At the time of her death in 1940, Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf had one request: that one important piece of her work not be shared until 50 years after her death.

Featuring ghosts, disgraced alcoholic priests, vagrant cavaliers, wandering immigrants and adventurous young farm boys, Lagerlöf’s work had no shortage of diverse characters. But this work — love letters spanning over 20 years between herself and another woman — showed that the one character Lagerlöf was not willing to publish was her true self. With homosexuality still illegal in Sweden, she hoped the 1990s would be a more accepting time.

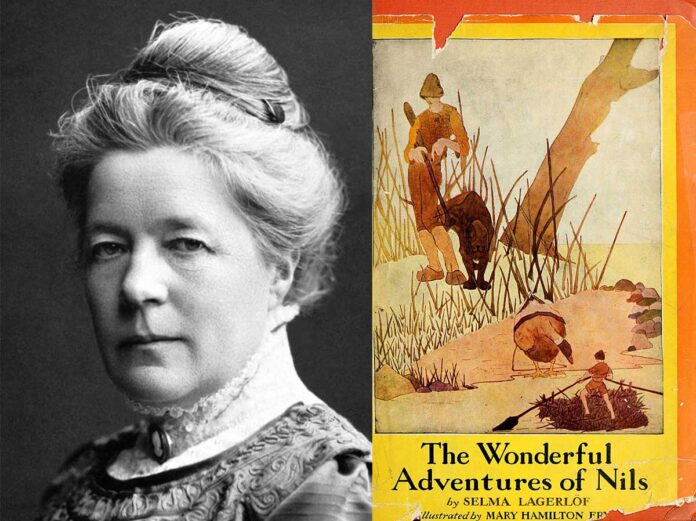

Eventually, the tender love letters between the two women were published, and the world was able to see the affection she tried to hide. Yet, while Lagerlöf had to hide her sexuality during her life, her revolutionary contributions as a writer and active role in women’s rights not only pushed her to become the first woman to ever win the Nobel Prize in Literature, but forever cemented her legacy as a queer, disabled woman who would change the world of literature forever.

A difficult upbringing

Born in 1858 and raised in Värmland, Sweden on an estate called Mårbacka, Lagerlöf’s early life was defined by discipline and religion.

Her father, retired Lieutenant Erik Gustav Lagerlöf, and his wife, Elisabet Lovisa, the daughter of wholesalers, raised young Selma by strict standards. Her childhood was also plagued by illness — contracting polio at the age of three and paralyzing her legs.

Though she was able to receive treatment and walk again by the age of nine, her illness forced her to be homeschooled. She spent her time writing poetry and reading, as well as listening to Nordic fairy tales told to her by her grandmother. The stories of historical battles and exciting adventures sparked a creativity in Lagerlöf — later serving as inspiration for her work.

“For, so long as there are interesting books to read, it seems to me that neither I nor anyone else, for that matter, need be unhappy,” she said.

It was this fervent love for literature, which came amidst her physical ailments, that Lagerlöf said pushed her towards her future career.

“This disability forced me to sit still and look inside myself,” Lagerlöf wrote later in reflection of her early years. “That is why I became a writer.”

Building her voice while meeting her love

The coming years brought hardship and change to Lagerlöf’s life. Her father, who became an alcoholic, died when she was 20 — leaving her family impoverished and the farmhouse she grew up in to be sold.

Leaving home to train as a schoolteacher in Stockholm before working at a school in Landskrona, Lagerlöf’s first success as a writer didn’t come until 1891 at the age of 32.

An intentional rejection of the public’s current interests in realism and naturalism, Lagerlöf’s Gösta Berling’s Saga experimented with lyrical prose and colorful imagination — later becoming a film in 1923. It is considered to be one of her most famous works.

“I have a terribly strong belief in the genius inside me,” she wrote to her mother that same year, already confident the novel would be a success. “I believe that this is the best book yet in Swedish.”

Shortly after publishing a collection of stories called Osynliga länkar, Lagerlöf’s talent in writing was awarded with a scholarship that would allow her to focus on her writing and travel the world.

It was during that time that Lagerlöf met Sophie Elkan, a widow that she would write love letters to until Elkan’s death in 1921. The pair traveled through Europe together, and their trip influenced Lagerlöf’s second book, The Miracles of the Antichrist in 1899 and two-part series Jerusalem in 1901.

At their first meeting, Lagerlöf had already been smitten, lifting Elkan’s veil to say: “You are very beautiful. I know we will become friends.” However, the feelings she had also confused her.

“These kisses of yours that you convey in your letters, they are a great puzzlement to me,” Lagerlöf said. “In Copenhagen, I see so many relationships between women that I must try to comprehend in my own mind what Nature’s intention is with this.”

Over the next several years, Lagerlöf continued to produce novels, short stories, memoirs and nonfiction work — also going on to write a string of children’s books, including The Wonderful Adventures of Nils in 1907 and The Emperor of Portugal in 1914.

Regarded as one of her most influential novels, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils told the story of a boy named Nils who was turned into a mouse and traveled around Sweden. It went on to become an international success read by schoolchildren everywhere.

“So great was Nils’ influence on me that there was a time I could name Sweden’s beautiful locales better than those of my own country,” reminisced Japanese novelist Kenzaburo Oe, during his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994.

Two years after The Wonderful Adventures of Nils was published, Lagerlöf finally won the Nobel Prize after Carl David af Wirsén, the longtime secretary of the Academy at the time, blocked her nomination on five separate occasions.

“He didn’t like new literature and the fact that she was a woman didn’t help,” said Elizabeth Lagerlöf, Selma’s great-niece. “In his opinion, only men should be awarded the Nobel Prize.”

While overjoyed to receive the honor, Lagerlöf’s speech was bittersweet as she imagined how she would come to her father in his rocking chair and tell him of her accomplishment if he were alive. With the money from the Nobel Prize, she was also able to repurchase the Mårbacka estate the family had lost when her father died — and she lived there the rest of her life.

“No one would have been happier than he to hear this,” she said. “Yes, it was a deep sorrow to me that I could not tell him.”

A humanitarian legacy

As World War I began and the women’s suffrage movement ramped up, Lagerlöf continued to work while using her voice to speak up for causes she was passionate about.

While becoming the first female member of the Swedish Academy in 1914, she used her position to fight for the inclusion of more female writers as Nobel winners. During that time, she was also a prominent voice in the women’s suffrage movement until women received the right to vote in 1919.

“Have we done nothing which entitles us to equal rights with man?”,” she asked during her speech at the 1911 international congress on suffrage in Sweden. “Our time on earth has been long — as long as his.”

During this time, though, Lagerlöf published very little work throughout World War I. She published memories of her childhood and a diary of her life in 1930 and 1932 respectively. She also produced an earlier trilogy set where she grew up titled Löwensköldska ringen, Charlotte Löwensköld and Anna Svärd from 1925 to 1928.

Both World War I and II deeply disturbed her, and she donated her work to support Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. She also sent her Nobel Prize medal, along with her Gold Medal from Swedish Academy, to Finland in hopes to raise money to fight the Soviet Union.

Further, after being asked to provide shelter to a Jewish woman, Nelly Sachs, and her mother, the two narrowly escaped to her estate a week before Sachs was meant to be deported to a concentration camp. Sachs later went on to be a Nobel Prize winner herself — winning the Literature prize in 1966.

Dying in 1940, Lagerlöf never got to find out if Sachs and her mother made it to safety. Yet, it was her kindness to Sachs — and general humanitarian spirit paired with her unapologetic style of work — that would allow much of her writing to be adapted into film and her to be remembered long after her passing.

“She remains a living author on every cultural level,” Elisabeth Lagerlöf said.