The HIV epidemic is far from over. Local and national efforts to end HIV manifest largely in the form of biomedical treatment and prevention education. One such effort is a large-scale federal government initiative called Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE). EHE programs exist in local governments as well, including Philadelphia. Philly’s EHE method consists of four main tenets: diagnosing, treating, preventing and responding.

But for many LGBTQ+ people of color in Philadelphia, HIV infections are rapidly spiking, according to José de Marco, an organizer for the AIDS activism group ACT UP. “We’re noticing,” de Marco said, “why are infections going up in certain communities and being lowered in our white counterparts – white queer men, their numbers are going down. You start looking at why; no one’s having sex any differently than anyone else is.”

According to the 2019 report HIV in Philadelphia by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, non-Hispanic Black people, people assigned male at birth, men who have sex with men (MSM), and people who are 50 and up comprised the largest percentages of people living with HIV by race/ethnicity, biological sex, transmission risk and age group.

In the case of queer and trans people of color who experience homelessness or incarceration, who struggle with addiction, or rely on survival sex work to sustain themselves, the biomedical method of HIV treatment is not an effective way of mitigating HIV transmission, de Marco said.

“You get a script, take the meds, and you won’t be able to transmit HIV, is what that basically boils down to,” de Marco said. “But that’s with the caveat you can access the medicines and you can consistently take them.”

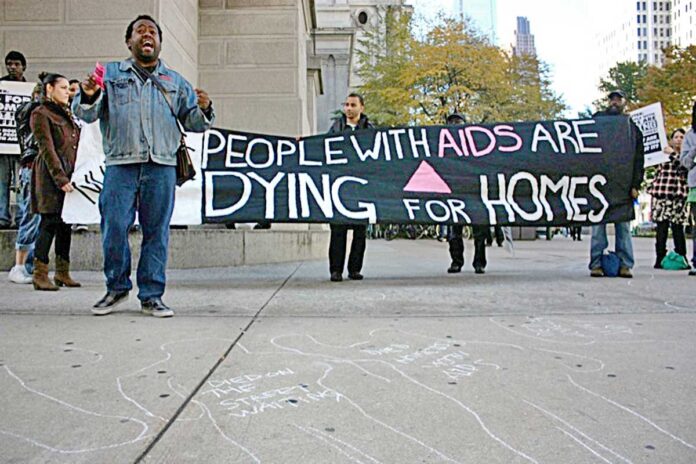

Through ACT UP, de Marco and their fellow activists have been advocating for safe permanent housing for people experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity.

“I believe housing is a common denominator for everything,” de Marco said. “It’s as simple as using the biomedical model, but where are you supposed to store your pills if you’re homeless? You need a safe, clean place for your meds to take them daily, even if it’s no bigger than a single room and a bathroom.”

De Marco said that people experiencing homelessness can get a hold of HIV medication through Medicaid programs, the Special Pharmaceutical Benefits Program and the Ryan White Program. “That’s provided you can identify homeless people who are HIV positive,” they added.

Viviana Ortiz, who works as a community engagement specialist for Prevention Point Philadelphia, also cited lack of adequate housing in Philadelphia as a factor that perpetuates the spread of HIV. She zeroed in on local shelter systems that erect barriers for many queer and trans, Black and indigenous people of color (QTBIPOC) experiencing homelessness.

“I’m speaking collectively about the City’s shelter systems,” Ortiz said. “You stay there tonight, and you’re taking your hormones, you’re HIV positive, you may have other health conditions. You go and they’re going to hold all your medications. But when they kick you out at 5 in the morning, your medications are lost. People know that you get robbed in the shelters, people know you get beat up in the shelters.”

A lack of Spanish-speaking shelter employees is another of many reasons that QTBIPOC experiencing homlessness avoid going to shelters, Ortiz said.

HIV service organizations that are run by white, cisgender people who don’t really know the QTBIPOC community pose another problem. Instead of just testing Black and Brown people for HIV, Ortiz said HIV service providers should be asking “‘do you need to find employment, do you need to go to college, or do you need help with creating a resume.’ Those simple things can make a difference for someone not being infected with HIV because they can find employment versus doing sex work.”

Survival sex work is a common way of keeping a roof over your head in QTBIPOC communities, Ortiz said. Multiple societal factors are to blame for this trend.

“You have two strikes against you in society,” Ortiz said. “You have the color of your skin as a strike, and then you have either your gender identity, how it’s presented and how it’s perceived, and you may have your sexual orientation. Those things close options for folks, [close] access to liveable-wage employment.”

Queer and trans individuals who rely on sex work to live are not always able to demand safe sex. “I know friends of mine who do sex work and the money will be double, triple, quadruble the amount than it would be using a condom,” Ortiz said.

“Not only trans women, but guys on the street do it all the time,” de Marco added.

Ortiz and de Marco talked about the issue of injection drug use, including crystal meth use, that plays a part in perpetuating HIV in QTBIPOC communities. The issue at the core of the problem remains that white people who struggle with drug use often get the treatment they need, while Black and Brown folks are often incarcerated for using drugs.

“Crystal meth is a really big problem for queer men of color,” de Marco said. “Many moons ago, when it was an issue for white queer men that were doing a lot of crystal, there was prevention money from the City Health Department. But right now there’s no money for us.”

Harm reduction is the way to go instead of immediately resorting to treatment centers, de Marco said. “If you want to do crystal, use PrEP. It’s as simple as that.” But even the world of harm reduction has been white-washed.

“A lot of harm reduction [specialists] believe that Black and Brown folks are incapable of doing harm reduction,” Ortiz said. “I’ve heard this in the field from former colleagues.”

Ortiz’s statement is reminiscent of the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis, when many in the medical establishment believed injection drug users should not be considered for clinical trials because they were deemed “unreliable.”

Ortiz added that the messaging surrounding drug use and harm reduction is largely geared toward young, suburban white people using opioids. “On a national platform, there is a drug epidemic, and the drug epidemic is a mental disease if you’re a white person,” Ortiz said. “You had young white kids doing heroin, and Black and Brown folks were getting criminalized.”

Stigma proves a common theme when it comes to all of the social factors that contribute to rising HIV rates. Queer folks are sometimes reluctant to enter a QTBIPOC, HIV service-providing organization like GALAEI because they’re afraid to be associated with an LGBTQ-centric space, said Jorian Rivera-Veintidos, prevention manager at GALAEI.

“We like to go with the narrative that it doesn’t really matter what space you’re going into, what’s important is that you’re worried about the safety of your health, you’re worried about your status, you’re worried about the fact that you had unprotected sex with somebody.”

In other cases, some Black and Brown men struggle to even admit their feelings for another man, de Marco said.

“People who are not able to be out with their sexuality — they live in certain neighborhoods [where] you’re not able to stick a rainbow flag outside your door, so you’re reduced to clandestine lives. For a lot of people living under systemic racism and white supremacy, I think that has an awful lot to do with it for queer men of color.”

While the public messaging around HIV has evolved in recent years to include QTBIPOC to some extent, there is still room for improvement.

“I don’t feel like it’s being discussed as much as it should,” said Nelson Torres-Gomez, prevention specialist at GALAEI. “I think that has to do in part with the stigma behind it. Or the mindset of, ‘it’s not happening to me so it doesn’t matter.’ I think we’re doing good; we have a lot of people that are reaching out. But I think we can do a lot better.”

De Marco founded the organization Black and Latinx Community Control of Health out of ACT UP Philly, a group for QTBIPOC who are most affected by HIV. “We have honest, up-front dialogue with each other,” de Marco said. Ortiz and Rivera-Veintidos are also part of the group.

“The community is coming together and taking back what they feel like is theirs,” Rivera-Veintidos said. “Not so much relying on false information or [nihilistic] ways of healing, when we can honestly take those trials and tribulations ourselves and form it into a narrative of — this is what we need, this is what we want, this is how we have to get it.”

Members of Black and Latinx Community Control of Health have been meeting with Philadelphia Department of Public Health employees and making suggestions, including directing funding to smaller, Black and Brown-led HIV service organizations. “I think [Health Department] is actually hearing us,” de Marco said. “When this EHE money became available I said, ‘wait a minute, this money should not go to these large organizations again, it has to come to communities that are serving us. I think they’re realizing that what’s been going on in the past in Philadelphia has not been working.”

In order to bust some of the barriers to treatment and prevention for QTBIPOC, Ortiz said that people working in HIV service organizations have to understand and support the entire, intersectional identities of those people.

“You cannot just [hire] queer people because they’re queer, but you’re missing the racial component of it,” Ortiz said. “You may put a queer person of color in there, but now you’re missing possibly the educational component — that person may have access to education and can’t communicate with folks that don’t have academic credentials, or understand the struggles of a Black or Brown queer person that’s in poverty. In order to make that change you have to be clear and intentional of who you’re putting in these positions.”