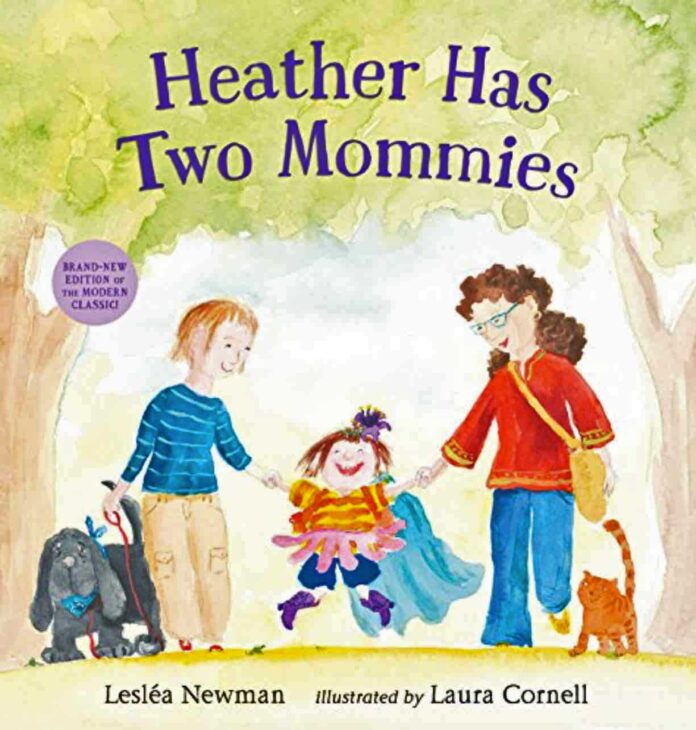

Preschooler Heather is no stranger to opposition. Lesléa Newman’s 1989 “Heather Has Two Mommies,” the first picture book to depict happily coupled same-sex parents and their child, has faced opprobrium from conservatives since it was published. Now, it is one of a record number of other books for children and teens, largely about people with marginalized identities, that are under attack across the country.

In 1992, “Heather” and Michael Willhoite’s “Daddy’s Roommate” (1990) were used as examples of “the militant homosexual agenda” by an Oregon group campaigning to allow anti-gay discrimination. The same year, both books were part of a proposed “Rainbow Curriculum” in New York City about respecting all types of families, but were removed in the face of hostility. “Heather” ultimately garnered a top-10 spot on the American Library Association’s (ALA’s) Most Frequently Challenged Books list for 1990-99. Most librarians supported it though and it mostly stayed on shelves, Newman told me in a 2015 interview.

Challenges continued, however. “Heather” was among the ALA’s Top 100 Most Banned/Challenged Books for the decade 2010-2019, along with more than 20 other LGBTQ-inclusive children’s and young adult (YA) books (which also spoke to the growth of the genre). And this past December, leaders of Pennsylvania’s Pennridge School District removed “Heather” from all elementary school libraries. They also told school officials that all books about gender identity (which “Heather” doesn’t explore) should be removed from shelves and placed in a separate area, only available to parents or guardians upon request, reported WHYY.

This is only one of a rising number of efforts across the U.S. to ban or restrict children’s and YA books with characters who are LGBTQ or people of color or books that deal with topics like gender, race, and racial justice. “We’ve seen a three-fold increase in the number of daily book challenges being reported to ALA compared to the same period last year,” the ALA tweeted on Dec. 30, 2021.

Private individuals and groups, sometimes backed by national organizations with long ties to anti-LGBTQ activism, have made these challenges, but so have elected officials.

Texas State Rep. Matt Krause (R), last October asked schools across the state to tell him whether they hold any of about 850 books that he is concerned “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

And in November South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster (R) asked the state superintendent of education to investigate “the presence of obscene and pornographic materials in public schools,” triggered by parents in one district concerned about “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” by Maia Kobabe, which has also seen bans or challenges in at least six other states, according to a Washington Post article by Kobabe last October. The book has the ALA’s support, however; in 2020 it won the organization’s Alex Award, given to books written for adults that have a “special appeal” to young adults.

Many people are fighting this wave of challenges. In December, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), an alliance of more than 50 national non-profits, released a statement with other LGBTQ, civil rights, faith, literary, and youth organizations, as well as major publishers, book agencies, independent bookstores, authors, teachers, librarians, and others (including myself), condemning the “organized political attack on books in schools.” The statement reads in part: “Libraries offer students the opportunity to encounter books and other material that they might otherwise never see and the freedom to make their own choices about what to read. Denying young people this freedom to explore–often on the basis of a single controversial passage cited out of context–will limit not only what they can learn but who they can become.”

Banning or restricting books because of their characters’ identities or experiences is akin to saying that people with those identities or experiences don’t deserve a place in our communities. Diverse and inclusive books can help young people know they are not alone and guide them in navigating the situations and emotions they or their peers may be experiencing. Keeping such books in schools and libraries is vital, and in some cases lifesaving.

How can we help? This is a multi-pronged problem, but as a start:

- Confidentially report censorship that you see to the ALA and/or to NCAC.

- Buy children’s and YA books about LGBTQ and other marginalized people if your means allow or borrow them from your local library (and recommend them if they’re not there). Share about them on social media and leave reviews at online booksellers.

- Participate in GLAAD’s #BooksNotBans social media campaign.

- Stay tuned in to your local politics and participate in municipal and school board meetings. Vote even in purely local elections.

Let us take heart, too, from “Heather’s” resilience over 30 years and multiple editions (most recently in 2015), and from the flourishing of the genre that she helped propel. LGBTQ-inclusive books for young people of all ages now include characters across the LGBTQ spectrum, and their numbers, once a trickle, have skyrocketed since about 2017. Many have been honored for their literary merits as well as their inclusive content. Books about characters with other marginalized identities have similarly flourished despite obstacles. Opponents will, I hope, find it increasingly difficult to make compelling cases for their removal. That will in turn make it easier for all young people to feel that they belong.

Dana Rudolph is the founder and publisher of Mombian (mombian.com), a GLAAD Media Award-winning blog and resource directory, with a searchable database of 800+ LGBTQ family books, media, and more.