Deemed the “Happiest Place on Earth,” Disneyland sadly didn’t live up to that billing for same-sex couples during its first three decades. Opened in 1955 by the late Walt Disney, the family-oriented amusement park was built on a former orange orchard in Anaheim, California.

Two years later, with it launching “date nights” that featured dancing under the stars to lure local Orange County couples, especially teenagers, on weekends, Disneyland management adopted a strict policy for who was allowed to show off their dance moves. The rule made clear that “couples only are allowed on the dance floor (male/female)” but did make an allowance that “small children may dance as non-couples if floor space permits.”

The park’s security officers strictly enforced the homophobic policy, quickly breaking up any couple that deviated from it. So was the case when a young lesbian showed up at the park in 1980 and was told she couldn’t dance with other girls.

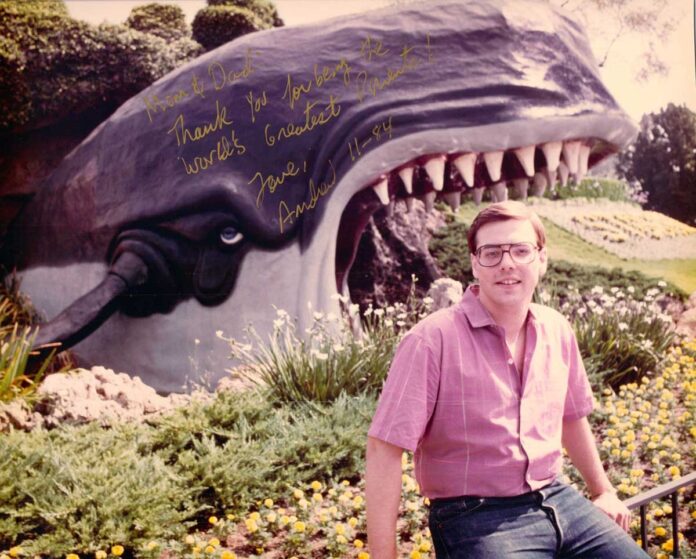

Her roommate at the time was Andrew Exler, who had grown up less than two miles from Disneyland and often attended the theme park, even at times skipping school to spend the day among its fantastical lands. A young gay activist who had already tangled with his local school district over its censorious policies pertaining to students who wanted to provide public comment during school board meetings, the 19-year-old Exler sprang into action.

He wrote and called Disneyland executives to raise objections about the dancing restrictions. Disappointed in the response he received, Exler enlisted a 17-year-old Shawn Elliott, another gay teen he had befriended at their local LGBTQ community center, to help him protest the policy during date night on Saturday, September 13, 1980.

None of the local reporters Exler had contacted to give them a heads up agreed to document their dance floor rebellion, telling him they doubted park employees would do anything so harsh as to kick them out of the park. Undaunted, and clad in a dragon-adorned light blue kimono he had bought at a Judy’s department store “Gear for Guys” section — “we called it Gear for Gays,” he recalled — Exler arrived at the park that evening with Elliott and headed to the Tomorrowland Terrace in the space-themed land of the park to join the dance floor.

“I probably sticked out like a sore thumb. Shawn was in more normal stuff,” recalled Exler, 60, who legally changed his name to Crusader in 1995, in a recent phone interview with the Bay Area Reporter.

The pair of platonic friends soon were grooving to disco tunes along with the other dancing couples. Never did the young men touch each other or embrace for a slow dance, as Crusader noted in a guest opinion piece published in the October 17, 1991 issue of the B.A.R. marking the 11th anniversary of their ejection from the park.

“Our crime was disco dancing,” he wrote. “We didn’t touch, we didn’t kiss, we didn’t bump and grind. We simply danced to the sounds of some horrible disco band.”

Nonetheless, it didn’t take long for park security officers to approach them and demand they leave the dance floor or find girls to dance with them. Security officer William Acker would later recall that he told the teenagers their dancing together “was of a controversial nature at that point, and I believe specifically I said something to the effect of alternate lifestyle that wasn’t in keeping with the traditional aspects of the company, of what Disneyland represents.”

Crusader remembers one security officer tried to break up the two teens by standing in the middle of them.

“I danced around him. I just moved and danced around and got to the other side of Shawn,” said Crusader, who was living in Fullerton at the time and working for Orange County.

By then five security officers had surrounded them on the dance floor. One grabbed Crusader on his left side, another grabbed him on his right.

“They brought me to a complete stop,” he said. “They escorted me and told Shawn to follow your partner.”

After a brief exchange near the dance floor where the security personnel explained the park’s ban on same-sex couples dancing, the friends were led to the front entrance to Disneyland. They held hands as they walked down the park’s Main Street.

“People must be thinking, ‘What the fuck did they do?’ In the security office they interviewed us to get our names, addresses, ages,” said Crusader. “Then they said you can stay tonight in the park as long as you don’t dance together. We said nothing doing, we don’t agree to that.”

While they were told they had to leave and couldn’t return that night, Crusader remembers being informed they would be welcomed back any other time. The next day he granted an exclusive interview to a Los Angeles Times reporter, and her story was featured in the Monday edition.

Lawsuit filed

It resulted in a flurry of local press coverage, and the two teens sued Disneyland claiming its same-sex-dance ban violated their rights under California’s Unruh Civil Rights Act. The nondiscrimination code applies to businesses serving the public and at the time expressly prohibited discrimination in public accommodation based upon sex, race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, disability, and medical condition.

As detailed in their lawsuit filed September 22, 1980 with the Orange County Superior Court, the two friends “desire to return to Disneyland and to consensually dance with other males on the dance floor but are prevented from doing so by Disneyland’s enforcement of its no-same-sex-dancing policy.”

Taking the case was attorney Ronald Talmo, a straight ally a few years out of law school with a solo practice who had worked with Crusader on a free speech lawsuit against the local school district. Speaking to the B.A.R., Talmo said he did so because he was confident they had a compelling legal argument.

“It was blatant,” said Talmo, of the discriminatory policy Disneyland was enforcing. “The idea was even though you are a place of public accommodation and think you can exclude whoever you want, you can’t.”

No one thought he and his clients had a chance in court. Other gay people told Crusader he was “too flamboyant” and shouldn’t be taking on Disneyland.

“The Disneyland case, the gay community didn’t give two shits about,” he said, as it received little coverage in the gay press at the time.

Fellow lawyers told Talmo they didn’t think he could win, and a lesbian attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Los Angeles office tried to persuade him to drop the case for fear it would set back the fight for gay rights.

“Other lawyers told me I was nuts to take it,” said Talmo.

Taking on a giant

Reflecting its clout both as a behemoth in the entertainment industry and the largest private employer in Orange County, Disneyland had never lost a legal battle in court. Until then the lawsuits filed against it largely had to do with people claiming they had been injured in the park.

“I was told Disneyland usually was sued 50 times a year since it had opened in 1955. Although it settled a case here and there, which is rare, it never lost one,” said Talmo. “Until ours.”

Initially, it looked like Disneyland would score another legal victory. The state courts declined Talmo’s request for an immediate injunction against the park’s dancing policy, with the case then sent back to the local superior court to be heard on its merits.

A lucky break then came for Talmo and his clients when the scheduling judge in Orange County deliberately assigned the case to Judge James R. Ross, who had practiced law in Los Angeles County. Years later Talmo would learn about the scheduling subterfuge.

“The master calendar judge knows what the case is about. He says, ‘You know I had to decide who to give this case to. The courtrooms open I wasn’t going to send you to because I thought you should win, and I didn’t think you were going to get a fair trial anywhere,’” recalled Talmo.

With an “out of county” judge not from Orange County assigned to the case, Talmo expected that Ross would be the sole person to hear the lawsuit and decide on their injunction request to end the same-sex-dancing ban. Their lawsuit initially had sought $10,000 in statutory damages for the plaintiffs, but Talmo had decided not to seek any money from the company for his clients, which negated the need for a jury.

Yet the lawyers from the firm Disneyland hired to defend it — Hill, Farrer & Burrill — surprised Talmo and Ross during their first meeting about the lawsuit by pulling out a 28-page brief arguing to have an advisory jury weigh in on the case. The jurors would proffer a decision that Ross could then accept, or reject and issue his own ruling.

“The judge says, and I remember this really clearly, ‘Let’s impanel a jury, this should be fun.’ That’s how we ended up with a jury,” recalled Talmo.

At first Talmo had his doubts about seating an impartial jury. During juror selection one man who looked to be over 6 feet tall with tattoos covering both his arms told the judge the case offended him as a Roman Catholic.

“I turn to Andrew [Crusader] and say, ‘We are in trouble buddy,’” recalled Talmo, even though the man was dismissed.

Disneyland’s legal team argued that the same-sex dancing prohibition didn’t discriminate on the basis of the teens’ sex or “sexual preference.” Rather they argued it is “a regulation of specific conduct that is rationally related to the services performed and the facilities provided at Disneyland.”

In effect, the lawyers argued that the policy was merely an “innocuous deportment regulation” that meant “no one has the right to dance at Disneyland except upon those terms Disneyland permits.”

Richard Nunis, then Disneyland’s president, had helped formulate the rule in 1957 and testified during the trial that the regulation wasn’t adopted to preclude homosexuals from dancing with each other. Such a possibility wasn’t even discussed at the time, he claimed, and their focus was how to keep the dance floor from being overcrowded.

Nunis explained to the jury that the real concern had to do with pairs of women overtaking the dance floor. Back then, he said, it was common for two women to dance together in public if they had no men to dance with them.

Stunning decision

The jury wasn’t swayed by Disneyland’s reasoning and advised the judge to side for the plaintiffs, which Ross readily agreed to in May 1984. His decision so stunned Talmo that the young attorney began to uncontrollably sob as it sunk in that he had scored a legal victory against Disneyland.

“I started bawling, not tearing up, I am bawling and sitting down. One of the jurors walks over to the witness stand, grabs the box of tissues, and puts it in front of me,” said Talmo. “I never felt pressure from the people telling me to drop it. I didn’t think it had got to me, as I always brushed it aside. Apparently, I hadn’t brushed anything aside. It was just overwhelming, that Disneyland case.”

Disneyland did file an appeal of the ruling. Its lawyers in their August 9, 1985 brief before the state’s 4th Appellate District court referred to various marriage rights cases such as Perez v. Sharp and Loving v. Virginia in making their point that “in California, by statute, people of the same sex do not have the right to marry” nor by extension to dance together at a theme park.

“Homosexuals, as a class, are not barred from dancing. They are simply required to dance in the traditional manner, with partners of the opposite sex, as are heterosexuals and bisexuals,” the lawyers argued, stressing that it applied to every dancing duo at Disneyland. “The rule prevents any same gender couple from gaining access to the dance floor, regardless of the sexual preference of the two individuals.”

Coincidentally, it was another case Talmo had filed on behalf of a man upset at being denied the discounts that nightclubs, bars, and car washes offered women on so-called “ladies nights” that torpedoed Disneyland’s appeal. Three days before they were to argue in that case, the California Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in Koire v. Metro Car Wash that the businesses were in violation of the Unruh Act.

“The impact of that decision is a business’ reason for doing the discrimination does not matter,” explained Talmo.

Thus, Disneyland no longer had a legal defense for why its same-sex-dance ban should be allowed to remain. Its lead attorney called up Talmo to congratulate him on the win in the other case and offered a settlement agreement in Exler v. Disneyland.

The company paid Talmo $25,000 to cover most of his legal fees in the case, dismissed its appeal, and allowed the trial judge’s ruling to stand. Although it only applied to Crusader and Elliott, the ruling did have a wider impact, contended Talmo.

Groundwork for future cases

The company could never again use the same defense in court if it was sued again over its same-sex-dancing ban, he noted, and other businesses were put on notice that they could be held legally liable for their own homophobic policies. In terms of the legal fight for LGBTQ rights, Talmo sees the case as helping to lay the groundwork for rulings in future cases.

“Other than a large corporate American business tried to defend family values in the way they saw the definition of family and they lost, I think it was one of just many small steps that happened accumulatively in California and nationwide,” said Talmo, 70, who is considering retiring from the law next year. “It fits in with the small steps that were made redefining or making a deeper analysis really of what is family, what are relationships.”

According to a story in the L.A. Times, Disneyland relaxed its dancing policy in 1985. Al Flores, a spokesman for the company, had told the paper that because the park’s Videopolis dance club venue was popular with teenagers, “we see a lot of situations where two girls come together and want to dance and ask to. We have always said no, but we changed our minds.”

Yet, in 1988, three gay UCLA students sued Disneyland after they said security personnel stopped them from slow dancing at Videopolis. This time Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, the LGBTQ legal advocacy nonprofit, represented them in court.

According to an OC Weekly story, the suit was dropped after Disneyland pledged it would no longer discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. The newspaper reported that Crusader returned to Disneyland in 1989 with a group of eight male couples who danced the night away without incident.

Hits and misses

Since then, Disneyland and its parent company have become strong advocates of the LGBTQ community, financially donating to LGBTQ causes and nonprofits. It unofficially welcomes LGBTQ attendees of annual Gay Days events at its parks in Anaheim and outside Orlando, Florida, while a few years ago Disneyland Paris become the first of its theme parks to officially sponsor a Gay Days event.

George Kalogridis, a gay man who was president of both Disneyland and Walt Disney World between 2009 and 2019, recently was presented with his own window on a Main Street building at the Magic Kingdom theme park in Florida, one of the company’s highest honors for its employees. Yet Disney and its divisions still have a ways to go in fully representing LGBTQ people on-screen.

While it has touted the inclusion of out characters in several of its movies and animated programming, often they are easy to miss unless the viewer is clued in. In this summer’s release “The Jungle Cruise,” for example, a main character is clearly gay, though the word “gay” or “homosexual” is never uttered.

And Disney continues to face claims of anti-gay bias in court. In June, Joel Hopkins, the vice president of production finance at ABC Signature, alleged in a discrimination lawsuit against the Disney company that the television channel’s CFO, Jim Hedges, ruined his chances for advancement because of his sexual orientation.

As for LGBTQ legal rights in the years after Exler v. Disneyland, the California Supreme Court consistently ruled that the state’s Unruh Act applied to LGBTQ people. State lawmakers codified such rulings in the law with their passage of the Civil Rights Act of 2005. Written by gay then-Assemblyman John Laird, now a state Senator (D-Santa Cruz), Assembly Bill 1400 added sexual orientation, gender, and marital status to the Unruh Act.

Former governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed it into law that September. It went into effect January 1, 2006.

Papers lost

Talmo lost most of his papers related to the Disneyland case when he joined a law firm around the time of the verdict. If anything, he wishes he had a transcript of the trial documenting the moments of levity and hilarity in the courtroom.

“It kills Andrew [Crusader] and I that neither of us have it anymore,” he said. “The court reporter died, so we couldn’t get it from her.”

Crusader, who also waged a successful legal fight so men could attend shows of the male Chippendales dancers, told the B.A.R. he lost many of his clippings and documents from the trial when his storage unit was broken into. Elliott, who mostly eschewed the media spotlight during the trial and thereafter, died several years ago, he said.

Now living in Menifee, California (Riverside County) with his parents after being evicted from his apartment in Palm Springs in 2008, Crusader is a proofreader of court transcripts and depositions for court recorders. He helped promote the very first Gay Days at Disneyland that took place on Saturday, October 10, 1998.

“To my memory that was the last time I went to Disneyland,” said Crusader.

Matthew S. Bajko is an assistant editor at the Bay Area Reporter.