There have been significant LGBTQ films throughout history starting back in the silent era when Germany produced the films “Different from the Others” (1919), “Michael,” (1924), and “Sex in Chains” (1928). And there have been historically significant LGBTQ films, from “Philadelphia” (1993), the first Hollywood film to address AIDS, to Philadelphia native Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman” (1996), the first film directed by a Black lesbian filmmaker.

But every moviegoer has their own personal history — films they saw that were historic or significant to them. As someone who started watching films seriously in my teenage years (the 1980s), and in a time when LGBTQ films were rare to see (and largely portrayed queer characters as stereotypes or in negative light), the films that made an impact on me were especially significant. Call it my own queer film history.

As a teen, I sought out films with gay characters, often secretly. “Midnight Cowboy” struck me with its homoeroticism when I saw it on broadcast TV in a basement. (The gay sex scene was surely deleted for airing.) “The Boys in the Band” (1970) was one I rented from the video store and I was struck by its power. “Making Love” (1982) played endlessly on cable and I saw it as often as I could, studying it intently.

I would venture out to see queer films in the theater too. “Come Back to the Five and Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean” (1982), was a film I went and saw twice because it absolutely mesmerized me. (It’s on the Criterion Channel this month). “The Fourth Man” (1983), was shockingly sexy and violent, and I still have vivid images from it burned in my head. “The Times of Harvey Milk,” (1984) inspired me and introduced me to real life gay heroes. I also recall being obsessed over “Kiss of the Spider Woman” (1982) and dropping my popcorn at “Law of Desire” (1987) with its memorable opening scene.

The TLA on South Street was a revival house back in the day, and I remember going to see “Death in Venice” (1971) with my father, who graciously indulged my interest in seeing it. An even more awkward viewing experience was taking my mother to see “My Beautiful Laundrette” (1985). She thought it was going to be a comedy; I knew it was a stinging social comedy. We still chuckle about this.

But these films, all landmark moments in my salad days, only exposed me to the power of queer cinema and the importance of LGBTQ visibility and representation. Moreover, they prompted me to search out more.

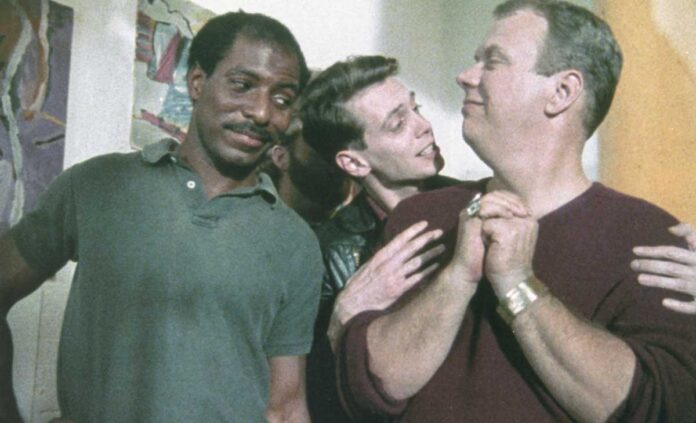

I remember seeing “Parting Glances” (1986) in college. It may have been the first time I really felt I saw myself on screen. I deeply identified with Michael (Richard Ganoung), the main character who had a publishing job, a handsome blonde boyfriend, a coterie of great friends, and a dear (if alas, dying) best friend. It was kind of how I imagined my future life to be and, truth be told, pretty close to how my life turned out. I revisit this film from time to time, as it gives me such comfort. “Parting Glances” was sadly the only feature directed by the late Bill Sherwood, who died from AIDS. (The film was one of the first to feature a character with AIDS). It was a watershed film for me in a different way. I recall telling members of my family that I’d seen it, a way of coming out, as it were.

As independent queer cinema started evolving and improving, New Queer Cinema burst on the scene and I was easily in my element checking out all of the in-your-face films like “Poison” (1991), “Swoon” (1992), “The Living End” (1992), and “Frisk” (1995).

But even as films got radical, there was still the sensitive cinema I also craved. The “Boys Life” short film program (1994) was a marvelous showcase that featured “three stories of love, lust, and liberation.” It not only sparked my interest in queer short films, but I felt a connection with the young gay male characters seeking a sense of belonging on screen.

In contrast, “Edge of Seventeen” (1998) was an intensely personal film that was too painful for me when I first saw it. I certainly recognized parts of myself in the lead character, Eric (Chris Stafford), but the film struck such a nerve that I disliked it. It was too truthful. When I rewatched it later, I saw “Edge of Seventeen” for the masterpiece of coming out/queer coming-of-age it is.

Lastly, another coming out/coming-of-age film, “Come Undone” (2000), was pivotal in my queer film history. I greatly admired this French film about two gay teenagers, and certainly appreciated Mathieu’s (Jérémie Elkaïm), struggle with his sexuality. But what makes “Come Undone” historically important for me is that it was also the first review I published in PGN.