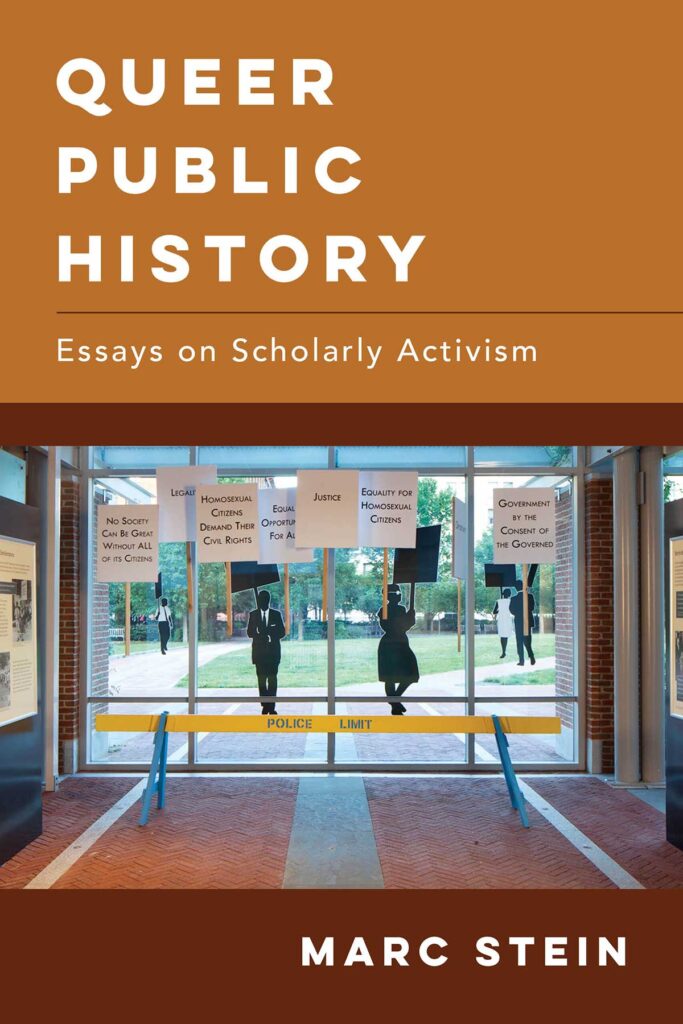

Marc Stein’s new book “Queer Public History: Essays on Scholarly Activism” is a collection of essays that range in topic, including LGBTQ activism in Philadelphia like the Dewey’s Sit-In, the Annual Reminders demonstrations in the 1960s and Kiyoshi Kuramiya’s role in the formation of the Gay Liberation movement in Philly; early and landmark LGBTQ court cases, the beginning of the AIDS crisis, and essays on theories about the Stonewall riots.

In 2000, Stein published the book “City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia 1945-1972,” based on his 1994 dissertation. “I think people who know my earlier book will see some further reflections on Philadelphia history,” Stein said of his new release. “But I think for people who aren’t familiar with that earlier book, my hope is that it captures some of the more significant episodes that I had uncovered in that earlier research.” Through “Queer Pubilc History,” Stein explores the interconnectivity of academic historians and community-based historians, as well as the correlation between LGBTQ historians’ involvement in public domains and the public’s role in influencing queer history.

Why did you write this book?

I guess over the last few years I’ve begun to reflect on my more than three decades of work as a queer historian. I had long been committed to writing not only scholarly work for academic publishers and for professional specialists, but also for larger public audiences. I was really interested in thinking more deeply about the trajectory of over the last several decades in the two areas covered by the book. One is really about the activists’ struggles that were necessary to make a place in queer history within higher education. And the other was how those of us who do queer history have worked, some of us in community-based contexts and some of us in academic contexts to change the public discussion about queer history. There’s been such a dramatic change over the last few decades and there are also great signs of trouble. I thought putting together a collection of my work and then reflecting on the development of the field over my 30 years of engagement would be interesting for me and hopefully interesting for readers.

Is there anything that you came across in your research on Philadelphia LGBTQ activism that surprised you?

My first major project in queer history was my book on Philadelphia, LGBT history from the 1940s to the 1970s. While I was producing this book for a university press, I was also routinely looking for opportunities to share what I was learning in places like PGN and eventually in more mainstream media venues.

There’s been a lot that’s been surprising. I think my work has really documented a more sexually radical pre-Stonewall tradition of activism exemplified by Drum Magazine. I’m really proud of the way that my work uncovered early episodes of trans activism, including the sit-in at Dewey’s. I’m proud of having brought to greater public attention stories of people of color in the movement such as Kiyoshi Kuromiya and Anita Cornwell, and both are covered in the book. Those are some of the things that were reflected both in my 2000 book and my 1994 dissertation that are kind of recaptured in this collection.

Philadelphia has really been in the forefront of landmarking important sites. I supported the nomination of the PGN building; I’ve been so pleased to use my expertise to write letters in support of designating the Camac Baths, the Dewey’s Sit-In, the Annual Reminder. The book also features some photos of those plaques. I really give a lot of credit to local Philadelphians who have taken my research and the research of others and kind of insisted that those sites be identified and publicized, especially Center City is so invested in landmarking historical sites.

My book also does reflect on some problems in the way that that plays out, like the controversy surrounding the Dewey’s marker. [The sign] refers to homosexuals but doesn’t refer to trans people as participating. My work from the get-go, my dissertation, my 2000 book, emphasized how unique and important the Dewey’s Sit-In was because the language of the day referenced masculine women, feminine men, homosexuals and people wearing nonconformist clothing – those were the people who were protesting who were harassed and denied service. By 2022 it’s not really acceptable or accurate to refer to just homosexuals.

The text of the Dewey’s historical marker reads: “Activists led one of the nation’s first LGBT sit-ins here in 1965 after homosexuals were denied service at Dewey’s restaurant. Inspired by African American lunch counter sit-ins, this event prompted Dewey’s to stop its discriminatory policy, an early victory for LGBT rights.”

It’s good that LGBT is used here, but not great that the word homosexuals is singled out.

Can you talk a little more about some of Philly’s community and academic LGBTQ historians?

Two people I think who do the most in Philadelphia currently around queer history are Bob Skiba and John Anderies. They’re both super knowledgeable and incredibly helpful. There’s such a tradition back to the 70s of queer history developing as a partnership between people based in colleges and universities on one hand and then people based in community organizations on the other.

I think nobody did more to preserve queer history in Philadelphia than Tommi Avicolli Mecca, former writer and editor at PGN. He didn’t do it as a professional historian, he did it as an activist and journalist who was collecting historical material along the way and his collection became one of the foundations of the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives at [William Way]. He was doing his thing, while meanwhile in Philadelphia there were people like Carol Smith-Rosenberg, pioneering lesbian historian and Larry Gross who was in communications, Dennis Rubini at Temple. I wouldn’t say that there was that kind of close cooperation and collaboration in Philadelphia necessarily, but there definitely was in places like New York and San Francisco that made a place for queer history at a time when higher education wasn’t that interested. It created these huge audiences for queer history.

How do you think the LGBTQ activism of the past helps inform today’s activism?

It can be trite to say this, but I really do think that we can learn about the present by studying the past. I want to know – how did the world that I’m encountering come to be? Why is it organized the way that it is? Why do we see these injustices? Why do we see these struggles? Why do we see successful forms of activism? I think it can be really helpful to understand our present world. But then there’s the second dimension which is using our past struggles to guide our current thinking about strategies and tactics. That can mean everything from coalitions and intersectional politics versus single-issue politics; strategies based on the politics of respectability versus strategies based on more radical and dissident politics. I think it’s valuable even to think about the domains of struggle. So why is it that in one moment we’re focused on attacking the media, and in another moment we’re focused on attacking the government, and in another moment we’re focused on attacking private business? These are really important strategic questions for movements.

My work is so focused on street demonstrations on the one hand, and court battles on the other. There too I think by studying these past episodes, we can think more carefully and strategically about what’s a moment where we should fight our battles with lawyers in the courtrooms, and what are other moments where we need mass mobilization and street demonstrations. Those things often work in tandem. That’s where if we study the past, when we’re called upon to act in the present and in the future, we can be so much more informed about what worked and what didn’t work in the past.