“We’re not like them,” says one man to another, laying atop him on a dirty roadside. “We don’t have as much time — so we’ve got to grab life by the balls and go for it.”

The top in question is Luke (played by Mike Dytri), an erratic, roving drifter, pressing Jon (Craig Gilmore), newly diagnosed as HIV-positive, to stop daydreaming of any kind of normalcy or broad acceptance. The film is Gregg Araki’s cynical, sharp-edged romance “The Living End,” which played Sundance in 1992.

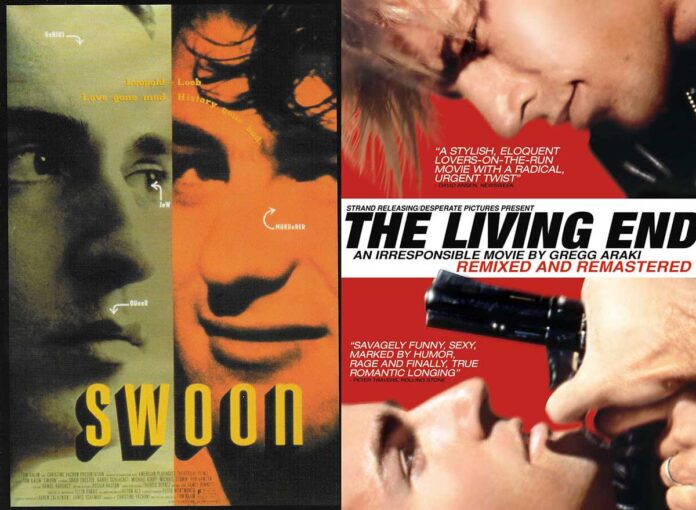

As part of the New Queer Cinema, more a bright moment born of shared circumstances than a movement conceived deliberately, Araki’s film played alongside works by Derek Jarman (“Edward II”), Todd Haynes (“Poison”) and Tom Kalin (“Swoon”) at Sundance that year. Enabled both by the success of Jennie Livingston’s “Paris Is Burning” there the year before and by the new availability of cheap, consumer-grade equipment, these works responded to the violence of the Reagan era and especially the AIDS crisis, with barbed, subversive visions of queer political identity. Whether working in fiction or in documentary, set in America or outside it, the filmmakers pressed ideas of queer experience that hinged on embracing a shared, de facto outsider status with a sense of relish that’s been all too rare in the years since.

According to Hollis Griffin, an associate professor at the University of Michigan in Communication and Media, Sundance helped — as a leader in a blossoming field of film festivals increasingly hospitable to queer work — to give the films it screened a form of credibility that didn’t negate the rebel status they held at that time.

“I think it legitimized [New Queer Cinema] in certain ways. Insofar as Sundance is obviously a major player,” says Griffin of the festival and arthouse film circuit. “It gave New Queer Cinema an exhibition space and an audience that it would not, or might not, have found otherwise.”

Riding a wave of independent productions flowing from the surprise success of works like “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” in the late ’80s, film festivals then helped bring independent — and at times subversive, confrontational — works into public view. In the case of New Queer Cinema (a term coined by the scholar and critic B. Ruby Rich in The Village Voice), this meant exposing them to a new, wider and not solely queer audience, a function different from that of explicitly queer film festivals. This all happened at a time when a home video market existed as more than just a niche, when underground and arthouse cinemas could still have genuine hits, and film held a more central place in global culture than it does today. These realities broadened the number of ways that low-budget work could gain commercial footing. In this climate, a wave of queer filmmakers largely disinterested in profit acted with a sense of uncommon abandon, resulting in more creative, fiercely personal work.

“In the ’90s, we were more sort of experimental and weren’t really thinking about things like: ‘Oh, this movie is going to be a stepping stone to my Hollywood career.’ It was more like, ‘This is the movie I want to make and I don’t care if it makes any money or anything.’ For me, that’s the kind of filmmaking I like; that’s what I still do,” says Todd Verow, whose oft-protested adaptation of Dennis Cooper’s “Frisk” played at Frameline and Sundance a few years later. Since that time, he’s worked under the aegis of his own production company, the New York-based Bangor Films.

But in the case of New Queer Cinema, this disinterest in a market (even as it gained one) proved aesthetically freeing. When Luke, Araki’s drifter in “The Living End,” says “I don’t care about anything anymore” or waves a gun around, it’s not just posturing, even if the feeling may pass. His sentiments are voiced from a place outside the bounds of mainstream society, requiring an acceptance of a kind of precarity mandated from the highest levels of power in the world on down. This kind of existential recklessness born of circumstance colors a hearty portion of this work, and with good reason; for Araki’s peers Marlon Riggs and Derek Jarman, the AIDS crisis ended both their lives and careers, and such specters hung over the movement as a whole.

“I think it was about an urgency to make work and to not conform or try to get money to do it, just to use whatever means you have available and make the work that you want to make,” recalls Verow of working at that time. “It was about not making compromises for a mainstream audience or a straight audience, or you know, the marketplace; it was about making work that was important, or political or artistic, that didn’t give a fuck about making any money or getting any money to make it. Because of AIDS, I think there was an urgency to get work done.”

But these works didn’t just magically appear. They emerged from global aesthetic traditions influenced not just by Hollywood or the more pop-subversive work of Jean-Luc Godard, but by gallery-based and underground filmmaking, which had long carved out niches hospitable to queer work, and which included a range of filmmakers Verow cites as precedents to his own artistry. Kenneth Anger, John Waters, the Kuchar Brothers, Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey figure for him and others as influences – as did the German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder. For a crop of directors straining to make something from almost nothing, there were ample lessons in these directors’ work.

“Coming from a sort of underground, low-budget [production], everyone’s sort of pulling their own weight and more: filming outside in a street without permission and using the headlights of cars to light exterior scenes, just having to work with what you got. And also shooting on film, so you can’t just shoot endlessly and have got to plan stuff out,” says Verow when asked what tied together New Queer Cinema works. “I think it’s a sort of underground punk-rock aesthetic — but queer — that united them all, really.”

In response to the same, Griffin points to those working methods but also to a shared set of thematic preoccupations:

“From the vantage point of 30 years later, the stuff I find interesting about New Queer Cinema is a real attempt to square with history, and with systems of representation. [Cheryl Dunye’s] ‘The Watermelon Woman’ and [Isaac Julien’s] ‘Looking for Langston’ are attempts to think about Black queer history, and to think about Black queer history and its relationship to dominant systems of representation,” he says, voicing an admiration for a recurring investment in “the problematics of history” as a way of grappling with identity in complex ways.

Griffin also points to Tom Kalin’s “Swoon,” a charged and graphic examination of the doomed romance between Leopold and Loeb, two real-life child-killers, as a demonstration not only of New Queer Cinema’s preoccupation with history, but of its willingness to confront viewers with the ugly, frank and often kinky sides of intimacy and desire: a stark contrast to more congenial, flattering efforts in queer representation today.

“Everything has to be pleasant and loving, kind and politically progressive in all of the conventional ways.” But that contemporary vision of queerness comes, says Griffin, “at the expense of understanding desire and sexuality as bound up in not-necessarily pretty, progressive things.”

“Desire can be really dark,” he continues. “Desire undoes the subject and sometimes in wonderful, world-making ways. But I don’t think that we’re living in a moment that can handle a lot of times a complicated take on sexuality, that would understand desire as a complicated category.”

In the past few decades, says Verow, it’s not just audiences but festivals, too, that have become more orthodox and even chaste in their aesthetic tastes. Much of the shift, he suggests, comes from an effort to appease imagined audiences.

“All the rough edges [of a film] have been smoothed away by going to labs, getting opinions from other people. So you’re left with the sort of shiny, happy end product that when you started out was [once] maybe a lot more interesting and dark and had something to say. I think that’s the main compromise,” he observes. “I think if you’re doing things really independently that you’re not thinking about the audience – you’re thinking about the film that you want to make.”

While the endpoint of New Queer Cinema can certainly be debated, its moment seems to have dissipated now. Though Griffin’s unresolved on just what caused this, he observes that it may have created a market that was quickly overrun by more commercialized production.

“I think there was a desire to stay an outsider in New Queer Cinema, and there was never the claim to cultural centrality or the desire to claim cultural centrality in the kinds of media that followed in the years after,” says Griffin. “New Queer Cinema created a consumer demographic that then was infiltrated by more commercialized cultural production.”

The suggestion is that these small, scrappy, early ’90s works couldn’t compete as time went on with bigger-budget material in a market they basically created. The “Milks” and “Philadelphias” and “Birdcages” that came just a few years later were works that showcased queer life, sure, but they had bigger budgets and fewer subversions, and so lacked a lot of New Queer Cinema’s rough edges. They didn’t speak in the same way from a marginal place situated on the roadside: one off the beaten path of accepted mainstream culture. Whatever gains might have been made in negotiating for those gentler textures and trade-offs in representation, something was lost, says Griffin.

“At the end of the day, queer sexuality is fists and spit and overturning staid ideas about what bodies do, what identities do. You sacrifice something with a ‘Love, Simon.’ You sacrifice a more capacious understanding of the body’s relationship to the world, the body’s relationship to power, the body’s relationship to desire, when you stop at them holding hands on the Ferris wheel. You just do,” Griffin says. “And I’m not saying that there’s no place for it. But I’m saying that that can very conveniently become an endpoint in ways that are stultifying.”