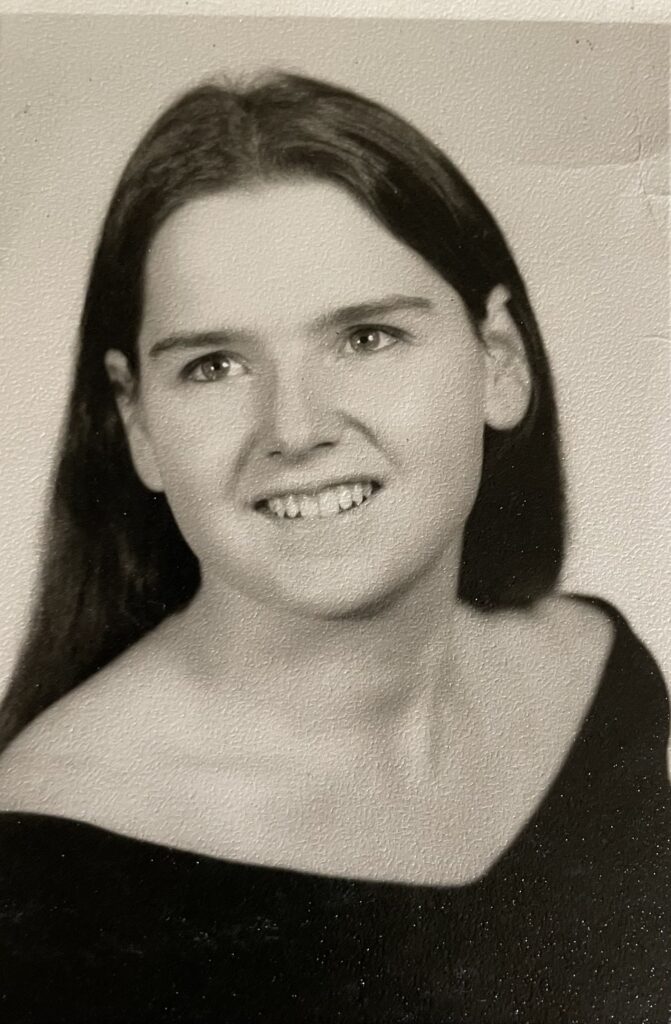

Susan Silverman (aka Susie Silverwoman) died August 24, at age 73, after a short, acute illness and decades of chronic health problems. A memorial service was held August 29 and an obituary was published in PGN.

Susie and I met in 1970 at Alternate U, a free counterculture school and leftist political organizing center in NYC. We became lifelong friends and called each other “sister,” as in “Sisterhood is Powerful!” She named me “next of kin” in her hospital records. (Her three birth siblings are no longer alive.)

In late summer or early fall 1970, Susie asked me to join a lesbian coming-out consciousness raising group she was organizing. I don’t remember where we had met: A women’s dance at Alternate U? A Radicalesbians meeting?

As far as either Susie or I could recollect, at the time there was no such thing as a coming-out consciousness raising group. It is possible that other people created the same type of group in other places around the same time, but we were not aware of any others when we got started. Susie organized our group because she needed it. That’s what organizers do, and Susie was already an organizer.

I was 20, Susie was 21, and the others Susie recruited were around the same age. We had all recently come out as lesbians. Coming out had meanings including having our first lesbian relationship, starting to feel our attraction to other women, or beginning to define ourself as a lesbian — or as a “woman-identified woman,” the term introduced by Radicalesbians (including Susie) in their May 1970 manifesto distributed during the Lavender Menace action at NOW’s Second Congress to Unite Women.

The new gay liberation movement (not yet called LGBTQ+) that Susie had played a key role in organizing immediately following the Stonewall riots in June 1969 was attracting lesbians who had come out years before, as well as newbies like Susie and me.

Susie organized our coming-out consciousness raising group because she was experiencing mistrust from lesbians who had come out before Stonewall — and so she needed to create a community within a community to find support.

Susie wasn’t judgmental of the distrust the lesbians who had come out before Stonewall felt for us newbies, and she understood what was causing it. Lesbians had pretty much all either experienced, or read about, lesbians who had been hurt by women who left their first lesbian lover to be with a man. Many women who had lived for a time as a lesbian had then succumbed to family pressure to marry a man — and that scenario was very often the ending required by publishers of lesbian fiction.

Perhaps Susie not hiding that she had had — and had enjoyed — relationships with men also added to their mistrust. And just being younger than most of the lesbians she was working with in the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and Radicalesbians probably also created distance.

So Susie reached beyond to gather a group of women who were just coming out.

Our coming-out consciousness raising group followed the same structure as other women’s consciousness raising groups of the time. (I was already in one — with mostly straight women — and I believe Susie either had been or still was, too.) We met in each other’s homes, sat in a circle, and took turns speaking about a theme we had previously decided. There was no leader or facilitator. We talked honestly about our relationships: There was one couple in the group, and several new intimate relationships among group members started — and also ended. We talked about sex. We talked a lot about coming out to our families — or not — and about many reasons why we were staying closeted or coming out at work, school, and elsewhere. We talked about the categories of butch, femme, and dyke, and about androgyny — which was how all of us probably were perceived, although reality was way more complicated. We discussed connections between the fight for lesbian and gay rights to feminism and the other liberation struggles that most of us were active in. We cried, we laughed, we shared information, and we offered support.

We also socialized outside of meetings. Susie loved to dance! When we had potlucks, Susie taught us to always label all ingredients in our dishes because at the time she couldn’t eat onions or garlic. (I still appreciate and honor her insistence.) And we participated in political actions; I’m pretty sure we marched together in the 1971 Gay Pride March.

I still can’t believe that Susie is gone, and that she won’t be telling me what to change in how I have written this history. I will miss our weekly phone calls during which we talked about relationships, books, politics, our health — and asked and gave whatever help (or cajoling) the other needed. I miss her wisdom, her friendship, and her love.