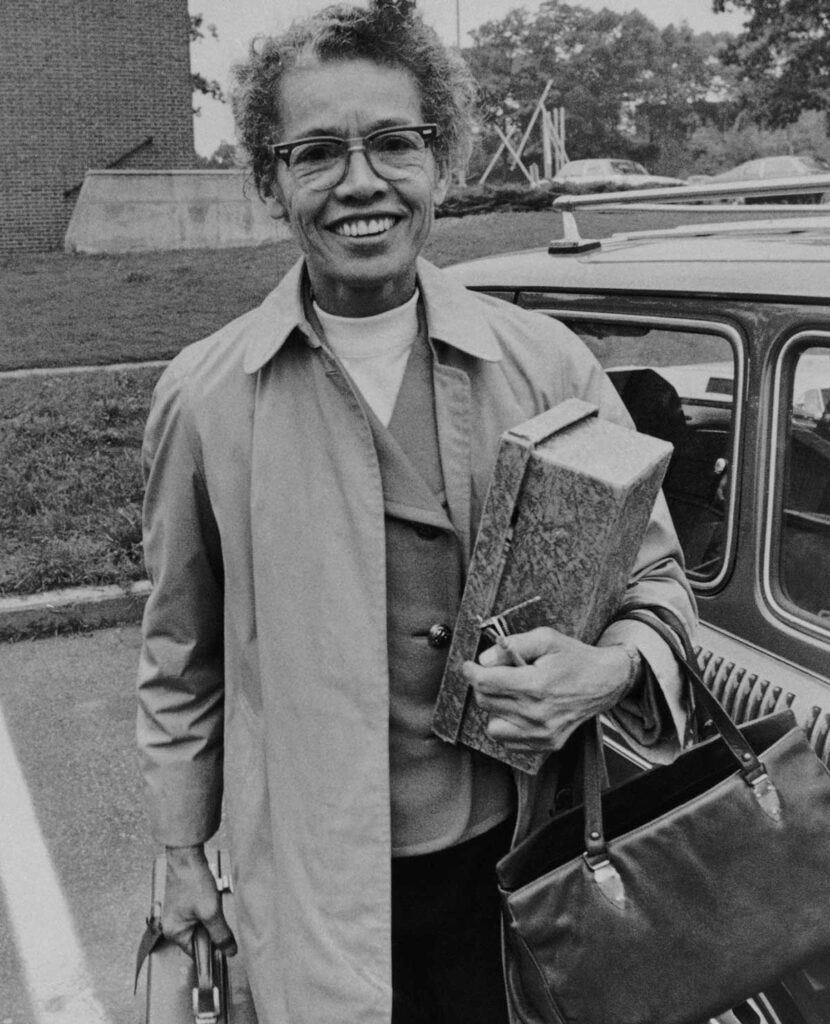

“My Name Is Pauli Murray,” out October 1 on Amazon Prime, is Julie Cohen and Betsy West’s illuminating documentary profile of the remarkable, queer, non-binary, human rights activist, lawyer, poet, and reverend. Murray was instrumental in combating race- and gender-based discrimination at a time when there was great risk in doing so. She and a friend refused to move to the back of a bus 15 years before Rosa Parks — they were arrested for their action — and it spurred her interest in fighting for civil rights. When Murray was denied entrance into University of North Carolina because of her race, she wrote to then-President Roosevelt, as well as Eleanor Roosevelt. The latter became a lifelong friend. Murray’s efforts to challenge gender discrimination using the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, was also the basis for Thurgood Marshall’s arguments in Brown v. Board of Education and Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s work. Through fabulous interviews with and recordings by Murray, as well as testimonies by a slew of talking heads, “My Name Is Pauli Murray” shines a necessary light on a woman whose work is essential, and largely unknown, but whose legacy continues today.

Cohen and West spoke with PGN about their documentary and subject.

How did you first learn of Pauli Murray and what approach did you take to the documentary?

Betsy West: We learned about her in the process of doing our “RBG” documentary. Ruth Bader Ginsberg had put Pauli Murray’s name on the cover of the first brief she wrote on gender equality before the Supreme Court. She did this to acknowledge that Pauli came up with a seminal idea that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment could be used to win equality for women. We knew that Pauli Murray was a groundbreaking legal feminist scholar, but not much more than that. We did research and were blown away by her story and that we didn’t know more about this person.

Julie Cohen: Pauli Murray saved an incredible archive of 141 boxes of papers, drafts of legal writings, diary entries, and 800 incredible photos by and of Pauli. We found 40 hours of audio tape and video tape — materials to reconstruct Pauli’s life. Biographers wrote biographies, but we were going in as filmmakers, so that gave primacy to audio and video. The decision about what to include had to do with what the strongest audio and video was — her voice was so strong, the words and timbre of her voice. So, it was what was most provocative and most pushing at your heart.

West: We didn’t want to be presumptuous, frankly, and we wanted as much as possible, to tell the story from Pauli’s point of view and in Pauli’s own words, and we had the materials to do that.

Murray questioned gender and felt she was a “man in a woman’s body.” She took on a masculine appearance during her youth and had romances (only) with women. She sought testosterone treatments. Some interviewees in the film report she kept her sexuality under the radar. Others suggest Murray would have used “they/them” as their pronouns. What observations do you have about Murray’s gender?

West: We have to go back and try to put ourselves in the time of Pauli Murray in 1930s and ‘40s when there really was no language or understanding of gender nonconforming. She was writing to doctors and expressing the feeling that she was a man and suggesting maybe testosterone would help. The doctors were of no help. They were dismissive. She never took this struggle publicly. We’re left with questions. She had a long relationship with a woman that seems to be deeply fulfilling. Many people who knew about or suspected it would consider it to be a lesbian relationship. It’s hard for us now to characterize that. We were also influenced by the idea that Pauli’s struggle with gender helped with her unconventional, innovative thinking. Here’s a person who understood that racial and sexual boundaries are arbitrary. Other scholars have made the point that this really helped her legal thinking — to suggest that arbitrary discrimination on the basis of these things is absolutely wrong.

Murray suffered from depression and had emotional breakdowns. Yet she was incredibly accomplished in many ways. Can you talk about her character? Do you feel that she — like many queer people — overcompensated to find ways of fitting in and finding acceptance?

Cohen: I don’t know that we can answer that. Pauli’s struggles with mental illness are hard to pick apart. She was devastated and depressed because of how she was being dismissed by doctors. When Pauli said, “I am a man, why can’t that be recognized or do something to confirm that?” The doctors would say that made no sense. Of course, she’s depressed. That’s a depressing thing to hear. She had a thyroid condition that was treated later in life, so there is a suggestion that was the core of her struggles. Was Pauli trying to achieve up a story to create acceptance? Possibly. Certainly, later in life she found happiness and peace in a loving ongoing steady partnership with Irene, and through Episcopalian priesthood and retreat in spirituality and the Christian teachings of love and reconciliation and serenity she hadn’t been able to find when she was out there fighting political and activist battles.

How do you process all of her dynamic reinventions?

Cohen: You can interpret Pauli’s stories in a number of ways. She loved being ahead of the curve and planting a flag in a new territory. Was she constantly seeking and searching that led her to veer from one movement to next in a quest to find inner peace? It’s hard to say, but she changed course so many times, she made it difficult to tell her entire life in a single film.

West: Pauli was very adventuresome. She dresses up as a boy and rides the rails during the Great Depression. Similarly, having obtained an amount of stability in a job in New York with a big law firm, decides, “I’m disgusted with a country that is still tolerating lynching, I’m going to move to Africa and take part in independence movement going on there.” She was constantly looking for her next adventure.

Chase Strangio says in the film that Murray “conceptualized the legal architecture for challenging systems of discrimination.” Eleanor Roosevelt tells Murray, “change comes slowly.” Murray was said to be “ahead of her time.” Could we posit, “What if?” Murray had been given the opportunities she was denied. Would that have fomented change sooner?

Cohen: I think if some of the barriers placed in her way had been lifted sooner, she would have possibly been able to make changes faster. We also think she would have gravitated to her professional love of writing. She wanted to be a poet and a writer. But obstacles kept coming up that required activism and legal battles and fights against bigotry. Her development as artist was one of the main things we missed by all her discrimination she faced in her life.