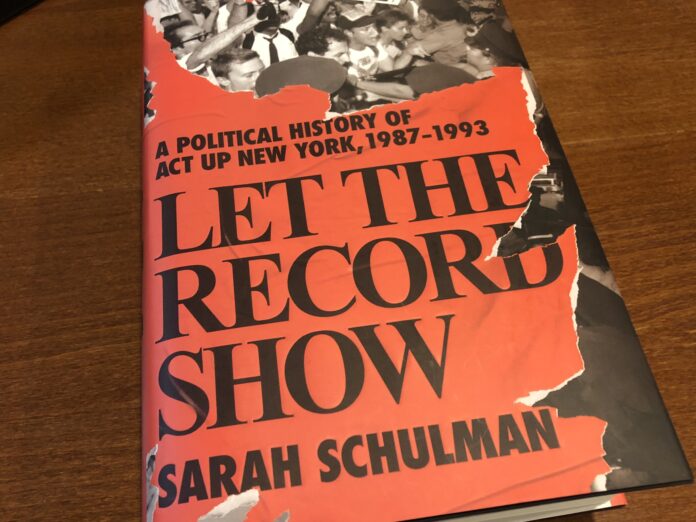

In Sarah Schulman’s new book, “Let The Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993,” she says about ACT UP members: “These were the people least likely to make substantive change, participating in the broadest possible coalition, most of whom, in some or all aspects of their lives, were excluded from basic rights… They created complex social services, tried to change public representation, and impacted how bureaucracies function so that a more truthful story could be told that supported and helped a wider range of people.”

The story of ACT UP and its various chapters, specifically ACT UP New York, can’t be told swiftly (Schulman’s book is an important part of that story, and it comes in at 700 pages), but some of the lessons gleaned from it — about activism, about changing entrenched and unfair systems, about the complexity of group dynamics and interpersonal relationships — should be shared as widely as possible, not only to aid those currently fighting other forms of injustice, but to remind people that the HIV/AIDS crisis is not over. Not for those still grappling with the utter trauma from the ‘80s and ‘90s, and not for those dealing with the less-than-rosy reality of 2021.

It is unwise to compare the HIV/AIDS crisis to any other point in history, including the COVID pandemic. While some of the government players may be the same and while some of the methods to reduce spread may overlap, the HIV/AIDS crisis before protease inhibitors was, as one activist put it, a “private hell” for those affected. There was no government help, the mainstream media parroted incorrect information, the pharmaceutical industry focused on profits instead of patients, and cultural monuments like the Catholic Church did their best to ensure people kept dying.

So, how did ACT UP members force such a seemingly impermeable system to change?

For one, they took on each roadblock individually by focusing on specific targets. To get the government to pay attention, they focused on the Food and Drug Administration headquarters rather than the White House, since the FDA directly handled the approval process for new medications and treatments. To get the media to start reporting fairly, they focused on educating individual reporters, especially those at influential outlets like the New York Times. And they went inside the church where Cardinal John O’Connor was giving mass on Sunday morning, to directly address the man in a place where he couldn’t turn a blind eye.

ACT UP recognized the importance of having members who could communicate openly with government officials, the media, and the medical establishment, but the group also understood the importance of having members who could perform (in every sense of the word) actions like Stop The Church that would truly get the public’s attention. And sometimes it was the same people who did both things. The group had conceptualizers who were able to see connections and chart a course, and the group had implementers who were able to make the vision possible.

Also important was that ACT UP allowed members the freedom to work in a way that best suited their talents, as well as the freedom for members to suggest actions and have them be approved without a long, drawn-out process. There simply wasn’t time for bureaucracy. There simply wasn’t time to let things digest. ACT UP members came from a variety of backgrounds and experiences, and the diversity of the membership contributed to the creativity that helped find potential solutions and to the expertise that helped set them into motion. People brought their unique selves to the table, and they came together with others in support of a shared goal: direct action to end the AIDS crisis. And meetings were in the NYC Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, a place that people trusted and felt comfortable to be in.

All of those things — a diverse membership, unity over a shared goal, using time wisely, and having a meaningful meeting space — are points that activists in 2021 can use in their efforts.

If you’re interested in learning more, Sarah Schulman’s book is a good place to start. You can also watch a virtual conversation between Schulman and myself on June 29th, hosted by the Free Library. For more information on that, visit www.freelibrary.org/.