My parents were Civil Rights workers and co-founders of the Philadelphia to Philadelphia Project, an interracial group that operated between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Philadelphia, Mississippi. I learned activism from watching my parents and the Black men and women activists who came in and out of our home.

I was too young then to understand the import of meeting those people from SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). I didn’t even understand that other white children were kept largely segregated from Black people. I would learn.

So for me, Martin Luther King Day is a somber holiday — a day of reflection as well as a day of personal memories. I always reread Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” a cautionary tale for white people who credit themselves as allies against racism. That essay — with all its warnings about the perils of the “white moderate”–people like Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who say one thing about equity but do another — remains as urgent now as it was in 1963. The Voting Rights Act, first passed in 1965, is now being legislated again as I write this.

“Letter from a Birmingham Jail” tells us how to be activists, how to be allies and how to deal with the people who are our friends who are complicit as we are victimized. “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

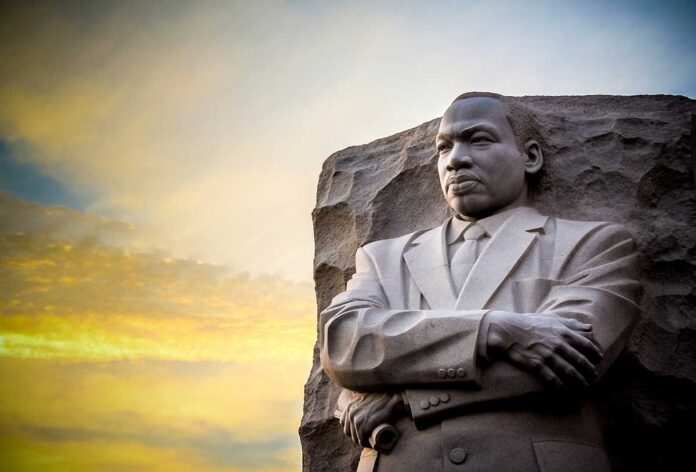

The flurry of politicians on both sides of the aisle quoting Dr. King abated at the stroke of midnight on Tuesday, but days later I’m still revisiting King’s writing. We have much to glean from his eloquence and passion, his forthrightness and his brave intensity, his willingness to risk death so that Black Americans — his four children among them — could be free from the chains of hate. He remains an iconic activist model.

Without even knowing it, my earliest years were forged by King’s actions and his message, and by my 20-something parents who were his acolytes.

I sat on the floor of our living room at the feet of these activists, eager to please — stuffing envelopes and sorting flyers — doing whatever a small child could do in service to an adult movement. One of my mother’s closest friends was perhaps my first crush. A Black woman activist from Mississippi, she would stay at our house when she was in Philadelphia.

Hilda was tall, maybe six feet, and made taller by the stiletto heels she always wore and her hair piled up on her head in a French twist. She was, to me, movie-star elegant. I loved her fiercely. When she stayed with us she slept in my bed and I slept on the floor in a sleeping bag. She was funny and had a low, deep laugh that resonated.

But whenever she stayed with us, our cat had to be kept in the basement because she was afraid of cats. One night it was snowing outside and my bedroom had that blue-white light in the darkness from the cast of the snow. She and I were both awake and I asked her — in the raw way children do — how she could be afraid of a cat when she was so tall and they were so small.

I heard the intake of her breath. She was probably wondering if the little blonde white girl lying in a sleeping bag on the floor was old enough to understand the breadth of the violence of racism.

She decided to tell me.

It was a simple, horrifying tale. One day some white boys grabbed her and put a potato sacking bag over her. She was only a little older than me, she said. The bag covered her completely and she couldn’t get out of it right away.

She wasn’t alone in the bag, though. They’d put a cat in it. And the cat wanted to get out even more than she did. Outside the bloodied, screaming darkness of the bag, the boys were laughing and shoving her to further rile the cat. She was badly clawed and scratched before she could break free.

That was why our cat stayed in the basement when she came to visit us. The scars from the attack were still finely etched on her beautiful face and long, graceful arms. But the trauma remained alive in our little gray cat.

That story, and all the other vicarious experiences of my parents’ activism, created the template from which my own lifelong activism would be forged. That is where I learned that not all of us are equal, a reality I’d soon come to live as a young lesbian.

Dr. King wrote, “Lamentably, we know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

This speaks directly to us as LGBTQ people who still are not equal in society. People still think being LGBTQ is a choice. People still think our being married or having children is immoral and dangerous. People think it is okay to deny us services and accommodations–even medical care–or to fire us from jobs or refuse to hire us. Anti-LGBTQ hate crimes are wildly disproportionate to our demographic. Trans women are killed at a stunning rate. Decades in, the Equality Act has yet to pass to protect us.

In 2022, the GOP has made attacks on LGBTQ people a central message heading into midterms in state legislatures and nationally.

Dr. King teaches us how to fight: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” He also reminds us that to refuse activism is to be complicit in oppression: “The hottest place in Hell is reserved for those who remain neutral in times of great moral conflict.”

Well we are in a time of great moral conflict, and we are among the marginalized people at the epicenter of that conflict. Our own LGBTQ freedom has yet to be won, our own justice is still being denied, our people are still marginalized and discriminated against in a myriad of ways, our very lives are at stake.

In the midst of that maelstrom we have our own activist fervor and the many writings of Dr. King, who gave his life in service to his people and his activism. We would do well to read him not just on MLK Day, but now, in the coming weeks and months, to fortify ourselves for the battle we have ahead.