On July 10th, 1981, PGN ran its first article about “a rare and fatal form of cancer” with 41 known cases in New York and California. Physicians were unable to diagnose the illness, making it hard to track how many people had been affected. The illness went through many names — some more upsetting and discriminatory than others: GRID (gay-related immune deficiency), CAID (community-acquired immune deficiency), ACID (acquired immune-deficiency), “gay plague” as used by some mainstream publications including The Philadelphia Inquirer, and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). In the years and decades that followed, PGN ran so many articles and features on HIV/AIDS that it earned the nickname Philadelphia AIDS News.

40 years after it was first reported in the media, AIDS-related complications have killed 34 million people globally and 700-thousand in the United States, and there are currently 37 million people living with HIV worldwide, including 1.2 million in the United States. Despite the advance in treatments and prevention (including PrEP and PEP), tens of thousands of new cases of HIV are reported in the U.S. each year, including 37-thousand in 2018, with some groups much more at risk than others.

Even though the media and the medical community have had four decades to educate the public about HIV/AIDS, many myths remain about the illness that continues to devastate communities around the world. It remains the job of the media, especially local LGBTQ media, to put out the latest and most accurate information and to debunk falsities surrounding HIV/AIDS.

To start, this year is not the 40th anniversary of HIV/AIDS. It’s the 40th anniversary since the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States. HIV/AIDS arrived in the U.S. as early as the 1940s or 50s, and it had been spreading on other continents in the decades before that. It was only in 1981 that enough people were infected that the media took notice.

Many of the most vulnerable groups in the 1980s remain the most vulnerable groups today. While white gay men were largely the face of the epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s, HIV/AIDS affected, and continues to affect, other groups of people, often much more significantly. In 2021, trans people of color, people experiencing homelessness, and Black gay and bisexual men are all at heighted risk for HIV infection. A recent CDC report of trans women in seven major cities revealed that 42% of those surveyed were HIV-positive, including 51% of trans women surveyed in Philadelphia. And a 2020 report from the city of Philadelphia revealed that Black msm accounted for over a third of the people diagnosed with HIV in 2019. That same report revealed people living with HIV (PLWH) experiencing homelessness were 53% less likely to receive antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Although treatments like ART are available, they can be inaccessible for many. Although the advance in treatment options, including protease inhibitors in 1996 helped some groups, many populations remain at risk, especially those with high rates of people without health insurance. The only time the cost of an HIV/AIDS drug was lowered in the U.S. was AZT in September 1989, and despite programs to help people afford HIV/AIDS treatments, there still remains a disparity between people diagnosed with HIV and those who are virally suppressed. According to the CDC, in 2018, only 56 out of 100 adults and adolescents with HIV were virally suppressed.

Moreover, treatment and prevention options don’t help people who don’t know their status. The city of Philadelphia estimated that 1,700 people living with HIV do not know their status, and those people made up approximately 39% of new infections in 2018. Nationally, of the 1.2 million PLWH, about 240-thousand people don’t know they are HIV positive.

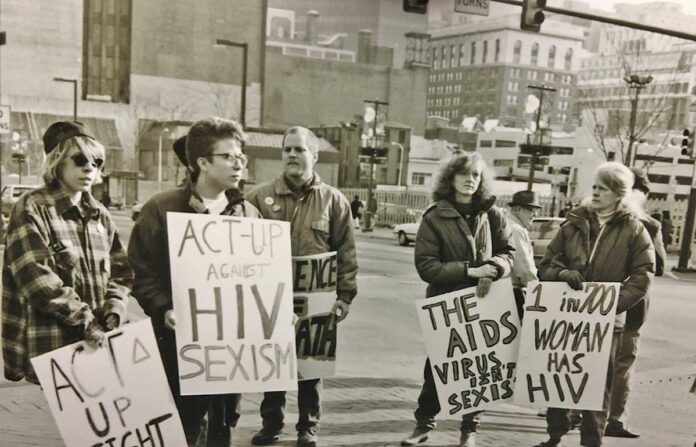

HIV/AIDS continues to highlight inequality among populations. Up until August, 1991, it was difficult for women to be officially diagnosed with AIDS because the CDC definition did not account for the different epidemiologic patterns between women and men. It was also difficult for women to get involved in clinical trials for HIV/AIDS treatments or treatments for opportunistic infections. In 2019, a CDC report revealed that although HIV infections in women have declined in the past ten years, rates among Black women are higher than white women. The report found that “Reducing racial disparities among women is needed to achieve broader HIV control goals. Addressing social and structural determinants of health and applying tailored strategies to reduce HIV incidence in black women and their partners are important elements to achieving health equity.”

Times have changed, but the urgency remains. In the 1980s and 90s, oftentimes 75 percent of PGN’s news stories were about HIV/AIDS. The reports and editorials in PGN, urging people to remain hopeful while also alerting them to the interference of politics and religion, shed light on an uncertain time for many. And although a lot has been learned in 40 years, that work of education continues today.