It wasn’t until 2003 that the Olympics had a formal policy for trans participants, requiring gender confirmation surgeries including the removals of the gonads and change to external genitalia, as well as legal recognition of their gender and two years or so of hormonal treatment.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there were no trans Olympians.

These policies were changed in 2015, to ease the legal and surgical requirements. While they moved to allowing transgender people to declare their gender, they did include a requirement that a transgender person have less than 10 nanomoles per liter of testosterone in their system. I’m not wholly sure how that might apply to trans men or non-binary Olympians.

Those rules were finalized in time for the 2016 Olympics, in which zero transgender people participated.

While the Olympics has not further augmented their policies, the involvement of World Athletics has cast a shadow on the games by their own policies, changing the testosterone limit on transgender athletes to 5 nanomoles per liter, in line with their policies on Semenya and other intersexed athletes.

It’s important to understand that, in spite of what one’s 5th grade biology textbook may have led you to believe, both those assigned male and those assigned female have testosterone in their system. The hormone is believed to aid performance, leading to questions about female-identified athletes with what some may consider an overabundance of it occurring in their system.

As a result, World Athletics has reacted to all this by banning athletes from competing unless they agree to artificially lower their testosterone through medication or surgical intervention.

As most athletes need to perform in competitions under World Athletics rules to qualify for the Olympics, this may as well be viewed as part of the Olympics policies.

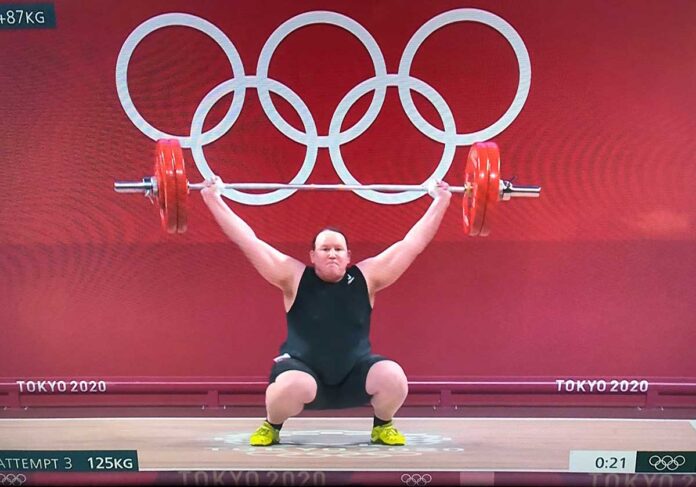

At the Tokyo Games, we finally saw the first transgender and non-binary identified Olympians, even as so many non-transgender athletes were being barred from their sports. Quinn won gold as part of the Canadian soccer team, while Alana Smith — a non-binary skateboarder — and Laurel Hubbard — a transfeminine weightlifter competed but did not medal.

You would assume, from listening to a lot of the popular media, that there is a mass movement for male athletes to flout such rules and force themselves into women’s sports. Certainly, I’ve seen plenty of pundits and others claiming that such sporting events are under threat from the supposedly naturally superior men dominating women’s sports.

Yet at the premiere sporting event in the world, this didn’t seem to happen. Indeed, you will be hard-pressed to find any trans or non-binary identified athletes dominating their sports. I’d wish them well, but they remain few and far between.

Rather, you see policies created out of this fear mongering affecting intersexed people and others: Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi from Namibia and Francine Niyonsaba of Burundi.

Each of these runners faced issues over their testosterone levels, a controversy that started over South Africa’s Caster Semenya who had hoped to defend her own Olympics wins in Tokyo, only to be halted over the amount of naturally-occurring testosterone in her system.

Niyonsaba, the second-highest ranking 800m runner in the world, faced the same choices as the highest-ranked Semenya: medical intervention, participating in a men’s race, or opting to race in something other than the 800m. She chose the latter of those three, eventually being disqualified in Tokyo over a technicality that didn’t seemingly involve her Body’s chemistry.

Likewise, Masilingi and Mboma were barred from the 400m sprint under the same rules. They instead opted for the 200m sprint, where Mboma finished second.

I feel it important to note, before anyone asks, that none of the above athletes are transgender women.

Oh, and one final note on Mboma. After her silver-medal win at Tokyo, a former athlete, Poland’s Marcin Urbas, demanded she be forced to prove she’s a woman. “I would like to request a thorough test on Mboma to find out if she definitely is a woman.”

Urbas made no such claim about the gold medalist, Elaine Thompson-Herah of Jamaica.

World Athletics — like any anti-trans bigot — would argue that such policies are necessary to protect womens’ sports. We simply cannot let anyone who doesn’t fit their narrowly defined parameters to participate, they’d argue, demanding that these athletes consider surgical intervention to alter their body in some way that they’d see fit.

Even then, Marcin Urbas might want a panty check, just to make sure.

Michael Phelps, a swimmer who took home a staggering 23 Olympic gold medals in his career, has a number of advantages over his opponents. His wingspan is large, and his angles are double jointed. He also doesn’t produce fatigue-inducing lactic acid. Yet no one is telling him he needs to change his physiology to participate — they’re just lauding him as they hand him medal over medal.

But under the threat — expressed or implied — of male athletes taking advantage of only-recently implemented trans policies, predominantly African female athletes are finding themselves barred from competing due to a potential natural advantage of their own.

I hope, should the Olympics themselves even continue, that I’ll see more transgender people complete. I hope those that do take home medals, too.

Yet I find myself more than worried that any policies that may just barely allow our participation will simply be used to bar others from having a chance — and that’s just not right.

Gwen Smith feels this was but one of many controversies this Olympics. You’ll find her at www.gwensmith.com/.