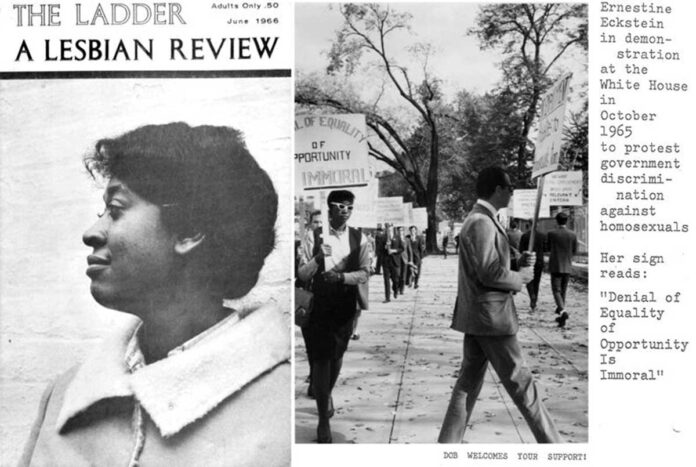

She is the only Black woman in Kay Lahausen’s famous 1965 photograph of the first gay and lesbian picket line in front of the White House. She carried a sign that read, “Denial of Equality of Opportunity is Immoral.” Her name is Ernestine Eckstein.

A year after the White House picket, Eckstein was the first Black woman to be on the cover of the iconic lesbian magazine, “The Ladder,” published by the lesbian political advocacy group the Daughters of Bilitis. One of the only sources of historical material on Eckstein’s life and her politics is derived from an eight-page in-depth interview with the then-25-year-old Eckstein, Kay Tobin (Lahausen’s pseudonym), and Barbara Gittings, Philadelphia activist and Lahausen’s longtime partner and one of the founders of Daughters of Bilitis. The interview appears in the June 1966 issue of The Ladder on which a photograph of Eckstein graces the cover.

The print interview is culled from audio tapes of a long interview in 1965 with Eckstein. Those tapes were unearthed by Making Gay History (MGH) podcast executive producer Sara Burningham. Burningham uncovered a digitized copy of the interview among the archived papers of Barbara Gittings at the New York Public Library.

This deep delve to uncover more about Eckstein points to the critical need for more historical mining of oral histories of those early activists still alive and the crucial need to maintain papers of LGBTQ activists from our pre-digital era.

Born in South Bend, Indiana on April 23,1941 as Ernestine Delois Eppenger, one of eight children of Darnell and Cecelia Eppenger, she adopted the name Eckstein to protect herself from backlash in her job and personal life. In “The Ladder” interview, Eckstein said, “I will get in a picket line, but in a different city.” She knew the dangers of being openly lesbian in those years before Stonewall.

In archival footage reported by NPR in 2019 by gay writer, archivist and host of the MGH podcast Eric Marcus, Eckstein says, “I think it takes a lot of courage. And I think a lot of people who would do it will suffer because of it. But I think any movement needs a certain number of courageous martyrs. There’s no getting around it. That’s really the only thing that can be done, you have to come out and be strong enough to accept whatever consequences come.”

Eckstein was one of those martyrs, and died quite young, just three months after her 51st birthday. Marcus said in the MGH podcast, “She was a visionary. She anticipated, predicted, and foreshadowed so many of the issues that would face the LGBTQ community in the decades to come.”

Eckstein’s early life is filled by Civil Rights activist action. She was a member of Tomahawk, a scholastic honorary society, wrote for the Indiana Daily Student, and was in Singing Hoosiers. She was also a member of Bloomington NAACP. In photographs of her from that time, she is, as she was in Lahausen’s photographs, the only Black woman.

Eckstein says in her interview with “The Ladder” that she graduated from Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana in 1963 with an undergraduate degree in journalism and a minor in government and Russian.

After college, in 1963, the 22-year-old Eckstein moved to New York City where she began attending meetings of the New York Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations.

Eckstein told Lahausen and Gittings that moving to New York City allowed her to come out as a lesbian to herself and to others. That in turn fueled her nascent gay activism. She says in The Ladder that her sexual identity and orientation had always been hovering in the background of her emotional life, but she had no clear articulation of it prior to moving to New York.

Once there, she blossomed. She said, “This was a kind of blank that had never been filled by anything until after I came to New York… I didn’t know the term gay! And he [a gay male friend from Indiana who was living in New York] explained it to me. Then all of a sudden things began to click… the next thing on the agenda was to find a way of being in the homosexual movement.”

Gittings asked her, “Did you know when you came here that you were a lesbian?” to which Eckstein replied, “No, I didn’t. I had been attracted to various teachers and girlfriends, but nothing ever came of it.”

Gittings then asked: “Did you know there were homosexuals in college?”

How Eckstein answered, in her own words, is both powerful and poignant. She said, “It’s very hard to explain this, but I had never known about homosexuality, I’d never thought about it, it’s funny, because I’d always had a very strong attraction to women. But I’d never known anyone who was homosexual, not in grade school or high school or in college. Never heard the word mentioned. And I wasn’t a dumb kid, you know, but this was a kind of blank that had never been filled in by anything — reading, experience, anything — until after I came to New York when I was twenty-two. I look back and I wonder’. I didn’t know there were other people who felt the same way I did.”

She explained, “I used to think, ‘Well, now, what’s wrong with me?’ But at the same time I felt there was nothing unusual about people loving other people regardless of sex. I’ve always believed that love transcends any kind of label — black, white, woman, man. So I didn’t think it was unnatural for me to have reactions to other women. Why not? However, I’d never thought about sexual activities between those of the same sex.”

It was a close male friend from college, who was himself gay, who explained what being gay was to Eckstein when she came to New York.

Marcia M. Gallo wrote in “For Love And For Life, LGBTQ People Are Not Going Back” that Eckstein “had experience working with civil rights organizations such as the NAACP as a college student in Indiana before moving to Manhattan in the early 1960s; she joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) shortly thereafter. She became vice president of the New York Chapter of DOB in 1964 and for the next four years was an influential leader who urged the group and the movement in general to engage in more direct action efforts.”

Eckstein also participated in the “Annual Reminder” gay and lesbian picket protests outside Independence Hall on July 4th in Philadelphia that were chronicled by Lahausen. At those protests, organized by activist Frank Kameny, Eckstein was frequently one of the only women — and the only Black woman — present.

Ecsktein corresponded with Frank Kameny and in his papers are letters between the two in 1965 and 1966. Eckstein wanted Kameny to speak at DOB headquarters to bolster her position that activism and activist strategies and tactics were essential to progress for the lesbian and gay movement.

Ecsktein, writing to Kameny on February 12, 1966, said “I want you to be free enough to say whatever you want, so to speak — about any aspect of the movement. Keep in mind my particular aim: to get these people to realize there is such a thing as the homophile movement and possibly begin to develop a fuller concept of themselves as part of it.”

But on February 17, 1966, Eckstein wrote to Kameny that DOB voted to disinvite Kameny to speak at the organization.

An early activist in the Black feminist movement of the 1970s and the organization Black Women Organized for Action (BWOA), Eckstein had also argued in her interview with “The Ladder” for gays and lesbians to embrace the protest actions of the Black Civil Rights movement.

She told Gittings and Lahousen, “The homosexual has to call attention to the fact that he’s been unjustly acted upon on. This is what the Negro did. Demonstrations, as far as I’m concerned, are one of the very first steps toward changing society. I would like to see in the homophile movement more people who can think. Movements should be intended, I feel, to erase labels, whether ‘black’ or ‘white’ or ‘homosexual’ or ‘heterosexual’. I’d like to find a way of getting all classes of homosexuals involved together in the movement.”

That Eckstein was a profoundly radical and progressive activist is reflected in both her work with DOB and her work with BWOA. Unfortunately little is known of her work post-BWOA, including the circumstances of her death in 1992. But the archive of photos by Lahousen, the extraordinary interview with her, and the extant papers from BWOA illumine a woman of intense commitment and immense drive for the furtherance of equity for gay and Black people and most especially, Black lesbians.

“The Ladder” interview with Eckstein is available online via UC Berkeley Library.