When Amanda Swiger got married back in April 2014, she and her fiance Jasmine faced struggles some other couples wouldn’t.

With their marriage not yet legal in Pennsylvania, Swiger knew the wedding would have to be in Delaware. And with Swiger’s parents not willing to come to the wedding, she had to do without them on her big day.

Then, when Swiger reached out to one of her favorite photographers to shoot the celebration, she had to find someone else after hearing a resounding “no.”

“Obviously, that was disheartening,” she recalled.

While the barrier that legally prevented queer couples from getting married was lifted over six years ago in the United States, some of the same challenges — including being turned away by wedding photographers — still remain.

That’s why Swiger, along with a small band of other Philadelphia-based wedding photographers, have devoted their careers to fighting the heteronormative stereotypes that pervade weddings and providing inclusive, authentic photos for queer couples in the area.

For some of the photographers, shooting queer couples was something that happened organically. Early on, many of those clients came to them after being turned away from other vendors.

Carina Romano, owner of Love Me Do Photography, said that her business began photographing queer weddings a few years after opening in 2006.

“We were already doing all different sorts of weddings… and to me that’s just a different piece of the puzzle that is humanity,” she said. “It was never like a ‘do I want to do this, do I not want to do this’ it was always like ‘yes of course.’”

Tara Robertson, owner of Tara Beth Photography echoed Romano. When she started her business ten years ago, it felt natural to her to photograph queer weddings as a queer woman herself.

“It just kind of happened that no one was shooting queer couples and no one was definitely shooting queer weddings,” she said. “Right in the beginning it was still so taboo, it felt kind of secretive that we were all gathering to celebrate these two people that were getting married.”

Others like Shannon Collins, owner of Shannon Collins Photography, were also prompted by their own sexuality to photograph LGBTQ clients. Twelve years ago, their first photo shoot was LGBTQ.

“It’s just something that’s always been in my heart,” they said. “I feel like it’s been affirming both on my end and on their end just to be a community together.”

In Swiger’s case, bringing on queer clients is a big priority now, but her business didn’t start out that way. Graduating from a conservative Christian college, she started out shooting weddings similar to that demographic before she came out and married her wife.

Now, for this year, 68 percent of her weddings are queer — and next year that number is 91 percent.

“As I came out of the closet, my business came out of the closet,” she laughed.

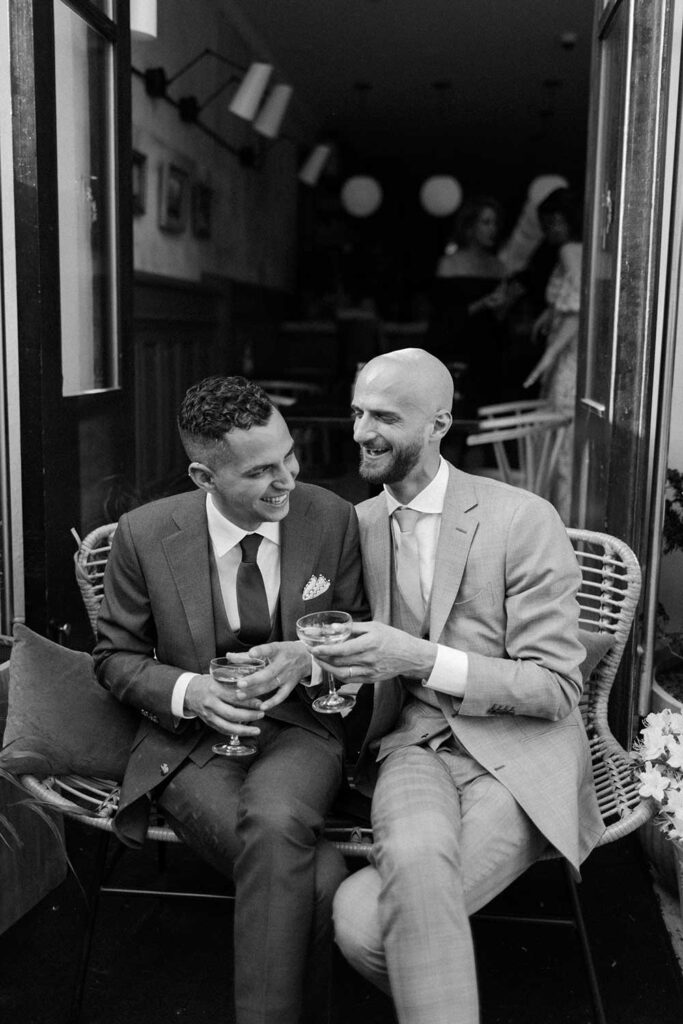

However they got their start, all of the photographers voiced that being inclusive to queer couples is much more than just accepting them as clients.

One big consideration was posing.

A big mistake that some photographers make, Swiger said, is posing couples the same as they would for a cisgender, heterosexual couple.

In photos taken of Swiger and her own wife during their first year of marriage, for example, the photographer tried to assign her wife the more masculine poses because of her appearance — which caused the photos to look forced and inauthentic.

“They just weren’t us,” Swiger said. “At the end of the day, it shouldn’t matter if you’re gay, straight, queer, Black, White, Brown. Every photographer should know how to pose people, and your posing shouldn’t be based on the gender of the couple.”

Inna Spivakova, owner of Peach Plum Pear Photo, said that one way she learns how to pose couples naturally is to pay attention to how they instinctively interact during her engagement session with the couple prior to the wedding

“I just try to watch what couples do naturally,” she said. “I try to, in general, not force people in any specific positions.”

A few other photographers, including Romano, described a similar approach.

“A lot of times, I’m just looking at how they naturally fall into each other,” she added. “Instead of saying things like ‘okay, you lean back into this person’ it’s more like ‘just embrace how you would embrace.’”

Another big factor to take into account is language. Asking for pronouns ahead of time in their contact forms and using them vigilantly with the couple was a common practice among all of the professionals.

Many of them also brought up outdated terms that they now avoid or replace, like using ‘wedding party’ instead of ‘bridal party.’ Those efforts, Collins said, also extend beyond photographers — with many DJs and other vendors making embarrassing blunders like announcing the ‘bride and groom’ at a queer wedding.

“There’s so many ways to reinvestigate what language we’re using,” Collins said.

Other factors the photographers found important were being sensitive to family not being present and providing extra support to the couple if needed.

“The family dynamic that still exists today amongst queer couples tends to make it a bittersweet situation,” Robertson said. “There is a tinge of pain and heartbreak when you go to some of these weddings.”

Spivakova agreed.

“It’s heartbreaking to see,” she said. “Hopefully the next generation will not have issues like that to deal with.”

Despite all of the additional factors, each photographer brought with them fond memories of queer weddings past.

For Robertson, a great memory was running down to city hall on the day same-sex marriage was legalized to photograph all of the couples getting their nuptials. For Collins, that was a recent lesbian wedding that featured a joyous second line.

And Swiger reminisced on an elopement of a couple who got married at Yale University just twenty feet from a religious protest.

“It was a whole body chill moment of listening to these two beautiful humans profess their love for each other with the background noise of all this hatred,” Swiger said. “That’s to me, though, what’s like being a queer person in this world — is that our love has to shine brighter.”

To Robertson, ceremonies like those demonstrate how sacred and special queer weddings can be. The realization that their ceremony would not have been possible just a few years ago is not lost on them, she said, whereas straight couples don’t have the same sense of the significance.

“I think that queer couples truly honor marriage more than straight couples,” she said. “That’s a huge statement I know that I’m making, but after seeing these couples get married, I truly believe that.”

However, with the existing roadblocks still in place, all of the photographers had high hopes for more inclusivity for the future of the wedding industry.

For Collins, moving towards inclusivity in the business as a whole starts with holding themselves and other vendors accountable to constantly improve.

“[I’m] trying to break down those walls, and make people feel more affirmed in their identities,” they said. “And making space for them and celebrating them along the way.”

As for the industry as a whole, it was the hope of many of the photographers that people make sure to educate themselves more and truly take the steps necessary to celebrate queer love the way it deserves.

“I think that, going into 2022, we all need to grow, we all need to expand our opinions on what it means to get married,” Robertson said.