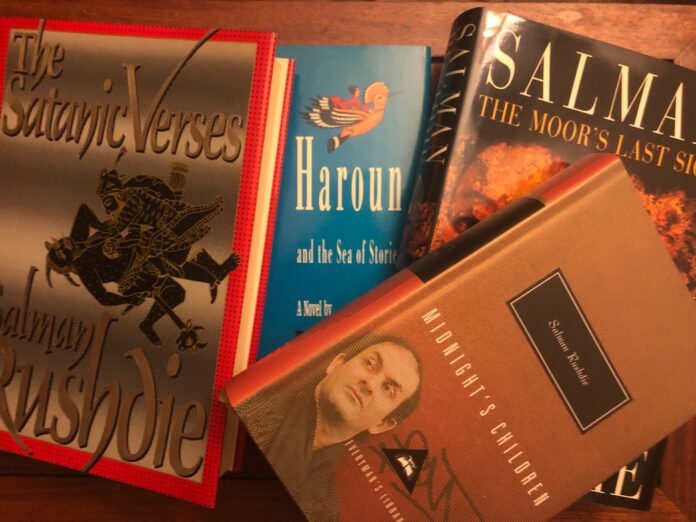

I am spending a quiet Sunday in a little boat on the sea of stories, which is a good thing to do in August, even if prompted by a shock. My favorite author has been savagely attacked in Chautauqua, New York.

Half my lifetime ago, in 1989, The Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against novelist Salman Rushdie, ordering his death for alleged blasphemy in his novel “The Satanic Verses.” My friend Frank Kameny, a gay rights pioneer, then about the age I am now, declared, “What the world needs is more and better blasphemy.” Frank believed that anything that had lasted long enough to become a tradition deserved to be questioned.

In the same year as the fatwa, I met a man from a distant land. He was a devout Muslim, and gay. We met one afternoon outside my office after he made a presentation there for his embassy. He kept his nature a secret from his employer, but it flew as free as a bird across the plaza to me. On our first date, when I ordered Enchiladas Durango (made with chorizo and potatoes in a molé sauce), he asked if it contained pork. I said yes. He said, “But then I can’t kiss you later.” Though I was sure that kissing me was as forbidden as eating pork, I quickly changed my order to something else.

That night was one of the most joyous of my life. Once, after lovemaking, whether that night or another, he whispered to me, “You made me sin.” I happily took full responsibility. But as time passed, his guilt impeded him more and more.

Jay knew who he was, and even volunteered at DC’s Food and Friends preparing meals for people with AIDS. But he had been taught that same-sex love was a sin, and he believed it. I did all I could to help him overcome it, even finding a gay imam who was willing to talk to him. But he refused. He allowed himself only fleeting moments of happiness. Once we went to New York City for a theater weekend. One of the shows was Mozart’s “The Abduction from the Seraglio.” He got back at me later by taking me to see “Jesus Christ Superstar.”

The angriest I saw him was in my bedroom when he spotted my copy of “The Satanic Verses.” By that point, Rushdie’s Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, had been stabbed to death, and Jay fiercely exulted in the murder and said the same fate awaited Rushdie. I insisted that imaginative literature could be no threat to the God who gave us the capacity to create and enjoy it. But Jay was not to be moved.

Love does not always triumph. As much as Jay loved me, he was convinced he was going to hell. I saw him less and less. Eventually he returned to his country. Once he got me to promise that I would take care of him when he grew old. But that was a dream he could not allow himself.

Of course all faiths have their fanatics. Frank Kameny called Christian nationalists the American Taliban. There are progressive Muslims in addition to murderous Islamo-fascists. The sweet man, who left our bed just before dawn, unrolled his prayer mat, put on his kufi, and said his morning prayers before climbing back in beside me, would never have harmed me. All he did was break my heart.

That is my battle scar. Until I die, I will honor it by rejecting fatwas and book burnings and teachers who plant seeds of poison in the minds of children before they even know what it means to fall in love.

Mr. Rushdie was taken off the ventilator after two days and was able to speak a few words. In a statement on August 14, Rushdie’s son Zafar wrote of him, “Though his life-changing injuries are severe, his usual feisty and defiant sense of humor remains intact.”

“Haroun and the Sea of Stories,” published when Rushdie was in hiding, begins with a dedication in the form of an acrostic poem based on Zafar’s name:

“Zembla, Zenda, Xanadu:

All our dream-worlds may come true.

Fairy lands are fearsome too.

As I wander far from view

Read, and bring me home to you.”

In that same faithful spirit, I am dipping into the sea of stories again. That is the only way to turn off the ‘darkbulbs,’ as Rushdie calls them, that would plunge us all into impenetrable gloom.

Richard J. Rosendall is a writer and activist at [email protected].