The first case of the monkeypox virus was detected in Philadelphia, the city’s Department of Public Health announced June 2. The news comes ten days after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared monkeypox was in the U.S. The Philadelphia case was confirmed by CDC testing on June 3.

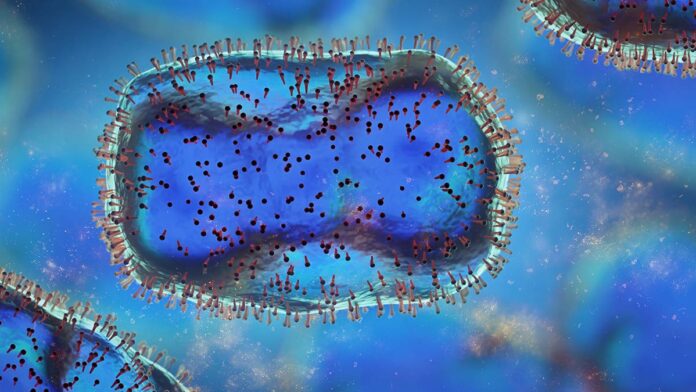

According to the CDC, “Monkeypox is a rare disease that is caused by infection with monkeypox virus” and “the monkeypox virus belongs to a genus that also includes variola virus (which causes smallpox), vaccinia virus (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox virus.”

Monkeypox is spread through close, personal contact. Symptoms usually include fever, fatigue, headache, and enlarged lymph nodes.

According to Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH), city officials are working with the CDC to determine how the person with the confirmed case of the disease was exposed to monkeypox and how and in what ways that person could have exposed others in the time since they became infectious.

“The threat to Philadelphians from monkeypox is extremely low,” said Health Department Acute Communicable Disease Program Manager Dana Perella in a statement.

“Monkeypox is much less contagious than COVID-19 and is containable particularly when prompt care is sought for symptoms. Vaccine to prevent or lessen the severity of illness is available through the CDC for high-risk contacts of persons infected with monkeypox, as is antiviral treatment for patients with monkeypox.”

The PDPH “strongly recommends that anyone who is experiencing symptoms of an unexplained rash on their face, palms, arms, legs, genitals, or perianal region that may be accompanied by flu-like illness should contact their regular healthcare provider as soon as possible. People who are feeling ill should stay home.”

The Health Department adds, “And of course, remember that persons who only have flu-like symptoms without rash should get tested for COVID-19. Ill persons should wear a mask when seeking care or if they are not able to isolate from others.”

Perella added, “I believe that residents and visitors should feel safe to do all the fun things Philadelphia has to offer, with the proper precautions.”

The PDPH said to protect the infected Philadelphian’s privacy, no specific data on their case would be released, but added that the individual is currently working with the Health Department to identify any contacts with others that may have created exposure. PDPH will contact anyone at risk of infection directly.

PDPH added that because the monkeypox virus has a much longer incubation period than many other infectious diseases, contact tracing and containment are more reliable.

“Typically, someone will develop symptoms between five and 21 days from the time that they are exposed,” said Perella.

Perella also noted that a vaccine is available that lessens the severity of illness and that there is also antiviral treatment for patients with monkeypox. There is no cure for monkeypox.

As of 2 June 2022, 780 laboratory confirmed cases of monkeypox have been reported to or identified by WHO (World Health Organization) from 27 countries outside Africa that are not endemic for monkeypox virus, which is endemic to Africa.

The majority of the non-African cases are among gay and bisexual men and men who have sex with other men (MSM), which has prompted concerns about stigmatization of the disease in its current form as a “gay disease,” as PGN previously reported.

Dr. Mark Watkins, an infectious diseases specialist and a provider at the Mazzoni Center who has been in practice for more than 30 years, said, “While most stories we’ve seen about monkeypox focus on outbreaks among gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men, it’s important that we realize this is not a gay infection.”

Watkins said, “Spread through physical contact with the infection’s trademark lesions, it is less contagious than COVID. You’re not going to get it just from casual contact such as walking down the street and bumping past somebody in a crowd.”

Addressing concerns community members and others might have about the disease, Watkins said awareness is key, but contextualizing that awareness is also important. He said, “We need to be aware about monkeypox while not allowing ourselves to become paranoid.”

He added, just days after back-to-back mass shootings on South Street, “Frankly we’re more concerned about gun violence than we are about monkeypox.”

Watkins declined to address Philadelphia specifically, noting that monkeypox is the same everywhere, and thus his statement applies to all cases/places.

Dr. John Brooks, Medical Epidemiologist, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention for CDC, has emphasized that anyone can contract monkeypox through close personal contact regardless of sexual orientation. However, Brooks said many of the people affected globally so far are men who identify as gay or bisexual. Though some groups have greater chance of exposure to monkeypox right now, the risk isn’t limited only to the gay and bisexual community, Brooks said.

Monkeypox is spread through close, personal contact. Initial symptoms usually include fever, fatigue, headache, and enlarged lymph nodes. A rash often starts on the face and then appears on the palms, arms, legs, and other parts of the body.

Some recent cases began with a rash on the genitals or perianal region only with no other initial symptoms. Over a week or two, the rash changes from small, flat spots to tiny blisters that are similar to chicken pox, and then to larger blisters. These can take several weeks to scab over. Once the scabs fall off, the person is no longer contagious.

As PGN previously reported, Monkeypox is a viral disease that is usually found in Central and West Africa. Monkeypox was first discovered in laboratory monkeys in 1958. Blood tests of animals in Africa later found evidence of monkeypox infection in several African rodents.

In 1970, monkeypox was reported in humans for the first time. In June 2003, it was inadvertently imported into the United States in a shipment of exotic African rodents, resulting in transfer of the virus to American prairie dogs with subsequent transmission to humans.

For more information on monkeypox, see the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s newly updated fact sheet.