Many readers of gay fiction no doubt have their likes and dislikes. But one thing on which most of them can agree is that a new novel by Andrew Holleran is cause for celebration. Since the publication of his groundbreaking 1978 debut “Dancer from the Dance,” Holleran has created unforgettable fictional portraits of the emergence of gay life in the novels “Nights in Aruba,” “The Beauty of Men,” the short story collection “In September, the Light Changes,” and the novella “Grief,” as well as in his essay collections “Ground Zero” and “Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath.”

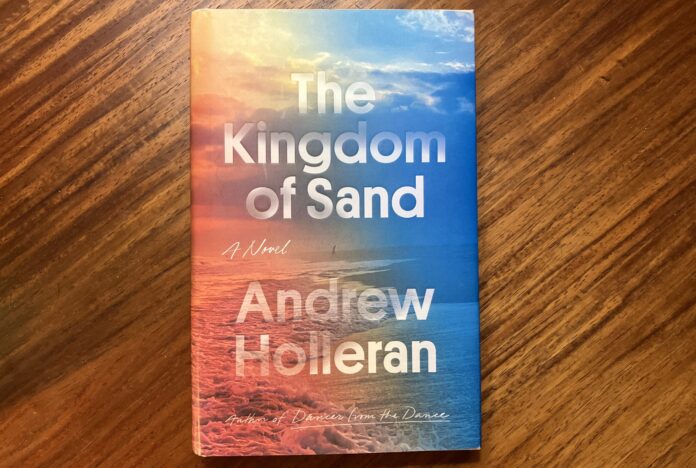

Holleran’s new novel, the Florida-set “The Kingdom of Sand” (FSG, 2022) is a welcome addition to his canon. In the book, the nameless gay narrator confronts the aging process (both his own and those around him) as well as the prospect of what comes after. This is particularly poignant considering how many gay men of Holleran’s generation passed well before their time. Andrew was generous enough to answer a few questions about his new novel.

There are 16 years between the publication of 2006’s “Grief” and 2022’s “The Kingdom of Sand.” Were you working on the latter all along, or did it come about much later?

I was working on other stuff. Kingdom of Sand took about a year and a half, I think, though it incorporated some of the stuff I’d been working on earlier, so I can’t really say how long Sand took.

From my perspective, “The Kingdom of Sand” represents a connection between 1996’s “The Beauty of Men” and 2006’s “Grief,” the way it incorporates Gainesville and Washington DC. Am I on the right track, and if so, is that how you see it?

Yes, there is a connection between, or should I say among, those books. In fact, I think of Kingdom as what happens to the narrator of Grief after he returns to Florida.

Early in the book, the daughter of a neighbor tells the narrator “Everybody here knows you’re gay.” Not long after that, the narrator’s mother asks about his friends, “Why are they all men?” Which leads me to ask, what would it have mattered if he’d come out to his parents?

I have no idea, either in real life or in Kingdom, and that is why the narrator walks out of the room without answering; he can’t imagine the consequences of telling the truth, of coming out. I think this is a conceptual block a lot of gay people have or have had.

In “The Dirty Hat,” the first of five sections in “The Kingdom of Sand,” the narrator details his experiences in an adult video store. There’s a story, “Kid A,” in John Weir’s new short story collection “Your Nostalgia is Killing Me” which is set in an adult booth-store. Would you describe this as a coincidence or a comment on our times?

Well, I do think one of the hilarious ironies of what the Internet has done to our lives — much of it, in my mind, awful — is that one of the chief things people are using it for is pornography! When the narrator in Kingdom goes to the “dirty” video store, he says it’s because he’s been watching so much porn, he thinks he needs to see people having sex in real life. To me, it’s one of those things that is a Comment On Everything. As to why both John and I chose it, I can’t say. It’s either in the Zeitgeist, or it’s some metaphor for gay life, or part of both our lives.

Your Florida observations — including that Florida is “a state where you rarely see anything from a height” — are alternately heartwarming and heartbreaking, especially since I also live here during these challenging DeSantis years. As someone who has a longer history with the state, are you surprised or not by what is taking place here?

I am and am not surprised, though I am concerned, because I have never forgotten the Ray brothers, who got HIV from a blood transfusion years ago, being burned out of their home down in Arcadia, Florida. You can’t make this up! That is, I’ve always been aware that there are two cultures in Florida… actually, many more, but in this case, I’m referring to the native, Protestant, rural, conservative bedrock — versus the invasive species: retirees, snowbirds, etc. — which makes Florida both a “cracker” state and an extremely heterogeneous, multicultural one. The former has always been there and was exemplified a few decades ago not only by the treatment of the Ray brothers, but when the U.N. wanted to designate the St Johns River some version of a UNESCO world culture site or something like that, and people protested because they thought that would cede control of Florida’s government to the U.N.! I thought, “That’s looking a gift horse in the mouth.” And now we have a resurgence of that segment of the culture in DeSantis’ obvious appeals to the Trump base, though, of course, it could be sincere on his part. But these two Floridas are always going to be in contention, I think. But let’s face it: at this point, Florida is a long, long way from its roots.

We’ve talked about movies many times; we both share a love of the medium. Movies are a central part of “The Kingdom of Sand.” Are the movies you mention in the book favorites of yours, and would you say that you are subliminally making recommendations to the reader?

Actually, it occurred to me too late that I could have used those movie lists as a way to push my own favorites. But I didn’t because I wanted the movie choices to characterize (the narrator’s friend) Earl, and his generation, to summon up a vanished USA. There were so many movies Earl shows the narrator that the narrator has never heard of, with actors Earl knew from his own youth; it’s a generational difference, and therefore a difference between two Americas, Earl’s, and the narrator’s.

If there was a movie version of “The Kingdom of Sand,” who would you want to play the narrator?

I’m so out of touch with current movie and TV-making that I have no idea [laughs]. I leave that to you!

Many writers, including Henry James, George Santayana, and Anton Chekhov, are also referenced throughout the book. Is this the educator in you sharing your knowledge in the hopes that readers will explore some of these writers on their own?

Yes, I think so, though that wasn’t my idea when I wrote the book. It occurred to me that the novel form is so loose at this point, that one might as well do anything one wants, and I thought, “Why hide the narrator’s reading?” Earl reads the Bible and books about the Civil War. The narrator’s reading is all over the place; he has a sort of magpie mind, taking aphorisms from this writer and that — he reads books the way Earl watches movies. He’s got a distressed mind, searching here and there, and coming to no conclusion.

Dogs, including the narrator’s friend Earl’s dog Betty, are also a presence in the book. Is there any chance that you’ve added what the kids today call a “fur baby” to your household?

I love dogs, when they’re not off leash and running toward me with indeterminate intent outdoors, but the moment I realized I could not have a fur baby was when I lived with a wonderful dog whose owner was in the hospital for a month. Sitting at home reading or working on the laptop, I’d look over at the dog and worry that it was bored. So, I’d get up and take him for a walk. And I thought, “If you’re such a people pleaser that you can’t bear the idea of a dog being bored, then I don’t think you can live with one.” Plus, the usual reason: If you have a dog, you can’t travel as freely.

In the titular third section, you write about a “friend in Washington” who called the narrator to ask him for help in teaching a course. Is the friend in Washington based on the late gay writer and educator Richard McCann, and if so, what do you think Richard would have thought of “The Kingdom of Sand”?

That is Richard McCann, and the sad thing is I had so much trouble with this book, that I wish I’d taken Richard up on his offer to read it when I was working on it. But for some reason — a) not wanting to burden a friend with that task, and/or b) thinking I had to solve it on my own — I didn’t take him up on his offer. And you know that Richard would have seen the problems immediately and been of immense help, because he was so, so smart.